In the sixteenth and seventeenth century there were many stories taken as evidence of St Thomas’ travelling and preaching in South America. Indians were said to have told the Spanish invaders of tall white men who had visited them previously, and shown them the footprints they left in rocks, in Brazil, Paraguay, Quito and Chile.

One of the Spanish who was curious about the indigenous history, and particularly the signs and stories of St Thomas, was Antonia de la Calancha, an Augustinian monk. There are some interesting insights in his writings, though almost submerged by obsequious praise of his wise and moral superiors and predecessors, which tells us much about the hierarchical nature of his order, and stories of the miracles worked in the New World, which reveals the level of superstition and credulity in which he lived, there are some special insights into the original Peru that still survived around him. He describes his investigations of Lima and Calango in his Chronicles of the Augustinians of Peru, Book Two Chapter Three, p 327..

“What is now the city of Lima never had a great population, but was inhabited by the indians who looked after the temples, which we now understand to have been very impressive, each with their own buildings, and the greatest shrine and court was that at Pachacamac.

“Along the coast past Pachacamac, travelling towards Pisco and Ica, we reach a place where there is still today the living memory and signs of St Thomas in Calango. Some authors had written of footprints and letters on a stone, but only a little, and not everything. So I took great care, to seek out the opinions of older people of reputation.

“And I was most fortunate to discover Father Jan Vasquez, who is now Rector of the village of Santiago on the outskirts of Lima, a wise linguist and a great Preacher of the indians. This was in the year 1570 when he had already gained great merits and reputation.

“This spiritual man has questioned several times different indians of Calango, and they all told his the same story. In ancient times, a man came through these valleys and lands, white, tall and bearded. He preached a law to teach them the road to heaven and prohibit the vices that lead people to hell. They must stop their drunkenness, adultery and sleeping with many women.

“He rested one night on a stone in the valley above, and left there the imprint of his whole body, from his head to his calves.

“In the town he made a print of his left foot on a rock, and wrote some letters in the rock with his finger. The print of the other foot is on another great rock by a bend in the river, where he was preaching to the crowds, to teach them that they had been talking with God. This is what Father Juan Vasquez told me.

“And I met a religious of the Order of Santo Domingo who had been a doctrinante in Calango for many years. He had studied their history and traditions, and this is what he told me.

“Calango was once a large town, and now there are just fifty tax paying indians. They were always very pagan, and still today are not very catholic.”

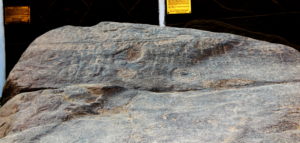

“There is a great rock more than twelve feet long next to the old church. It is white, smooth and polished, unlike other rocks, so that when the sun or moon shines on it, it seems to be made of silver. There is a footprint as if impressed in soft wax, and above a line of letters.

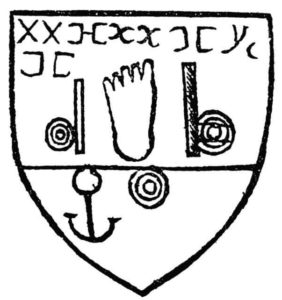

“I painted the marks of the letters, and made a stamp of them onto a paper, and sent it round the convents of Lima. All agreed that it was greek or hebrew, but they could not read it.”

“The indians took me twelve blocks from town to a plain in the valley above, where they sow coca. Here, they showed me on a flat rock the appearance of a large body that is wrapped in a shroud, for it has its feet together, and I saw the heels, the calves and the thighs, the elbows neck and head. “

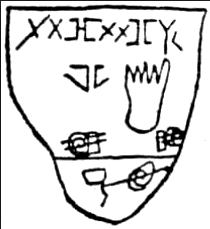

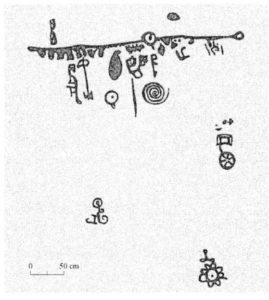

The age of reason brought the scientific rigour that is required to produce the above record of the Calango stone, done by university students. The two sketches below were done by the intellectual elite of seventeenth century Spain, members of the catholic church, who had already decided they were looking at the footprint of St Thomas, keys representing a metaphor about the church, and Hebrew script. Something similar happens with twitter today.

“The indians told me that a tall white man had come, and slept one night on the flat stone. He placed his foot on the stone in the town, and left his other footprint across the river, as he was leaving for faraway places. He wrote with his finger on the rock, to show to them that his god was powerful, and his law was true. The people greatly valued these three rocks, and built shelters of branches over them, out of respect.

“In the year 1525 the Licenciado Duarte Fernandez, a Doctor in Rights and a great lawyer for the church, very knowledgeable, was sent from Lima as an inspector by Archbishop Gonzalo de Ocampo, to destroy the letters. I could not believe something so bad.” This is what the Padre told me.

“So I myself decided to visit, as I was still fifteen leagues from Lima, but just two from Calango. And as the letters were already removed, and the footprint, the memory of this antiquity would also be lost, and the traces of the great and holy St Thomas.

“We entered the valley through bare hills, with cane fields, and dismounted to cross the ford. The village in its entirety worships idols, and the priests of the huacas and the masters of witchcraft all live here. Some of the locals have blue faces. There are many fruits growing on the trees, and tasty fish in the river. Francisco de Avila, it is said, visited here in 1611, and discovered a temple which he destroyed. He erected 37 crosses over 37 of their shrines, and wrote its name in the book of visits.

“…i en la legua materna se llamava entre los de la parcialidad yumisca lantacaura, qu significa la vestiduro o pellejo de la estrella…”

“The chief told me, that the stone is called Coyllur Sayana, the Stone where the Star Stopped, in General Quechua, or Zlumisca Lantacaura, the skin of the star, in the people’s own language. Two lovers were resting on the stone, and looking at the sky, when a star fell down, and confused them.

“When Duarte Fernandez came, he saw that all around the stone, were little underground niches housing burials, some very recent, and so he chopped at the stone and put up a cross at the head of the stone. He wanted to stop the superstition, but it was not well done. Perhaps he was inspired by heaven. The other rocks are still there today, across the river.”

A modern interpretation of the the word Calango looks to the Aymara words kalacango, kala-canco or covered stone. There is a hamlet nearby called Aymares, and the church in Calango is dedicated to the Virgen de la Candelaria, a cult with hundreds of thousands of followers who celebrate a February festival in Arequipa, Puno and Bolivia, the heartland of the Aymara speaking pastoral people, alpaca herders in the altiplano, the high cold Andes. Could “Zumisca lantacaura”, which Antonio de la Calancha tells us is “the people’s own language”, also be Aymara?

In the Aymara spoken around southern Peru and northern Bolivia, star is warawara. But there is another branch of the language called Central Aymara, which is almost extinct. It survives as Jaqaru, which is now spoken in only one community. The village of Tupe and its surrounds, at 2840 metres above sea level, has a population of a little over six hundred. Just a few dozen elders speak the language fully.

In 2013 this little island of cultural memory was declared a National Heritage Site by Peru`s Congress. The grandmothers have been recruited to teach the basics of their language to the youngsters in their schools. The people are celebrated for maintaining their traditional costume of red and black checkered cloth held on with two large silver pins, tupus. The town is six hours walk on a difficult track from the nearest bus route, or two and a half hours from the nearest point accessible by vehicle.

Tupe is far from the Aymara heartlands of Puno and Bolivia. The Aymara heartlands are hundreds of kilometres to the south. Some suggest that the Yauyos was the centre from where the language spread across the Andes, and is now the last surviving remnant in the north. The settlement is in Yauyos, the highlands close to Paria Caca, the source of the waters that flow to the sea down the Mala, Omas and Cañete valleys. To get close I would have to travel three hours up the river from Cañete to Cotahuasi, and then hitch and walk.

Illustrations from top. Duarte Fernandez’ (probably) sketch of the marking on the Calango stone 1625, Antonio de la Calancha’s sketch as published in his Chronicles 1639, the Calango stone 2016, Jimenez’s sketch of the markings, circa 1980, and the head of the stone, 2016. Together they demonstrate the ability to record data accurately, to distinguish fact from fiction, are relatively modern ideas from the Age of Reason and Age of Enlightenment in Europe, whose concepts are still bitterly opposed in much of the Americas, north and south, where in places the majority of schools are controlled by religious organisations.

Notes: several words and passages in the Huarochiri Manuscript appear to be Aymara or Jaqu, although the Lingua Franca of the manuscript was “General” Quechua.

After saying the star is called Yumisca Lantacaura, a little further on Calancha writes of a “Cantaucaro” at the foot of the stone which is an image of the star. This is a smalller stone, and seems to mean llama’s lassoo or llama’s bridle.

When Francisco de Avila destroyed the shrine of Paria Caca, filling in a well and demolishing standing stones or cairns, the local people with him cry out “ñan Paria Caca huañun!”, which we are told means “Now Paria Caca is dead!” But this is recognisable Quechua, ña being at this time and wuañu- with various suffixes being dead.

In Aymara and Jaqi stone is Qala or Cala. Skin is Lip’ichi, star is wara wara. But there are different names for several stars, the dictionary listed 74 different names for stars and planets.

A comet, or a shooting star for example, was miqala or micala

A long dress could be llumpi or in bolivia, llumi

Llumitha; Arraftrar el veftido

Revising Amerigo`s text, I find that the ll on the first word is also and the second word is a single l.

Different spellings, in the same book, include Llumiska Lumisca, Yumisca, Yimiska Yumiska,

and lautakaura, Lantacaura

“The actual text says” Yumifca Lantacaura q. significa la veftidura o pellejo de eftrella”

In Tupe Jaqi Jaqaru

Yü. La yema del huevo y cualquiera cosa que se le

parece en el color.

Yü jupa. Quinua que tira a amarilla.

Yü laq’a. Tierra amarilla.

Yükiptaña. Pararse de color amarillo, como la yema

Miscala can be table stone Misa Cala or Priests stone (from) Wisa Cala

K’ayra. Rana.

K’ayra wañata. Flaco, chupado.

K’aywiña, amajasiña. Pensar.

Yellows sacred stone red frog?

In Bolivian Quechua, lanti is an idol or graven image, K’ayra is a frog, making lantacaura close to frog idol.

yumay is procreate, anta is copper or red

wara wara is star, wara is baton or staff of office.

but anta wara is the morning star, and anta situwa is the equinox.

wara

so that yumay Kala anta K’ayra would be procreate stone red frog

yumis cala lantaca awa

Awa is cloth in Bolivian Quechua

In