And so I look up Gary Urton, and he is a revelation.

After the sun has set behind the mountains of the sierra, star watchers see a luminous band meandering across the clear night sky. This stream, this river is so bright that it is the dark patches within it which take shape in the imagination.

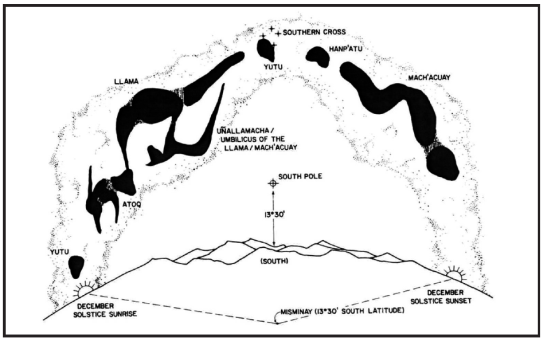

For thousands of years, pastoralists watching over their flocks at night and fishermen returning to the coast before dawn used the skies over the Andes as a timekeeper and direction guide. The figures they see there – llamas, birds, a serpent, a fox – are shadows in the Milky Way.

Villagers in the rural community of Misminay, thirty kilometres from Cusco, shared their concepts of the night sky with archaeologist Gary Upton in the 1980s. His interpretation of their ideas presents a cosmovision linking the night sky with the seasons and, more deeply, with the fertility and order of the Andean world.

The Misminay informants told him of a night sky crossed by a great river, the Mayu. They saw a parallel between the Vilcanota river on earth and the Mayu in the sky, the two running together, one above and one below. The earthly river flows westward in the daytime taking water down to the sea. The celestial river mirrors this, returning water to the heights at night, from where it rains down to irrigate the land. The Vilcanota river is also called the Urubamba, the river of the Sacred Valley, flowing past Cusco towards Machu Picchu. The Mayu is what is known in the West as the Milky Way.

Huarochiri, the highland region where the waters of the Rio Mala have their source, is 450 kilometres from Cusco as the falcon flies, but the narrators of the Huarochiri Manuscript relate a similar interpretation of their skies to that of the villagers of Misminay, above the Sacred Valley.

“They say the Yacana, the animating spirit of llamas, moves through the middle of the sky. We can see it as a black spot. The Yacana moves inside the Milky Way, the River. It is big, really big. It becomes blacker as it approaches through the sky, with two eyes and a very large neck.”

As the Misminay villagers had told Urton, so the Huarochiri narrator relates that the black llama in the arching river of the Milky Way drinks all the water out of the ocean overnight, preventing it from flooding the earth. There is a llama calf suckling on the Yacana, and a small dark spot goes before it, a tinamou, a fat partridge-like bird of the sierra and the selva.

Gary Urton proposed that, whereas in the northern hemisphere people have historically oriented themselves against the east-west plane along which move the sun and the moon, Venus and the other planets, the peoples of the Andes and coastal Peru have looked towards the Mayu, with its north-south orientation, to define their position in the cosmos.

There are further parallels between the seasonal changes in the year, the animals represented by the dark areas in the sky, and the annual cycle of those animals ‘ behaviour patterns – snakes and toads emerging from the ground, foxes mating and giving birth, seasonal birds migrating.

Besides the great llama and its young companion, there are clouds in the celestial river representing a serpent, a toad, a tinamou next to the Southern Cross, a fox, two llamas (for some, a llama and a serpent) and another tinamou.

Besides the great llama and its young companion, there are clouds in the celestial river representing a serpent, a toad, a tinamou next to the Southern Cross, a fox, two llamas (for some, a llama and a serpent) and another tinamou.

On the almost vertical face of one rock at Cochineros, facing the river, there is a group of images, difficult to access, but recorded by Jimenez. He shows a serpent, two tinamous (a plump, almost flightless partridge-like bird), a fox, and two lines of llamas. There is also, below one bird as if it is a scatter of feed corn, a group of seven dots.

This calls to mind Gary Urton’s unpacking of the imagery of the Milky Way. But the relative size and position of the motifs do not match. It is far from a representative map of the Milky Way dark areas. Although the coincidence is intriguing, I am unconvinced.

Gary Urton proposes that for farmers and pastoral shepherds in the Andes, the life cycles of their animals, the progress of the year, and the reading of the suns and the heavens are intimately linked. The snake, for example, is dormant in the Andean cold season from May to July, and then emerges from the earth. The head of the serpent dark shape in the Celestial River appears above the horizon in the first week of August and the body then gradually appears, until the head goes below the horizon in February.

The people of Misminay told Gary Urton that one of their key markers, for seasons and for weather patterns, was the Pleiades. They described a second constellation used as a harvest predictor, a constellation called the Five Stars, Pisqa Coyllur.

This first sighting of the Pleiades, the early Spanish chroniclers wrote, was one of the most important seasonal markers, marked by a festival, the Oncoy Mitta.

In the Huarochiri Manuscript, the Pleiades, Oncoy in Quechua, are said to predict the harvest. “If they come out at their biggest people say “this year we’ll have plenty”. But if they come out at their smallest people say “we’re in for a very hard time.”

The Huarochiri Manuscript tells us that “they call a second constellation, which comes out as a perfect ring, the Pihca Conqui.” This may be the curved tail of the Indo-European constellation Scorpio, which occupies a position opposite the Pleiades. One or the other is nearly always visible in the night sky. These are the same pair of indicators as the Yanesha use as their seasonal guide on the eastern slopes of the Andes.

The Pleiades are visible in the night sky for most of the year, but when they get close to the sun they are no longer seen. In April they are seen in the sky to the south-west, soon after sunset, and they quickly drop below the horizon. Towards the end of April, each year, they disappear. After thirty or forty days, they have moved slightly ahead of the sun and can be seen again, low down on the north-eastern horizon, just before the sun rises.

The Milky Way is a sinuous curve across the heavens. At times it is directly overhead, but four hours later it may have dropped down close to the horizon. During part of the year it runs from north east to south west, and six months later it lies more north west to south east.

At Retama and Cochineros the river runs a few degrees east of north. Standing amongst the stones looking up at the Milky Way twisting above the river, it would be easy to draw a parallel between the flow of earthly waters down to the sea, and its nightly transfer by the Mayu back up to the mountains. Some time in early June, just before dawn, the Pleiades will reappear here, coming over the shoulder of the hillside upriver.

In European northern hemisphere thought and imagery, it is understood that rabbits, eggs, new born lambs, cherry blossom and snowdrops all represent a specific part of the cycle of the solar seasons which is itself deeply symbolic – Passover, Paris in the Spring, mad March hares, Easter. Writers embellish and extend these ideas in poetry and song.

All these interlinked ideas and images are part of western culture. No doubt there was, and is, a similar complex of concepts, links, metaphors and parallels in the Andes. It might be slightly different for llama herders in the high puna, for potato and quinoa farmers in the quechua zone over 2500 metres, for the farmers in the yungas, the warm valleys up to 1500 metres, and for the farmers of the dry desert irrigated by seasonal rivers from the mountains.

In the context of the imagery on Mala rocks, a toad, a serpent, a fox could refer to a season or a related activity. A man leading a group of llamas could refer to activities for festivals when they “raced with their llamas to Paria Caca”. The birds with forked tails could mark the return or departure of swallows or other seasonal birds.

The first sighting of the Pleiades, for example, could be linked with the festival for the goddess Chaupi Ñamca, the annual cleaning of the canals, the reduced flow in the waters of the Rio Mala, the harvesting of certain fruits and the planting of tubers, as well as the mating or giving birth of different birds and animals.