The tupu, a long pin with a broad head used to fasten shawls, has a thousand year history in the Andes, but it is another subject of the Inca Fallacy. In the face of facts, all roads are Inca roads, all metalwork is Inca metalwork, all trapezoidal niches are Inca niches.

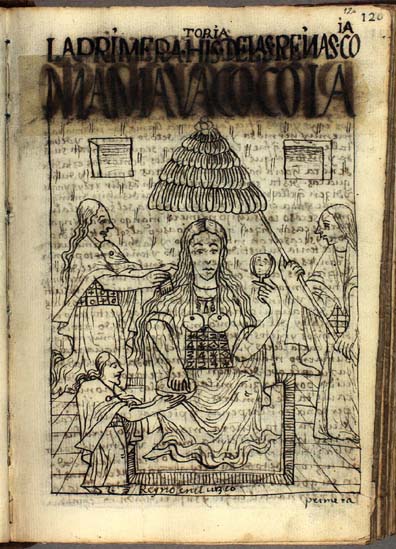

Long pins are seen on the engravings of Guaman Poma de Ayala, a native Peruvian born shortly after the Spanish invasion of the Inca Empire, in his manuscript, Nueva corónica y buen gobierno, completed in 1615, notably in the portrait of  Mama Huaco the first Coya, or wife, of the Inca Yupanqui.

Mama Huaco the first Coya, or wife, of the Inca Yupanqui.

A Guaman Poma drawing of Coya Mama Huaco shows her wearing two round-headed pins, placed with round heads down, with holes positioned between the centre of the head, and the start of the pin.

The accompanying commentary tells us “She was beautiful and dark, of a good height… She could talk to the stones and the rocky hillsides, the Huacas…She wore a rose coloured gown with large tupus of silver…she died in Cusco when she was two hundred years old. ”

This lady was the mother (or sister-wife) of Manco Capac, the first Inca wife. She was the daughter of the sun and the moon, who sowed the first maize, and taught women the art of weaving, which they had already been doing with greater skill than the Inca for 2000 years.

Guaman Pomar translates as Hawk Puma. Two iconic creatures of the Andean cosmovision, suggesting a formidable ancestry. Guaman wrote two amazing books which were rediscovered in 1908 in the Royal Library in Copenhagen, describing in sketches and works the realities of Peru in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century. The book can be viewed online at http://www.kb.dk/permalink/2006/poma/4/es/text/?open=idp39424.

Guaman Poma had an agenda. He was appalled by the barbarism and brutality of the Spanish, and his works were addressed to the Spanish King. It may be that they never reached him. With over 1000 pages and almost 400 drawings the books give us a vivid picture of Inca and Spanish life in the first 70 years after the conquest.

Woman with a single pin placed horizontally with the head to the right are placed in scenes of the Inca hailing the start of the new solar year, planting the first seeds in August, and worshipping at the 400 metre high peak of Wanakari, amongst others. These pins have a variety of designs at the head. Only two of the Queens, the first and the ninth, are shown with tupus in Guaman Poma´s drawings.

We see in his drawings that women inserted large pins, the tupus, into their untailored, wrap-around dresses (acsus) at the chest, just below the shoulders, with the pointed ends facing up, to hold the garment in place. Tupus were worn in pairs, and each pin was connected to its counterpart with a chain or cord. Women used a single smaller pin, called a ttipqui, to secure their mantles (llicllas), which were worn draped across the back and around the shoulders, the ends meeting and overlapping across the chest; the ttipqui was inserted diagonally into the cloth to hold the lliclla in place.

A pair of tumis on the Rock of the Llamas, close by what could be two monkeys on a branch. The tumis as usual are positioned with the pins pointing upwards.

Two tupus on the Rock of the Llamas, centre, with a flower type geometrical design to the left. in the top right there are two more tupus, their round heads having two ornamental circles.

A single tupu lower left) on the Rock of the Llamas, with two in a line leading down a drainage channel from the top surface down towards the riverside face of the rock.

So the Incas wore tupus, but tupus are not Inca. In a cemetery on the edge of present day Lima, the Tablada de Lurin, dating to around 2000 years ago, tupus with round heads pierced by a central hole – just like those on the eastern face of the Pariacaca Rock – were found. These are the earliest dated tupus in Peru, but the style persisted for fifteen hundred years until Inca times, and this is the “classic” tupu style.

In the south central andes, Tiwanuku at the southern tip of lake Titicaca was the centre of a culture, the Wari, that came to dominate the area from 100 to 600 CE, eight hundred years before the Inca became a force. In its later stages people in the bolivian altiplano and further south people mined and smelted ores, produced bronze alloys, and traded metal objects with llama caravans amongst both the highland and coastal communities.

In the Wari adminstrative centre of Pikillacta, close to Cusco, 50 metal objects were found in excavations in 1989. Of 30 which were analysed for metallic composition, 26 were made from arsenic bronze. Tupus comprised almost half of all the items found.

The second largest Wari urban centre at Conchopata yielded 23 metal artefacts over more than 20 years of investigation to 2005. 19 items were analysed and 16 were made of arsenic bronze. Fourteeen of the objects found were tupus.

28 metal objects were found in excavations at Tenahaha, a Wari settlement in the highlands of south central Peru. 25 were found in tombs and 24 of them were tupus.

The Tenahaha tupus are found in a confused situation, with collective tombs, where burial goods have been moved, removed and replaced – together with the burials – after initial burial. Nevertheless, several paired tupus are identified, and they seem to been buried with women. This association is consistent throughout periods and in the rare event that tupus are associated with male burial it has been suggested that it may indicate the male had feminine characteristics.

The tupus are made of a copper-arsenic alloy and may have been hammered into shape from simple t-shaped blanks -not unlike the t-shaped “tumis” drawn on the rock . The shaft would have been curved round to form the pin, and the head would be founded and then hammered flat to form the round head.

Tupus were not just important to Wari and Tiyanuku society, they formed the majority of metal work in graves, more than knives or mace heads or masks or staffs all put together. They, were clearly, highly symbolic. And they were manufactured in the south and central highlands in copper-arsenic alloy from over 1000 years ago.

A pair of bronze tupus in similar to style to those depicted on the Mala rocks. They are of uncertain provenance like most of the objects bought from tomb raiders now on show in the private Larco Museum in Lima.

They were also important elements in Chancay. The Chancay culture flourished in valleys to the north of Lima, from 1000 AD till the coming of the Incas 450 years later. Pairs of tupus are formed modelled on Chancay ceramics, placed below the shoulders, the pins pointing upwards.

These tupus, like those of the Inca, are associated with women, not just in ceramics but in burials. There is such a tupu ascribed to the Chancay people in the Ancon museum just north of Lima.

They were exceptional weavers, and many of their fabrics are preserved in Museo Amano in Lima. Their pottery was also individualistic with black on white patterns symbolising the irrigation of land with lines and zigzag patterns.

High up on the hidden face of Piedra 11, looking down on the river, is a pair of tupus, heads upwards.

On the upper surface of Piedra 1, faint, close by an equally faint pair of monkeys climbing a tree, are two tupus, close by, parallel, a pair . Two more, no four more, two pairs sit close by next to a flower amidst much fine, meandering, indecipherable lines. What identifies them amongst scrawls is the stem, the round head, and two round dots above. These are not just tupus but a particular design of tupu. The same design.

Two more sit below another wheel or flower, with a central hub, again with the distinctive dots. Perhaps one tupu head is a little more heart shaped than round.

Facing south on the main panel of Piedra 11, three tupus, their heads below their pins, with twin curling adornments. On the opposite, hidden face of Piedra 11, two round headed tupus, heads down.

Whilst tupus have a variety of styles, those shown on the rocks of Cochineros all share one style. Unlike the T-objects, which come in different shapes and sizes, point in different directions and are often drawn carelessly, the tupus are all the same dimensions, with the same twin adornments on the round head, and are drawn head downwards or on the flat.

If they are simply symbolic of a metalworkers wares, they are surprisingly uniform.

Another possibility is that, like modern day graffiti, they are the tag-line of a specific group – perhaps women, giving that tupus appear from their appearance in grave goods to be specifically a female and high status adornment – whose symbol is not just a tupu, but a particular tupu design.

Most interesting for the two tupus on the hidden face of the Piedra Pariacaca is that they have a clearly marked hole in the round head, between the centre and the top of the shaft, in exactly the same place as the so-called “classic” archaeological tupu. There can be no doubt here of the identification of the image.

Tupus continued to be used as decoration in colonial times, by the indigenous people and by mestizos, the descendants of the spanish and the native indians. If there is some hidden meaning in the pairing or the directions or the designs of the tupus, perhaps there is still some corner of Peru where these traditions may be maintained?

As it happens, there is a small community where the older people still speak Jaquaru, one of the original root languages on which Quechua is based. These people wear a distinctive costume of black and red, though more often than not of imported fabric rather than home weave today. And they wear giant twin tupus of silver as large as those worn by Mana Huaco Coya, the first Inca queen in Guaman Poma´s sketches of 1615.

There are little more than 500 Jaqaru, whose name means something like Jaqa -people – Aru – that talk. They live in rural communities in the district of Catahuasi, in the remote region of Yauyos that is now a National Reserve. The people, the language itself was declared part of the National Cultural Heritage in 2013.

The Huarochiri Manuscript describes the customs and the conflicts of the Yauyos, and the Yunga, including the Yauyos expansion down from the heights into the valleys. It just so happens that these unique people who maintain the traditional use of tupus are neighbours, sometime enemies and sometime allies, of the people that worked the fields round the stones of Cochineros. Yauyos and Catahuasi is just a few hours upriver from Mala. It would be interesting to see whether they can provide any insight to these paired ornaments inscribed on the rocks hundreds of years ago.