The waiter brings two glasses of cold beer and a couple of pinkish trotters, and we are quiet for a while as we suck on the knuckle bones and wash down the vinegary juices. Then I push the plate of pickled pigs’ feet to one side and open my laptop, pulling up a photograph showing the first rock panel we encountered, on the terrace of apple trees above the patio by the river.

“There are images of different brightness on some rock panels, and the brighter images tend to overlay the darker. They could be fading with time. So I asked myself, can we measure this consistently, and does that measure relate to anything meaningful? You can see the bright heart, the line of dots, the shawl pins…”

“The tupus…” corrects Mayra.

“and behind those is a four legged beast that could be a llama.”

“An indeterminate quadruped.”

“If you prefer. But our eyes and brain interpret these grey tones in a non-linear way – I need a precise measure of the light reflecting off the stone.”

I open another image on the screen.

“Do you see images of different brightness there?”

Mayra looks at the screen, and tilts it a little.

“I would say by eye that these animals running in a line across the rock are brighter.”

There are six long-necked creatures all facing from right to left, five at a similar level on the middle of the panel, and one lower down. Two in the centre have two-toed feet, high curved tails, and delicate heads with two pointed ears. One on the left has no legs, though the body and head are well drawn, whilst that on the far right appears to have a neck but no head or ears.

“And they have clearly been drawn on top of the other images.”

“The tumis and the birds also look fresh.” She points at a small figure. “That stylised bird is characteristic of Chimu ceramics and textiles. There is a feathered tunic in the Amano Museum in Lima with a similar design.”

“Could that give us a date or a cultural link for that image?”

“It might offer us an age range and a link, but not a date. The Chimu came to control much of the coast. The Chancay, just north of Lima, had the same bird in their woven textiles. It was common over a period of five hundred years.”

“That’s a shame. But you agree we have different levels of brightness. I measured grey levels directly from the digital photograph, using image analysis software developed for health research.”

“And what do you find?”

“What you suspect – the five running dogs all have a similar brightness, so they may have been drawn at the same time. The tumis, again, have a similar brightness, so most likely they were also drawn together, but more recently. The background designs form a third, older group.”

“It doesn’t tell us a great deal.”

“We could have hazarded that they were three groups on stylistic grounds. The measurements support that. But I was just practising on this rock. Look at the next one.”

I pulled up another image, of a peaked rock with a steeply slopimg face, above a sudden drop to the river. Our first panel.

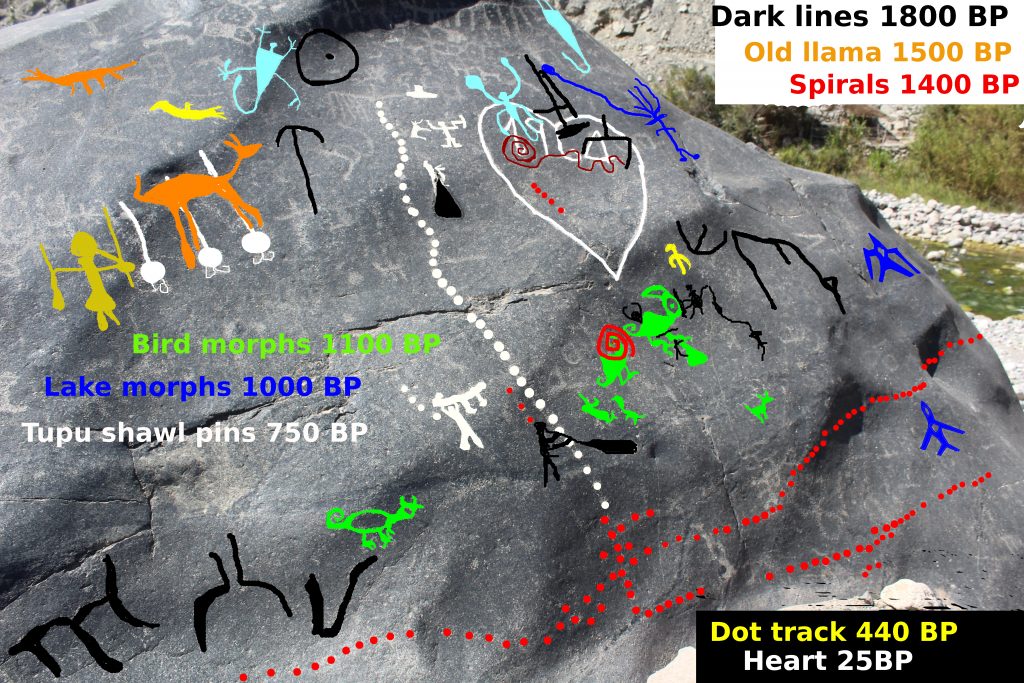

“That is an incredibly data rich panel!” Mayra exclaims. “There are thirty or forty different drawings here, and by eye alone, I can see four brightness levels. I never realised all that when we first saw it.”

“We were squinting at the rock in bright sunlight. The eye can’t handle that, but the camera can. I followed the same process, but put in our calibrating ages – twenty-five years for the heart, and four hundred and forty years for the dot track, the last addition before the spanish destroyed the indigenous society.”

“And what do you get?”

“I can measure the grey levels for five, maybe six different time periods. The decrease in brightness from heart to the llama is four or five times the decrease from heart to the dot track, which I assume represents 415 years. So if the relationship between age and brightness is linear, the drawings would cover a period of sixteen hundred to two thousand years.”

I open another image on the screen. “I put a rough illustration together showing the estimated ages of different images. It is garish, I know.”

“Guffroy suggested the Tradition B on the central coast might go back as far as 2300 BP. So that is about right.”

“Yes, his Tradition B ran from 2300 to 11oo years BP, with naturalist figures…”

“Like the fluid running llamas with four legs….”

“And these were often associated with little cupules…”

“There were two parallel lines of eight cupules on Junior’s rock by the roadside, and a few more on the top of Piedra 6…”

“And then there was a tradition C, with more figurative images used repetitively, from 1000 to 1500 BP”

“Which would fit with our llama trains and tumis!”

“If I am right, that means we have a site spanning the two Traditions. Not just at the same site but on the same panels. And we can relatively date them!”

“Has that been done anywhere else?” asks Mayra.

“Not that I know of. There are sites that span a long time range. But most sites have many smaller stones, rather than the giant panels here. If I use raw images rather than jpegs processed by the camera, and take pictures under controlled conditions, maybe with a flash and no direct sunlight, I think I can narrow the dating down even further.”

“What about my tumis, are they images drawn in 1750 by the Huarochiri rebels moving down the valley?”

“There are no tumis on this panel, so I need to find another approach for that. But what can you tell me about the shawl pins?”

“The tupus! Now they are interesting…”

**********************************************

“Lets take a walk,” Mayra says.

We stroll around the square past the Iglesia de la Familia and head down St Martin with its giant ficus trees, as she gives me a brief history of tupus.

“There is a sixteenth century line drawing by Guaman Poma of the first wife of Inca Yupanqui, showing her wearing two round headed pins, below her shoulders, holding her shawl.”

“So tupus were Inca?”

“No. That’s a classic form of the Inca Fallacy. The Incas built roads – so all roads are Inca. They used the skills of the people they conquered – metalworkers from Chimu, stone masons from Jauja. The greatest talents of the Inca themselves were management and marketing.”

“It got them a long way.”

“They imposed a degree of conformity and standardisation, so the creativity in textiles and ceramics actually declined. And although the Incas wore tupus, tupus are not Inca. Chancay ceramics show human figures wearing pairs of tupus five hundred years before the Inca.”

“These are the same Chancay to the north of Lima that used that bird motif in their textiles.”

“Yes. And the Wari also used tupus. They came from the southern highlands a thousand years before the Inca, and spread their culture across much of Peru. Excavations at three of their major settlements found 101 metal objects, mostly made of arsenic bronze.”

“That is not a lot of metalwork.”

“No. Remember that the Spanish are said to have taken some ten tonnes of gold work and seventy tonnes of silver from the Inca, melted it down and sent it back to Spain. But of those 101 pieces of Wari metalwork, 62 were tupus.”

“So they must have been very important to them.”

“They were mostly buried with women as grave goods. There were more tupus than all the staffs, mace heads, masks or knives put together. The tupus were buried in pairs.”

“The tupus I saw drawn on the rocks were also in pairs.”

“Most of them. When I mapped them I found one triplet, nine pairs, and three solitaries.”

We pass Mario Testino’s museum, a beautifully renovated nineteenth century Barranco building on whose walls hang giant photographs of Lady Diana, Cusco traditional dancers with white masks and wide brimmed hats, and Naomi Campbell. There are several blocks of flats in dull concrete. And then through white painted iron railings appears a neat Italianate villa set amongst lawns, with two giant trees dominating the foreground.

“Pedro de Osma Museum,” Mayra says with pride. “It was a family home, and Pedro was an art collector.”

We walk up a pathway past white marble statues on plinths, to an ornate staircase leading to the open front door.

A central hallway passes rooms filled with sixteenth and seventeenth century paintings, cabinets, silverware, and religious art. We go straight through to emerge facing a longer, larger garden, with an avenue of palm trees. Hummingbirds dash amongst the flowers. We are facing another magnificent white European style mansion.

“We can see the colonial art later,” explains Mayra, “but I want to show you something older.”

At the end of the garden behind the second building is a smaller room with archaeological finds in glass cases. There are large Inca aryballos, wide bodied ceramic vessels with narrow necks for holding chicha, the ceremonial beer, there are queros, ritual cups for ceremonial toasts, and conopas, stone figures of llamas as offerings, and there are Inca tumis and tupus.

“These square, flat bladed tumis are just like some of those on the stones,” explains Alla. “But as we have seen, there are several styles of tumi drawn there. But the tupus are all shown with a long pin, a circular head and two decorative twirls. Just like these!”

There they were, a flat circular disc attached to a long thin pin three times the length. There was a hole in the disc, not centred but towards the top, and two small spirals of silver decorated the top of the disc.

“They are exactly the same!” I exclaim. “So we can date the drawings!”

“Yes, they are the same. But no, it does not give us a date. The most common tupus have simple undecorated discs but this style, mariposa, butterfly, is also widespread, from Bolivia to Cusco to Ayacucho, and from as much as 2000 years ago.”

“Still, at least we know what we are looking at. If serpents are also streams of water, these images on the rocks are definitely shawl pins.”

“Tupus. We know what the drawings depict, but that does not tell us what they mean. Why did the Wari burials have so many bronze tupus, interred in pairs with women? Why did the Mala valley people draw them on the rocks?”

“It looks like another dead end” I suggest. “One more question to which we can never find an answer.”

“That is the reality of archaeology in Peru,” says Mayra. “So much has been destroyed. Giant pyramids of adobe blocks were being bulldozed in Lima just fifty years ago to make way for housing. Our oldest University – a University! – flattened a pyramid to build a football stadium.”

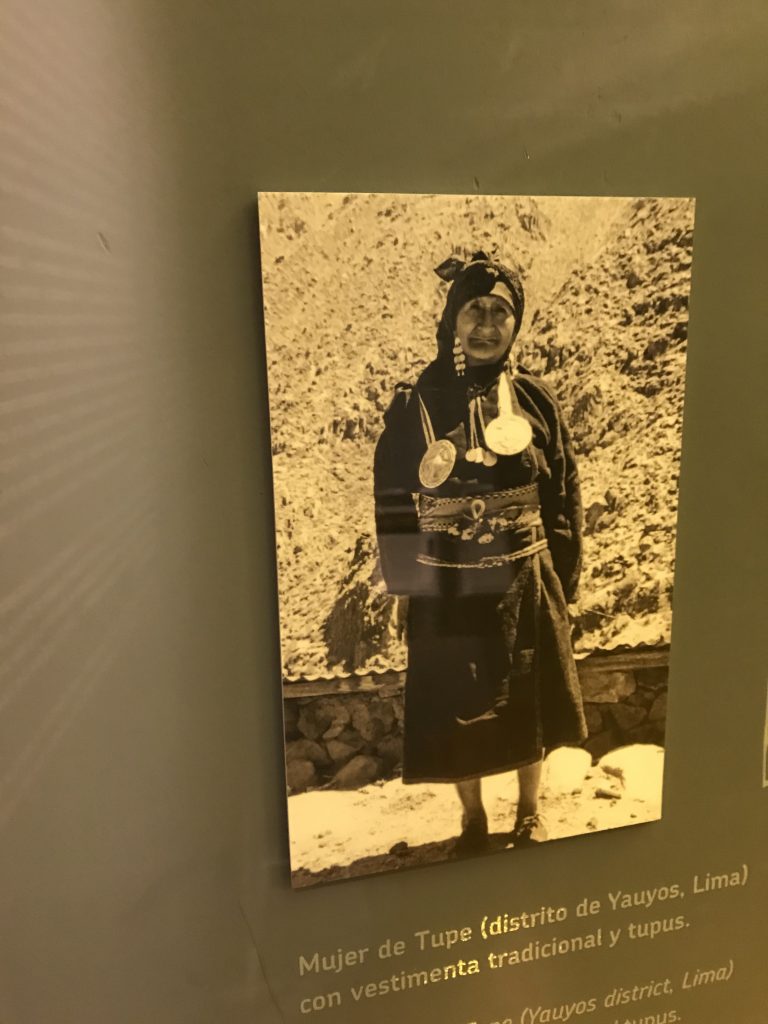

I am looking at one of the display cabinets, at a faded black and white photograph.

“Mayra, there is a place where the people still wear pairs of silver tupus, just like those worn by the Inca queen.”

She comes and stands beside me. The photograph shows an old woman dressed in black, with two tupus hanging from the neck of her shawl.

I read the caption.

“In the remote community of Tupe, women today still wear silver topos at their festivals.”

“That’s fantastic!” breathes Mayra. “Now I remember that Junior, the farmer who showed us the stones, said something about this. People in the mountains who wear lots of silver and speak their own language.”

“The people speak Jaqaru, one of the root languages of Aymara,” I continue, “Tupe is located in the Yauyos region.”

“Yauyos is the headwaters of the Rio Mala, and Cañete,” says Mayra, “upriver from Cochineros. These people would have been neighbours – maybe two or three days journey away, but neighbours nonetheless – to those who drew on the stones.”

“Maybe we should visit,” says Mayra, “but there is a lot we can do here in Lima first.”