I have spent the week examining the photographs, looking for patterns, looking for meaning. I have found out what I can about rock art in Peru, in South America, in Mexico and Easter Island. I have researched the history of coastal Peru, the iconography of Chavin, the Moche, the Wari and the Inca. Finally I check out what studies have already been made at Cochineros, and ask Mayra over for a summit meeting.

She arrives with a bagful of makis and picarones to follow, and I open a bottle of Montesierpe. We take them onto the patio.

The sun is sinking into the sea off Barranco, leaving a trail of gold across the waters. To the left, spotlights come on, picking out a Statue of Christ on a hilltop over looking the bay. This was a gift from a Brazilian construction company to a Peruvian president who signed off on their Lima train systems, their irrigation projects still unfinished thirty years later, and the addendas, the changes of contract, that authorised the 20% budget overruns. Some say the image of Christ was designed to resemble that president.

Mayra settles into a chair and takes out her laptop.

“So, what have you got?”

“The same images reappear on rock after rock. So I created a layered plan of the main rocks and began to map their distribution ..”

Her screen shows eight major rocks, and the concentration of figures on each.

“This is not close to mapping everything – just six or seven common images that seem to be repeated. For example, the lines of animals, the concentric circles.”

“The spirals, T-shapes…”

“And the wavy lines . . .”

The serpents . . .”

“No, the streams and rivers.”

“Really?”

“The long serpentine lines here nearly always run down vertical faces, or at least down slopes,” she explains, “they are water flows rather than snakes. Or, of course, both.”

“How can they be both?”

“In the Andean world, things have multiple identities. We talk about anthropomorphs, figures or beings that are partly human in form. The decapitator god of the Moche was half-man half crab. The sculptures of Chavin appear to show priests transforming into jaguars. Think superhero characters with special powers. Those were their gods, and they are returning today, at least to the cinema.”

“So if a serpent is a river, what is the man leading llamas…?”

“Just as the water-serpents flows down steep faces of the rock, so the lines of llamas run horizontally. Many of them are drawn along ledges or folds in the rock face, as if they were on tracks across the mountain.”

“So they are llamas.”

“The neck length, the size relative to the human figures, suggest they are llamas. Several of them are stereotypical llama images drawn with six or seven straight lines, identical to similar images on ceramics and textiles. And they are with human figures, men or women. But to say the man is leading the llamas is going too far.”

“So what else could they depict?”

“Some sort of ritual, a ceremony, or a representation of a bigger concept like fertility. The llama could be leading the woman. We need to research that.”

She grabs a maki and adds wasabi sauce.

“What have you found out?”

“This site is just one of hundreds of rock art sites in Peru, or better to say, on the western flanks of the Andes. There are plenty in Chile too. A lot of them have a similar position, part way up a river valley. Peru has over thirty rivers running down to the Pacific coast, and almost every river valley has a site with engraved rocks, not on the coast, not in the highlands, but somewhere in between.”

“And do people have any idea why?”

“There are a lot of theories. Guffroy wrote a book about the Rock Art of Peru that manages to advance several theories – closeness to rivers, dry areas, river junctions, ancient travel routes, coca growing lands, political or ethnic boundaries, environmental transition zones – without fully supporting any.”

“That’s quite a choice!”

“Indeed. Cochineros is on a river bank near a valley junction beside a track way, in a coca growing area midway between the highlands and the lowlands, in the Chaupi Yunga, a transition zone from desert coast to rainy highlands.“

“So no conclusions there.”

“There are a lot of options. But there is something special about this site. Something, dare I say, unique?”

“Well, tell me!”

“Sure. But first you need to pour yourself a glass of wine!”

Mayra pours herself a glass of Montesierpe, takes a mouthful, and grimaces.

“Why do you buy this?”

“Two reasons. Firstly, it is cheap. Almost as cheap as a good French wine in Europe. Secondly, I like the label.”

Mayra studies the bottle.

“Montesierpe. A drawing of a snake curved round a mountain.”

Montesierpe, Monteserpiente, the name of the vineyard is something like Serpent Mountain. And if you take a look on Google Earth, you can see this long scaly serpent rising up the flanks of the mountain above the hacienda.”

Mayra raises an eyebrow.

“A real serpent?”

Well, it is fifteen metres wide and fifteen hundred metres long. Perhaps it is a river or a waterway, in Andean cosmovision? Perhaps it is a peanut or a crab? But when I asked a woman in the village where was the band of pits in the hillside she said “Ah ya, el serpiente”, and pointed up the hill.

“So it is a band of pits?”

“About 5000 pits, each a metre square, with neat walls of unmortared stone, in a ribbon rising up the mountain side. From Google Earth they look like the scales of a snake. Curious, no?”

“It seems an unnecessarily complex explanation for drinking a cheap white wine. Tell me about the unique properties of our rock art site.”

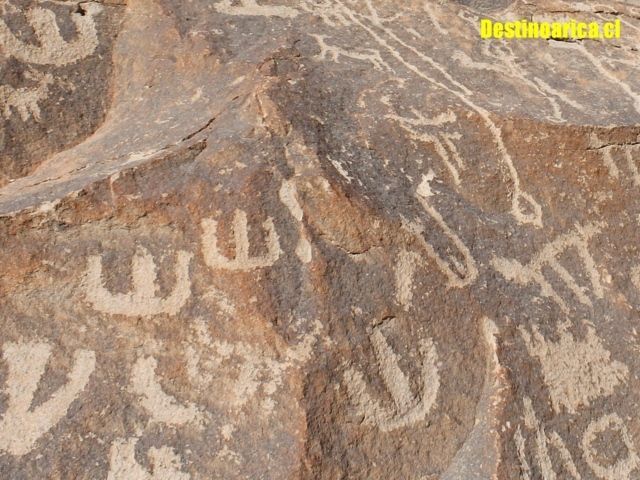

“Did you notice the T-shapes, like a rash that spreads across the site?”

“I plotted their distribution. They are a few on almost every stone. But most are on the stones downstream.”

“That’s right. They are drawn in many different styles: some are rounded, others square; some have ornate handles, others plain; many are roughly scratched on the rock, others are clearly outlined.”

“And a large number are on one or two panels, where there are the dominant image. Whereas, on the other side of those same rocks, there is a complex panel of images, with very few of the Ts!”

“Exactly. It suggests a phase in the history of the site, where people came and drew these T-shapes, more than a hundred of them. They mainly chose to use the panels that had not already been drawn on.”

“The shapes resemble the curved knives that were used for sacrifice,” Says Mayra. “The Inca used them, and so did the Moche, the Chimu, the Wari. They are called tumis.”

“If they are knives, why are they shaped like an anchor or a T?”

“With iron you can make a single straight blade, like our modern knives. But they were working with softer metals like copper, so they needed a central shaft to strengthen the pressure point. Like a miniature spade. Hence the T-shape.”

“Ok, lets call them tumis. Many people visit and draw these tumis in great numbers, in different shapes and styles. But they do not cover the serpents or the spirals. It is as if they respect the older images.”

“Why do you say the older images?”

“Did you notice how some of the images are whiter, brighter? And these are drawn on top of greyer, darker images? Generally the knives, the tumis, are bright, and so are the lines of llamas.”

“You mean …”

“Exactly. We can try to correlate the brightness to the age of these drawings.”

“Many people have tried to date rock art and embarrassed themselves.”

“For now, I am just suggesting the patina of the image, together with superposition, could give us some idea of the age. The beauty of it is, I just have to take photographs, and measure the brightness of the llama or the tumis with software. It is non-invasive, non-destructive. I already have data on hundreds, maybe thousands of images, stored in my camera.“

“But you will need some images of known date to correlate the readings against.”

Yes. And that is what makes this site so special.”

I pour myself a glass of Montesierpe.

We are sitting on the patio looking out towards the sea and the sky. There are no stars, in this city forever under the garua, the low cloud, the belly of the donkey. But along the coast are the brightly lit tower blocks of Miraflores, perched above the sea cliffs, and beyond is the distant port of Callao, whilst the red-tail lights of night traffic move slowly along the coastal road below.

Mayra takes a sip of Montesierpe and says “So what is so special?”

“On the first rock panel we saw, above the patio of vines, I noticed three brooches or shawl pins.”

“Tupus,” Mayra interrupts. “They are shown in engravings of the Inca queens and princesses.”

“Exactly. Long pins with a flat disk at one end, and two opposing curlicues. I counted nine pairs of tupus on the different stones.”

“They were worn in pairs to fasten on the cloak or shawl. They are commonly shown on ceramic figures from Chancay, just north of Lima, and they were also used by the Wari.”

“Which means they can’t give us a date, because they were used by different peoples for a thousand years without a change in design. But these three are drawn over a llama figure – not the stick drawn llama we see in lines, but a solitary, four legged, full bodied beast.”

“So the llama is older than the tupus?”

“It has been overdrawn, and it is also a darker image. On the same panel there is a line of dots running from top to bottom. When I examined the photographs I saw that it crosses over a human figure.”

Mayra looks at my laptop screen as I open up the enhanced contrast image, of a standing man, barely visible, as dark as the stone itself.

“A little further to the right is the bright white heart. It crosses over a spiral, a wavy line and several other dark images. And it is dated!”

“Of course! 1964! So that gives you a correlation of brightness with age. But it will only fix one end of the graph. You need a second point of known date.”

“I think I have one. Listen to this.”

“The valley was so populous, that many Spaniards say, that when the Marquis conquered it, it contained more than 25,000 men. At present, I believe, there there are barely 5000, such have been the strifes and misfortunes they have gone through… …There are scarcely any sheep of the country, because the wars between the Christians have caused their destruction….the large population of this great valley has been reduced by the long civil wars in Peru, and because many natives have been taken away to carry burdens for the Spaniards.”

“That was written by a Spanish soldier, Pedro de Cieza de Leon, in 1550. He was describing the valley of Chincha, a little further south. He described similar scenes wherever he travelled. Like the rest of the country, like this valley, it was devastated by the invading Spanish. They brought disease, and added murderous brutality. 80% of the native people were killed.”

“You are saying no-one drew on the rocks after 1550?”

“We can’t put an exact date on it. But within fifty or a hundred years of the invasion, the fields here would have been deserted, the villages empty, as they still are today. Desolation. It is unlikely that whatever went on here, Whether religious ritual or social activity, or children doodling, would have continued long after the conquest.”

“So the most recent historic markings are perhaps 1530 to 1630.” says Mayra.

“There’s more. One of the researchers who studied the rocks suggested that the tumis, the knives, were an expression of violence, either by a threatened local population or by those who were threatening. He posited that it might be dated to the presence of the Inca, from 1470 to 1530.”

“Which gives you another possible date against which to calibrate.”

“And then we have our modern vandal. He has written his name, JUAN, in dominant capitals, on one panel, and then JNJR, enormous, on a second, and then the giant heart dated 1964, cutting across a much older faint spiral. The style and the brightness of these three are the same.”

“I like it! So what next?”

“I am going to measure the brightness of the images and draw some graphs. If I am making too many assumptions, we will soon know.”

“And I am going to research into tupus and tumis,” says Mayra, “after another sip of Montesierpe!”

“You like it then?”

“Lets just say its getting better!”

***************************************************

18 July 1992. Nine students and a professor disappear from La Cantuta University. The army have been on the campus that night. Head of the armed forces General Hermoza says that military personnel can not be questioned in court for reasons of “security”.

September 1992. Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) Terrorist Leader Abimael Guzman is captured.

1 April 1993. Congressman Henry Pease states in parliament that he has received an anonymous memo from a group of Army officers stating that the La Cantuta students were kidnapped and murdered, in an operation authorised by General Hermoza and Vladimir Montesinos.

Vladimir Montesinos is the presidential adviser who runs the National Intelligence Agency SIN, amongst other things. He lives with Alberto Fujimori and family in the Army base of El Pentagonito, for protection, and teenage Keiko calls him “Uncle Vlad”.

This is the building where journalist Gustavo Gorriti was held after being seized by SIN on the night of the coup. He was released after three days through international pressure.

Later, human remains will be found in ovens in the basement of the building. It is thought that SIN kidnapped, tortured, and murdered people and disposed of the bodies here.

20 April 1993. General Hermoza appears before a congressional commission and denies any knowledge of the La Cantuta operation. He suggests the students could have kidnapped themselves or been taken by terrorists. The Army later issues a statement accusing the Congressional opposition of abetting terrorists. On the next two days, Army tanks and armored vehicles parade round central Lima.

May 1993. Army General Rodolfo Robles confirms that armed forces members formed a death squad called Grupo Colina operating under instructions from Montesinos and with the knowledge of General Hermoza. General Robles seeks refuge in the US embassy.

The Military High Court charges General Robles with insubordination and making false statements. General Picon, a judge in the Military Court, says in a TV interview that Robles had “mental problems” and if he, General Picon, were in the same situation, he would be so ashamed that he would commit suicide.

24 August 1993. Attorney General Blanca Colán closes the civil investigation into the La Cantuta killings to avoid duplicating the work of a recently opened Military investigation.

February 1994. The Military Court finds nine individuals guilty of the La Cantuta kidnappings and murders, and sentences the two commanding officers to twenty years in prison.

January 1994. Demetrio Chavez Penaherrera, “El Vaticano” is arrested in Bogota and extradited to Peru where he is tortured in a military prison. He supplied cocaine paste to Colombian cartels from 1991 to 1993 with 280 flights, two or three a week, from an airstrip in the upper Huallaga valley of Peru. At his trial he says he paid US$50,000 monthly to Vladimir “Uncle Vlad” Montesinos and the local military commanders to allow his flights. He left for Colombia when the tax was increased to US$100,000.

January 1994. After a tied vote from the Board of Prosecutors for the election of the Attorney General, Congresswoman Martha Chavez introduces a law saying that in the event of a tie, the most senior candidate will take the post, to ensure that Fujimori’s 1992 appointee Blanca Colán will be returned to office. It will later be revealed that Montesinos via SIN paid Blanca Colán 10,000 US dollars monthly during her years as Attorney General from 1992 to 2001.

***************************************************

Children kick a football back and forth between two pairs of palm trees that make their goal posts. Dancers dressed in white with yellow belts practice their high kicks and somersaults whilst their capoeira school companions sing in chorus and ring African bells. Mayra is sitting on the steps in front of the old library in Barranco, watching the Saturday strollers in the Plaza de la Familia. We walk through the square to find a back table at Juanito’s. It is the middle of the afternoon, and the bar is still quiet. Two old men discuss the football at a corner table, and a yoga teacher sticks her fliers on the back wall. We order a plate of patitas, pickled pigs’ feet, and two Pilsen Chopp.

Mayra puts her hat and scarf on the table and starts to tell me about her research.

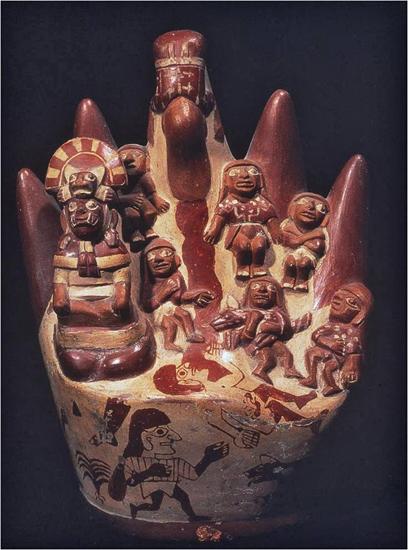

“The original tumis were used for sacrifice by the Mochica or the Moche, two thousand years ago. There are ceramic pots in the Museo Larco here in Lima, showing a girl, bound, bent over a rock on a mountain top, her head hanging over the precipice. The executioner holds a tumi poised over the neck of the victim.”

“What a lovely thing to show to visitors!”

Mayra gives me her “be serious!” look. She is just getting into her stride.

“The Decapitator God was an important Moche deity, sometimes shown in the form of a crab, sometimes a spider usually holding a tumi. The knives were ceremonial, made of soft gold and silver, and shaped more like axe heads. The same implement is found in high status tombs of Sipan, and the Chimu, a thousand years later. They inherited a great deal of Moche imagery and occupied the same region.”

“But all these people were far to the north.”

“Yes, but after the Inca conquest of Chan-Chan, The Chimu capital, the largest city in pre-hispanic America, people from the northern coast were re-settled across the country. Possibly to Maranga in Lima, to Cañete and to Ica. However, their tumis were more rounded. Most of the T-objects depicted on the stones of Chincheros are squarer, more linear.”

“But do they represent knives?”

The yoga teacher asks to squeeze past us to paste more posters on the wall behind the tables.

“I have counted six different designs. Even when they appear to have been drawn together there are different sizes, different types of handle and different shapes of blade. But the most common is the square shape, with a handle in the form of a double ring. This type of tumi was very common in the Inca period – you can see it in museums in Lima. So we can be confident that they represent knives.”

“I have found records of similar images found as petroglyphs, but not nearby, not on the central coast,” I tell her. “They are found near Arequipa, at Sogay, and further south at Chilpe, on the road to Santa Rosario, and then again down in Argentina.”

“All those would have had an Inca presence, and also llama traffic from the coast to the highlands,” says Mayra.

“One researcher suggested all these images were aggressive, weapons, reflecting the insecurity of a time of Inca invasion.”

I reach into my backpack and pull out a paper.

“Here, he writes, “so the engravings of the knives (tumis) and war hammers (porras) … suggest the possibility of the reproduction, within the engraved images, of practices related to physical violence…. We could ask if these drawings that were made by people during the Inca occupation were a response to violent events lived through in the area.””

“It is an interesting idea. The porras, the war hammers, are star-shaped mace heads with a central hole for the shaft. But I see only eight of them drawn on the stones, compared to eighty tumis. And if you are representing weaponry, why draw the head without the shaft?”

“What about the tumis themselves? The way they are drawn, roughly, hastily, overlapping, is in contrast to the majority of other images which are drawn with great care.”

“I agree there. Their form suggests another people with a different purpose.”

“So, the Incas rampaging through the valley, drawing knives on the rocks? Or panicked villagers, gathering to defend themselves?”

“From what we know, the Incas spent years fighting in the next valley south, to conquer the Guarco, and they already controlled some coast to the north. The Mala people, caught in the middle, most likely saw sense and accepted their presence. In any case, drawing pictures of weak copper knives best used for slicing cheese is not a great response to imminent invasion. It’s like waving a fork at the Inca army. Who would have had spears, bows and arrows, slings and stones, maces, lances, and shields.”

“Do you have a better explanation?”

“The author of that particular paper talks of the Inca as “an exploitative and coercing political institution which had expanded through the Andes to control and appropriate…” etc etc. He saw the Incas in Mala as a dominating power.”

“And weren’t they?”

“Maybe, and yet they forged an alliance of mutual respect with the oracle at Pachacamac. My point is that this researcher had a perspective born of his time. In other papers he quotes Marx and Engels, and talks of dialectic.”

“You are talking about the years of terrorism, of Sendero Luminoso.”

“The author was born in Peru in 1974. When he was twelve, 224 prisoners were massacred by the Army and Navy in assaults on rioting prisoners in two jails near Lima. When he was studying at San Marcos, Sendero Luminoso were handing out leaflets on campus and spraying their slogans on the walls. By the time he was twenty-six, almost seventy thousand people had been killed or disappeared in the conflict between violent terrorists, the Army and the police, and government-backed peasant militias.”

“You are suggesting he saw everything, including his archaeological studies, from a perspective of violent conflict?”

“I wonder if when he writes of “… the reproduction, within the engraved images, of practices related to physical violence….”, and again, “….if these drawings … were a response to violent events lived through in the area…”, he is reflecting his own experiences.”

“Well then, if you don’t relate this to Inca invasion, what is your hypothesis.”

She smiles and takes a mouthful of beer.

“In 1750, on June 21 to be precise, an Indian made a solemn confession to a catholic friar, and said he had been involved in planning a revolt. The secrecy of the confessional is one of the most solemn and sacred tenets of the religion. But the catholic friar came to Lima and visited the Viceroy in private to tell him of the plot.”

“And the Spanish were able to stop it?”

“The Spanish sent two indian spies to find out more. June 24 was the Feast of San Juan. A time when communities gathered together to drink and dance, and people travelled to visit their relatives in other towns. The Indians used this as cover to advance their plans and spread the word.”

“But the spies found out what was planned?”

“Esso es. Exactly. Two days later the Spanish arrested eleven organisers. Four were sentenced to hard labour for life, and six were hung and quartered in the main square of Lima, their hands and heads hung from the city walls. The eleventh was of mixed race, so he was given just 200 lashes.”

“I did not realise that the Peruvians continued to rebel against the Spanish as recently as that.”

“That was not the end. A group of Spanish rode up to Huarochiri, with body parts of the executed leaders hanging from their saddles, looking for other ringleaders. They lodged overnight in the town, and 300 villagers came down and attacked them. Only one European was allowed to escape. In a little over a week, the indians had taken control of the province, killing almost all the Spanish but saving the parish priests. Then they organised an advance on Lima.”

“So… they send various militias from the heights of Huarochiri, down the river valleys, recruiting reinforcements?”

“And they visit their ancient sacred places on the way.”

“They are in a hurry, but they want to make a gesture to their gods.”

“This is a rebellion. They are calling on the old gods for support. They don’t really know the significance of the site. It is more than 200 years since the Spanish came, and the population of the valley has been decimated. But they respect it. They don`t draw over older images.”

“And there are fifty, a hundred of them, all drawing this symbol in their own different styles.”

“They dash across the river – it is late June, and it should be low enough to cross. They quickly leave their marks, perhaps as an offering, or a request, or a message to the communities they are passing through. “Get out your knives!”

“But, still, this knife is not a weapon, not against Inca slings and lances, still less against Spanish guns!”

“I thought that too. But then I realised that the original plan was to take Lima by night, in secret. Servants creeping upstairs. They could not take on the Spanish in a battle. But they could slit their throats as they were sleeping. Remember the Spanish who rode up to Huarochiri and stayed overnight? There were sixteen of them, and 300 villagers gathered in the night to kill them. Knives will do if it is all you have.”

“It is a great story. But is it true?”

“If it is, we might find the same markings on rocks all the way up the valley, from here to Huarochiri. And in other valleys too. But you think you might be able to date these drawings. Could they be 1750?”

“I will have to look at the images and do some analysis. But I accept the challenge! Now we should get some more patitas, some bread and sardines, and a couple of beers.”

**********************************************