A casual visitor to Cochineros may assume that it shows the undisciplined scrawls of hundreds of random people. But the site has a thousand images engraved over almost two thousand years. An average of less than one image per year speaks more of careful ritual.

Given that time scale, the site has clearly been used in different ways and by different people over the centuries. The images are layered like history itself, and their interpretation is just as complex.

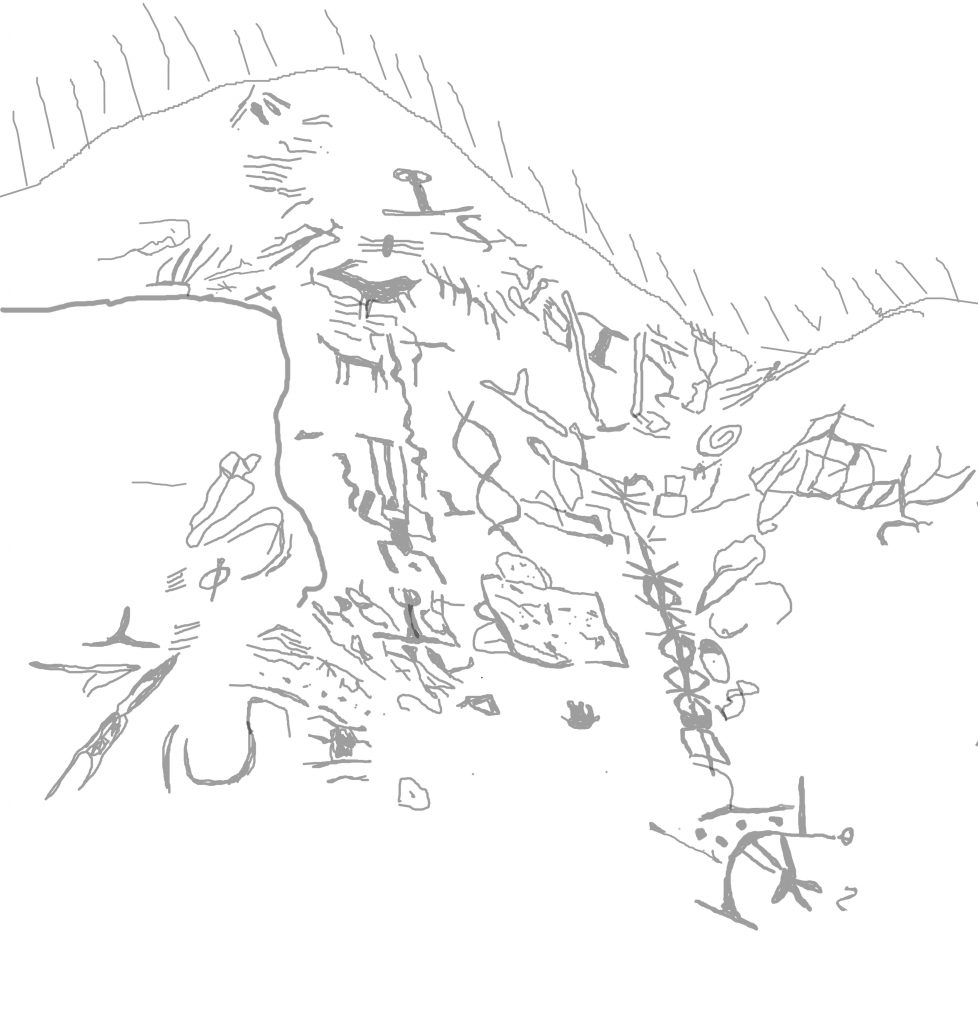

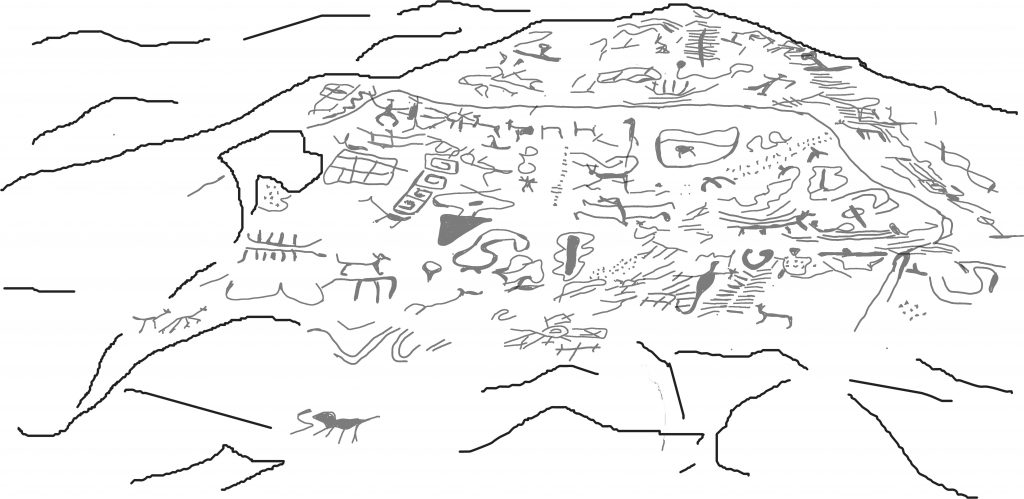

There are simple freehand sketches across the surface, and images deeply engraved into the rock, several millimetres deep; some are outlines and others are enclosed images; there are embellishments and additions to the natural rock, highlighting cracks, profiles and holes in the surface; finely outlined drawings and roughly made markings; big statements and tiny footnotes.

There is a great richness to the art here, more, than at sites such as Miculla and Checta, because there is a wide variety of different influences. Even images seen repeatedly at Cochineros – llamas or human figures – are drawn in many different styles. The overall impression is of a vibrant cosmopolitan sharing of ideas over time with an exciting variety of imagery and execution. Huancor has a similar depth and complexity, but Lunahuana, for example, does not.

All these people, writing on the same rocks and panels, chose on the whole to write side by side. There is little sign of older markings being deliberately damaged or overwritten. The tumi artists have been envisaged as an aggressive, invading gang, and that is the impression of their impact on Piedra 12. Yet they carefully placed twelve small tumis into the gaps between existing images on Piedra 6.

The site expresses up to 1500 years of cultural continuity rather than the domination and destruction that have typified the last five hundred years.

Three stages stand out. First of all the dark images. They are abstract, rich and varied. They include lines of points, square grids, parallel lines, chevrons, patterns of dots, ovals and stars, figures of eight, slashed lines – they appear to have little parallel in known ceramic or textile iconography, but a careful study may change that.

In the next phase, from a thousand years ago, the rocks take on individual characteristics. Certain symbols cluster on particular stones or panels. Many have one large image, prominently displayed towards the peak of the rock.

The most recent phase is evident in brighter images – rectilinear llamas, paired felines, fish, foxes, fantastic birds. These are familiar figures from textiles and metalwork of the central coast, standardised images that are found from Chancay through Lima to Pachacamac and Huaca Malena.

In some cases, these marks seem like the traces of a raiding party, drawn just once on several panels. Three fantastic birds, Chimu or Chancay style, are drawn on three rocks on the eastern edge of the site, close to the river. They are drawn on the lowest portion of the rock, or the part most hidden from the terraces. One bird appears to be half of an incomplete pair of complementary motifs.

The same happens again with several fox or dog figures, so similar that they could have been drawn by the same hand. They are drawn low down on the riverside faces of Piedra 12 and Piedra 6b. Like the birds, they could have been drawn without being “seen” by the Paria Caca rock or the centre of the site.

The tumis repeat the pattern, but more dominantly. Piedra 12 has been overrun and possessed by tumis, with a large tableau on the central peak of the rock, surrounded a ring of finely drawn tumis facing out and down. Elsewhere, they have been drawn on almost every rock, but smaller and less carefully. It looks like a takeover of the rock, or a playing out of the ritual of conflict.

In 2021 I discovered a review of metalwork found at sites across the whole of Peru that concluded that at T-shaped tumis were closely linked with Inca presence, and curved tumis and mariposa tupus were not.

“we can identify several bronze object types that were widespread enough to suggest that their distribution resulted from, or was facilitated by, activities of the Inca state: tupus with half-round heads, tupus and T-shaped tumis with animal heads, T-shaped tumis in general…” in Owen, Bruce D. “The Meanings of Metals: The Inca and Regional Contexts of Quotidian Metals from Machu Picchu.”

So the site was overrun by Inca T-shaped tumis, superseding the rounded northern coast designs.

These events, and the difference in patina of images, suggest that the uses of the site changed over the years. If we discount the more recent additions, and view the rocks with a fresh eye, we gat a different perspective.

If one rock came to represent Paria Caca in the later stages, then other rocks in turn may have represented different gods or ancestors.

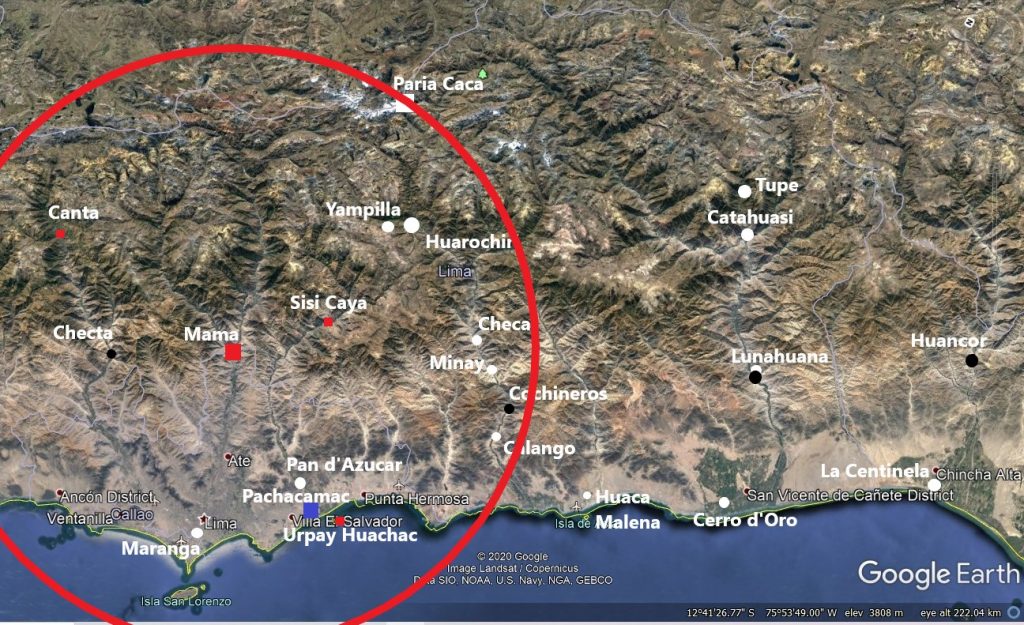

Yampilla on a hill a league’s distance (4 km) from Huarochiri, was said by Polo de Ondegardo to consist of seven large rocks representing several idols, including Pachacama, Punchau, Paria Caca, and Chaupinamoca (in Siete cartas ineditas del Archivo Romano de

la Compania de Jesus (161 1-1613))

The home turfs of these idols are a considerable distance away. Yampilla is fifty kilometres south-east of Chaupi Ñumca’s centre in Mama, seventy kilometres east of the Pachacamac oracle on the coast, and thirty kilometres west of Paria Caca’s probable shrine. If Punchau, sun in Quechua, represents the Inca sun idol, then its seat might be considered to be in Cusco.

Yampilla then was a local centre, with satellite shrines for deities whose primary locations were much further away.

Other Huacas were represented in several places. For example, Chaupi Ñamca was based in Mama but she had four sisters: Llunoc Huachac, in Canta, fifty kilometres north, in the Chillon valley, Urpay Huachac, by the seashore or in the ocean; and two more, Llacsa Huato and Mira Huato, who lived together in Chillaco (in the Lurin valley, close to modern day Sisi Caya).

The same Urpay Huachac was said to be a major Huaca for the Chincha, but presumably attended to at a shrine in the Chincha territory, 150 km south of Pachacamac.

Here we see a network of deities and shrines linked to each other, stretching from the coast to 70 kilometres inland and across several neighbouring river valleys.

Paria Caca and Pacha Camac similarly had several kinship shrines – children – spread across the region, possibly across the country.

This resembles a franchise system would have extended the reach and power of the shrine, and in turn offered the local satellite shrine the prestige and authority of a major deity.

The Huarochiri Manuscript relates how shrines can be relocated, can fall into disuse, and can be brought back into service. The Incas, it is said, would “capture” local shrines and take them to Cusco.

If Chaupi Numca’s sisters represent an expansion of the cult, then it is ineffective to have two sisters at the same site in the Lurin valley. The Huarochiri Manuscript is somewhat vague here.

” Concerning this Mira Huato, we aren’t sure where she lives. But people say “she lives with her sister Llacsa Huato”.

The sisters have alternative names, meaning second and third born in Checa, the language spoken upriver, in the highlands beneath Para Caca. Would it not be more fitting for the sisters to be located in successive river valleys along the coast, as female representatives of the fertile lowlands? One sister is based in the sea or by the sea, but the other four are positioned in the neighbouring valleys of the Chillon, the Rimac, and the Lurin (two sisters).

The next valley south with running water is that of today’s Rio Mala, then called the Huarochiri. The lowland people living there were the Calango or Carango, who we know took llamas to Paria Caca on his feast day.

Further south still and we reach the Cañete, where lived the Guarco and the Runa Huana (around today’s town of Lunahuana). All these five rivers flow directly from the lakes beneath the peaks of Paria Caca. In a mystical sense, they could be Paria Caca’s five daughters.

Perhaps Mira Huato, the second sister in Sisicaya, had been based further south and was temporarily relocated to the Lurin valley. Perhaps she was based on the banks of the Huarochiri, at Cochineros.

This would match the range of influence of Chaupi Ñumca. Based at Mama, she was the sister of Paria Caca. Another sister, Urpay Huachac, was married to Pacha Camac. A circle centred on Mama that extended to those close family members would encompass her sisters at Canta and Sisi Caya, the shrine to her at Yampilla, and also the stones of Cochineros.

Today in Lima’s historic centre, the Spanish Catholic Cathedral in the Plaza de Armas has similar satellite shrines. There are thirteen in all, to deities from Cusco and from Ayacucho as well as to John the Baptist, from Palestine. Those families who have moved to Lima want to light candles for their familiar protectors from back home. Prehispanic society in the Central Coast was also mixed, as personified by the links between Paria Caca, Pacha Camac and Chaupi Ñamca – highland mountains, mid-range valleys, and the coast.

****************************************************************

Sixteenth century chronicler Christobal de Albornoz was a Spanish priest who set out to discover as much as he could about native sacred sites in order to destroy them. He wrote that the most sacred deities or oracles for the Chincha were Urpay Huachac, an offshore island, Cuyca, “a stone which has many stones around it, on the flats of Chincha called Ylauequi llanay”, Chinchay Cama, and several others around the town, as well as a star; those for Luna Guana (Lunahuana) were Muyllu Cama, a stone on a hillside near the town, Sulca Vilca (“on a hill besides the sea… said to be a brother of Pacha Camac”, maybe located at Cerro Azul, the tall headland below Cerro d’Oro), and Conca Vilca (a stone on an island in front of Sulca Vilca); for the Ychsma there were Pachacamac in the form of a golden fox, Tanta Namoc, another fox, Aysa Culca (a stone in the form of an indian in Manchay), Rimac (which may have been located between today’s Barrios Altos and the Plaza de Armas in Lima), and Sulco Vilca (“a Huaca of the Sulco (Surco?) indians, was a large stone … on a hill besides the sea…”). So many stones.

If the site at Cochineros was a local group of satellite shrines like Yampilla, it might be expected to house shrines to a deity from the highlands and one from the coast; one to the north and one to the south; one male and one female, and so on.

Of the 20 stones at Cochineros, five or six are dominant because of their size, the number of images engraved on them, and the historic depth of the imagery. Can we find any clues as to what they might represent?

I have already suggested that Piedra 11 with its double peak represents Paria Caca. At the opposite end of the site, Piedra 1 has a preponderance of flowing streams down the vertical eastern face, eight of them, as well as concentric circles, repeated five times, and tuber-like images on the vertical face. There are four more serpent streams descending the upper surface.

The concentric circles vary from bright and clear to hardly visible, suggesting that this particular theme for the rock was long lasting.

There are also several pairs of tupus, and some individual tupus, all with the ornate head of the pin pointing down, along what would be natural channel of water flow.

In the Andean world, as we have seen, running water is a male element running from the heights down to the warm female fertile valley soils. Tupus are generally linked with women as decorations and as grave goods.

Salomon, the author of an astounding translation and explication of the Huarochiri Manuscript (and much more), writes “Societies on the Pacific slope of the Andean chain saw themselves as partnerships between lineages of highland pastoral origin, identified with male Huacas incarnated in snow caps, and lineages of valley based agriculturalists, identified with valley based female fertility Huacas. In . . . Huarochiri . . . union connecting the powers of the heights (storm and water) with those of the valleys (soil and vegetation) was often mythicized as a sexual union or sibling pairing between invading male water deities and deep-seated, unmoving female earth deities.”

Paria Caca Rock is prominent, outstanding, whilst this Piedra 1 is very much “deep seated.”

So if this rock embodies themes of fertility, growth, and womanhood, might it have been a daughter or sister shrine for Chaupi Ñamca?

Streams of water running over this rock, and its tupus, would be an act of fertilisation, and the concentric circles could represent fertility as a metaphor for expanding wombs, growing fruit or tubers.

Rituals here could have included diverting a canal to create a flow of water over the stone. This would account for the dark band of varnish which stains the vertical face of the rock.

************************************************************

If the upstream part of the site is a female area, with themes of irrigation and growth, then what can we make of the two great boulders downstream?

The southernmost rock had a historic dedication represented by the dark abstract images, particularly on the panels facing south. The peak and sides were overtaken by the sacrificial knife cult, the tumi images, some five hundred years ago. They added their signature image to other rocks at the site, but in a respectful manner, between existing engravings. Whatever this represents, it does not match the creative range or the technical quality of the earlier work. It seems, for the most part, thoughtless and undisciplined.

The south facing panel on the higher rock has a few dark images, but appears to have been dedicated to the Paria Caca cult around one thousand years ago. This dedication continued for five hundred years.

On the panel facing north here the images are less clear, with the entire surface presenting a grey appearance and small, scattered, unclear images. There appears to be no unifying theme or themes.

It may be that a closer analysis of the iconography, and particularly the dark images, would shed more light on this. But each rock, each panel has drawings over a considerable period of time, which could reflect several changes in the use of the site.

The eastern facing panels of the Paria Caca rock are difficult to see faces. For most visitors crossing the river, images here are all but invisible in bright sunlight. Jimenez did not record them and neither Tantalean nor Guffroy mention them.

In the late afternoons close to the June solstice, however, the the sun reflects off the rock at a helpful angle for an observer correctly positioned to the south.

The panel is split by a great crack. The two sides appear to descend from the two peaks of the rock. One the right there is one dominant human figure and a dozen smaller motifs. These include a repeated horseshoe figure which spreads across both panels. The left hand side of the panel is completely covered with drawings from top to bottom.

An enclosing circle encompasses a large part of the panel. There is a trail of twenty birds or crosses ascending on the right. Four swallow-like birds also fly upwards. The bird figures are repeated at the peak. The top of the panel has what may be a spider, and the ridge is notched. Two tupus and three tumis stand out bright white.

****************************************************************

There is an intriguing account from one of the Jesuits who accompanied Avila in his journey to destroy sacred sites around Huarochiri. It is the same Polo de Ondegardo who described the visit to Yampilla. He now talks of what they did the following day. It is worth quoting in full.

“El segundo dia fueron los P.es con otro tanto numero de yndios, y con el Doctor Auila su juez en esta causa mucho mas lejos q. el primero, y por vnos caminos muy peligrosos a deshazer el famoso ydolo Xamuna q. dizen fue vn hombre muy valeroso q. ayudo los yndios de estas tierras en ciertas guerras, despues de las quales vino a este Cerro, y se conuirtio en vn gran risco; llamanle tambien Huaranca Xamuna porq. dizen q. era tan valeroso q. con ser vno, quando era necessario se hazia mill, de tal manera q. pareqia una gran bandada de paxaros con lo qual venqia a sus contraries.”

Loosely translated, the Jesuit writes, “on the second day the Priests went out again with many Indians and with Avila and his judge a much further distance, and on dangerous roads, to bring down the famous idol Xamuna, who they said was a great warrior who helped the Indians of these lands in some wars, after which he came to this mountain and became a great cliff.”

“They called him also Huaranca Xamuna (Xamuna the Thousand) because he was so brave, that although being one, when it was necessary he became like a thousand, so that he seemed like a giant flock of birds to vanquish the enemy.”

A deity close to Huarochiri and Yampilla was noted for appearing as a flock of birds to defeat his enemies. He was an ancestral hero so important that two hundred burials were placed around him. This perhaps offers us a clue to the hidden panel with its flock of birds, on an adjacent panel to Paria Caca. Could it have been dedicated to Huaranca Xamuna?

*********************************************************************************

If Cochineros was a shrine to several deities of the central coast and highlands, it would have had its resident priests and priestesses to speak to the shrine on the behalf of supplicants and pass on its response. There would perhaps have been places to make sacrifice, to consult oracles, and to store offerings. There may also have been burials for the families who supported the cult, or for those who served the deities.

Beyond the northernmost rock, there is a pair of bright white vertical stones, like low doorposts. The stones stand in front of a platform six metres long and four metres wide. It appears to be the remains of a rectangular building of indeterminate age.

Then there is a series of descending patios between this building and the river, that appear to house tombs, or underground storage rooms. There are ceramic fragments here, pieces of cloth, and occasional fragments of bone. Could there have been privileged burials near to this sacred site, perhaps the serving priests and priestesses?

What would have happened here, on the banks of the river? It may have been a centre for seasonal festivals, an open space where many could gather and drink and dance. There may have been music, such as the men playing long trumpets which the stones depict.

They could be drinking chicha, maize beer, a the ritual drink, and they may have added espingo, as a spice or a hallucinogen, or vilca. At a harvest festival, they might cook the first crops, potatoes or maize, and share them around.

There might have been a speaking oracle, with a priest to act as the spokesperson for the deity. They may have had to enter a trance state – with drink and drugs – before they could communicate. The daily visitors to the oracle would come in ones and twos.

At a church in highland Huancayo several hours from Lima I saw a sign on the door saying in Spanish “only white candles here, no paganism”. Yet around the church were stalls and kiosks selling a range of brightly coloured candles, red, blue, and green. The women told me that each colour has its own meaning depending on the what is being asked of the gods. In the plaza besides the church was a cast iron stand where hundred of these coloured candles had been lit by the faithful.

In Lima Cathedral the devoted leave offerings – lighting a candle, or pasting to the wall little silver replicas of a heart, a leg, a hand – at the side shrines with their figures dressed in silver and gold of deities from Andahuayllas and Puno. This is very catholic, and it may also be similar to the ancient rites.

I was reminded of Junior, a farmer lower down the valley, who told me that whilst planting amongst the stones he had found a bag of woven vicuña containing coloured beads on one occasion, and a small silver figurine on another.

“They bathe Chaupi Ñamca in a little maize beer, lay out all sorts of offerings for her, and worship her with guinea pigs. They used to stay there all night long, dancing, drinking and getting drunk until dawn.”

“They dance the Huantay Cocha, the Ayñu, and the Casa Yaco. When they dance the Casa Yoco, the men would dance naked, or wearing only jewellery. “Chaupi Ñamca enjoys it no end when she sees us like this” the dancers would say. After they danced this dance, a very fertile season would follow.”

“All the people called Chaupi Ñamca “Mother” when they spoke to her. When people sought Chaupi Ñamca’s advice on anything, she would answer “I will go and talk it over with my sisters first.”

“During her festival the villagers would dance for five days. Those who had llamas would dance wearing puma skins, and people would say “they are the prosperous ones.” They still celebrate this today, in the valley of Mantaro, every June, wearing masks of foxes and brocket deer.”

The Huarochiri Manuscript describes other festivals but they have much in common. People from a wide area coming together, on a specific date, making offerings, dancing throughout the night, getting drunk for days on end. That, I imagine, was the scene at Cochineros 1000 years ago. It has many elements, music and dance, food and drink, rites and rituals, but the core is the coming together of people for an occasion of bonding and sharing. And a site such as this would bring together people from both coast and highlands, from this and neighbouring valleys.