Abstract

A non-invasive method is trialled for date ordering certain petroglyph elements on a rock panel at Cochineros, on the river Mala, south-central Peru.

The petroglyphs have been engraved into a dark rock varnish coating to give a strong contrast between the white crystalline powder created by pecking or scratching, and the black background of the rock surface. The brightest image is a modern heart with an inscribed date of 1968.

Several superpositions of lighter elements over darker support the theory that the images have darkened with age.

The intensity of elements was measured from digital photographs using freely available medical imaging software Fiji/Image-J. Measurements were found to be robust and consistent, within fairly large error margins of around 3%, for images taken on different days and at different times.

The change in intensity of the elements appears to be due to the growth of rock varnish over the panels, perhaps combined with other factors. Although little is known with certainty about the growth of rock varnish, despite considerable study, it may be that over a small time scale of one or two thousand years before the present, constant growth is a reasonable approximation at this particular site. In any case, it is the simplest assumption. This provides us with a quantitative dating.

If the rate of growth is not constant, but is nevertheless consistent, in that it continues to grow over the time period rather than erode, then the qualitative date order of the different elements will still be vaqlid.

The results measurements of intensity helped group some elements on the basis of their intensity, their style and their subject matter.

A long history of engraving at the site is suggested, with a succession of people using it in different ways. The proposed dates for the pre-hispanic petroglyphs vary from 440 to approximately 2000 BP.

A narrative is proposed for the several stages of use of the site.

There are some panels at the site, that have a wealth of imagery but are difficult to access. One particular panel with an area of around 15 square metres displays largely dark, abstract images. It might be possible to extend the dating by using stylistic similarities between images on the panel analysed here, and other panels, together with measurements of brightness, by using drones or otherwise accessing these panels.

Given the scarcity of alternative dating methods, especially those that do not require destructive sampling, even the relatively rough age estimates obtained here are a valuable contribution to the archaeological study of rock art.

Introduction

The Cochineros site comprises a group of giant boulders mostly on terraces above the river Mala, seven kilometres above La Capilla and a kilometre downstream from Huancani. There are nine large boulders, with panels several square metres in area. Three boulders have engraved areas totalling more than twenty square metres. Five boulders appear to be dominant, in terms of the quantity and quality of engraved images. In total there are at least twenty stones with images, seventeen of a black diorite or andesite and three minor stones which are reddish-brown rather than black.

The site is not unique in the area. There are two boulders, one large and one small, across the river at Retama, 500 metres downstream. From these boulders it is possible to look upriver and see the Cochineros site. There are also petroglyphs with stylistic similarities to some of the Cochineros engravings, located 4 and 4.5 km downstream at the side of the road between La Capilla and Cochineros, 5km upstream at Minay, and 13 km upstream at Checas. All these are engraved on the same dark stone. There is also a petroglyph in the centre of Minay village which is on red-brown stone rather than the black diorite. There is a noted petroglyph stone at Calango which differs in type of stone and the nature of the engraving. The site and the petroglyphs should therefore be seen in the context of the valley, which appears to have been a pre-hispanic route from the coast to the highlands. A road up the valley is well preserved in many places, are are ancient settlements along the valley.

The first investigation of the engravings at Cochineros began with a visit by the Cuban scientist and adventurer Antonio Nuñez Jimenez in or around 1976. He published 36 pages of tracings and photographs in his “Petroglifos del Peru”. He did not speculate on the age of the site and what he records is meticulous and almost wholly accurate, although incomplete.

The book does not record perhaps 25 percent of the artwork at the site, including several major panels. Nuñez is photographed sitting on top of one such panel, so he clearly saw and probably recorded some of these images, but did not include them in the published book. His partial recording of images on some difficult to access panels suggests that he did not see some darker images which only become apparent under the right lighting conditions. That is, he was probably looking down on the panels from above, which means the dark images are all but invisible.

Henry Tantalean described the site in 2010 and began to tabulate and categorise the images. He proposed that the many tumis at the site indicated that the majority of images dated to the Inca period. Whilst there are many tumis, they represent less than 10% of the images. Tantalean did not note the dark images.

Photographs of images and panels are included in a photographic record of petroglyph sites by Guffroy in Imágenes y Paisajes Rupestres del Perú, 2009, together with a brief summary of the site. Guffroy suggested that the majority of the engravings at Cochineros and Calango dated to the Late Intermediate and the Inca periods, from 1000 to 1534 CE, though he recognised there might be a component dating to the Intermediate Horizon 400 years earlier.

Measurement

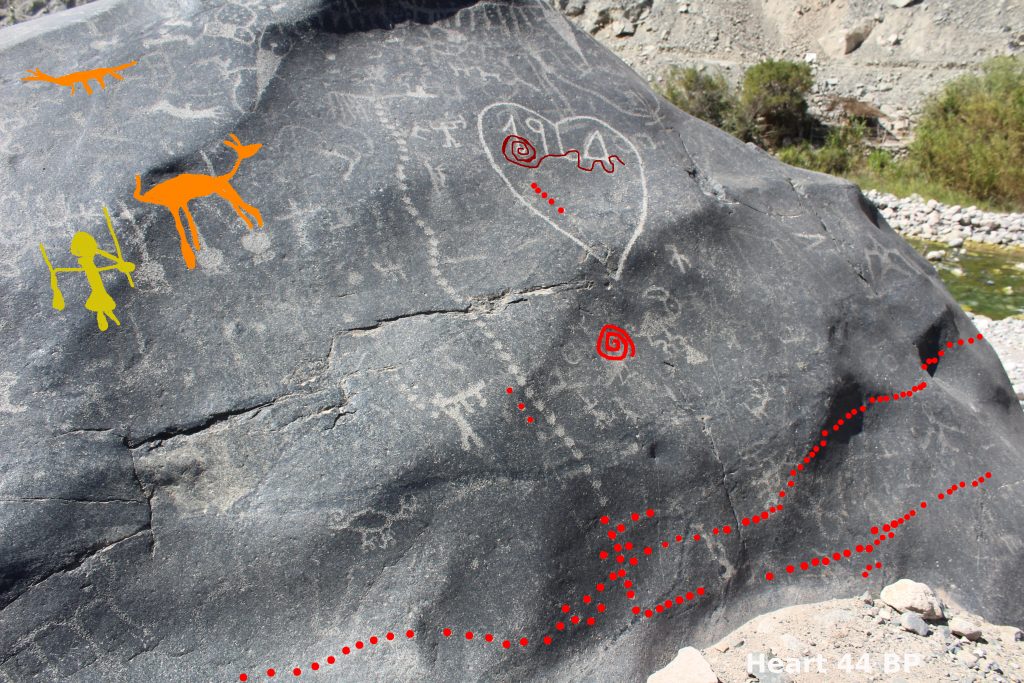

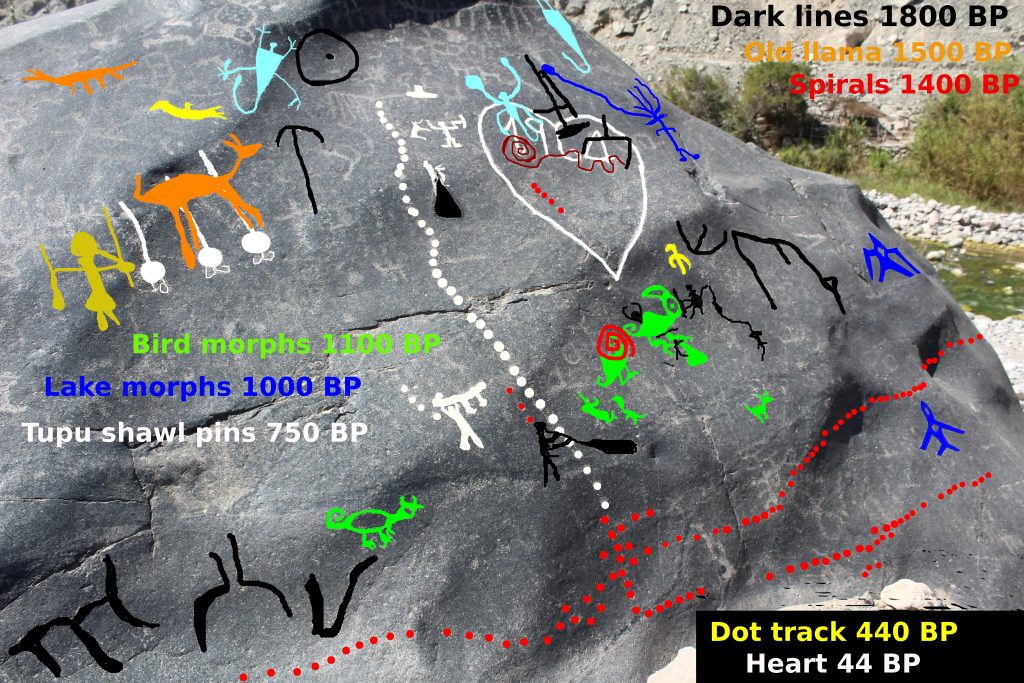

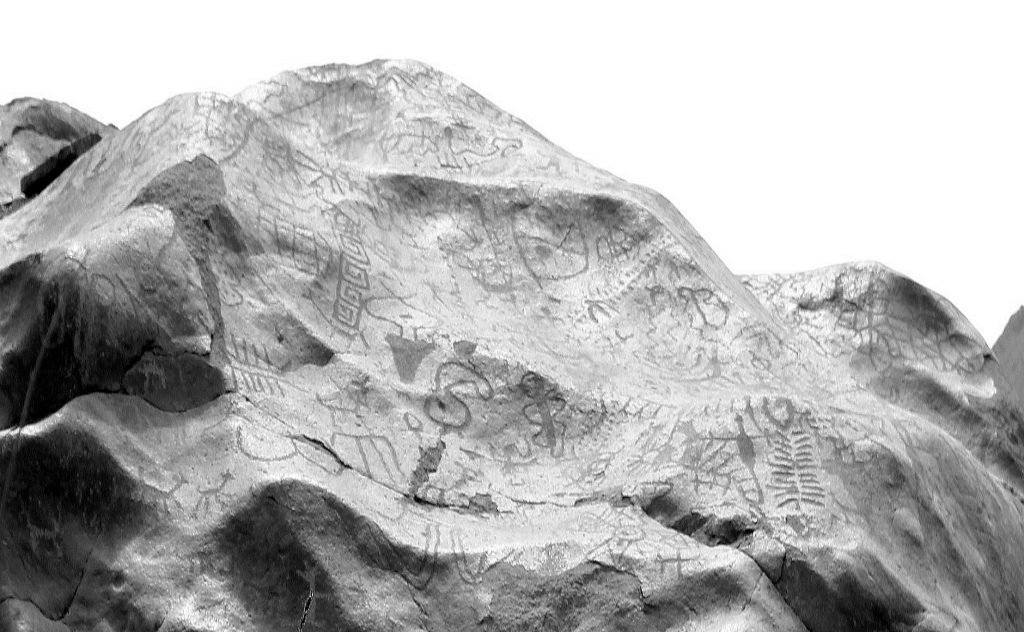

It is evident (Figure 1) at Cochineros that there are brighter, whiter drawings and duller greyer drawings on many of the rock panels. Where one image has been drawn over another image, the newer image is brighter. Such superpositions can be seen with the heart, which is drawn over a spiral and a “lake deity”, and with the three or tupus, to the left, drawn over a four legged camelid.

Under the strong sunlight of coastal Peru, it can be difficult to discern the varying brightness levels. It is more readily observable on photographs of the stones.

If the brightness could be consistently measured, and a relationship between brightness and age could be confirmed, then it would be possible to order the drawings in series by age. If some points in this series could be calibrated, and the mechanism of the change in brightness were known, then we could have a method of quantitative dating.

The panel chosen is a broad flat panel with clearly differentiated bright and dark images (Figure 1), two metres high and four metres wide at the base, rising to an apex.

Many interesting features are evident on this panel. On the upper left there are three elements with a long pin and a round head which represent tupus. These decorative pins worn by women have been found in burials from as early as 4000BP and continued to be used into the colonial period. In fact they are still worn today in communities in Yauyos several hours upriver from the site. They are seen in Chancay ceramics from the Late Horizon and were recorded by colonial artists such as Guaman de Poma. There are over twenty tupus engraved at the site, but I am not aware that they are seen at any other petroglyph site.

These three tupus are drawn over a darker image of a quadruped with a long neck that is probably represents a camelid, such as a llama, vicuña or guanaco

Given their long history, they do not help with dating the drawings.

The comparison will only be valid if the markings are made in the same way. In practice this means that all the rock surface is removed, and the marks are made deeply and evenly rather than just scratching the surface unevenly. Measurement on thin lines is inconsistent.

The images selected were therefore those with a large surface area, well delineated and infilled. There are several such suitable images which I named, without any claim to interpret their meaning, as the Old Llama, the Three Tupus which overlay this, the upper and lower Swallows, three Lake Deities, and an Old Spiral. This last is not ideal due to its relatively thin lines but it is an important central motif. Later I added more but as the images are less clearly and uniformly drawn the results are correspondingly less reliable.

I took images of the rock panel at different angles, one early afternoon in August, and measured the brightness of the engravings as shown on the digital images.

Brightness was measured using FiJi, a version of the ImageJ programme developed at the National Institutes of Health, which can be freely downloaded.

The software could calculate many parameters for the selected area. I chose mean, median and mode grayscale value (average pixel intensity) together with Standard Deviation. The grayscale value or pixel intensity was given as a number between 0 and 255 for jpegs, and 0 to 65,536 for TIFF images.

Measurements were made with both wand and area tools and plotted for comparison. The results were comparable and so the wand was used latterly as it has the advantage of selecting a larger area. the wand area selection giving a large area and representing different parts of the element. Typically, four or more areas were selected and the readings averaged.

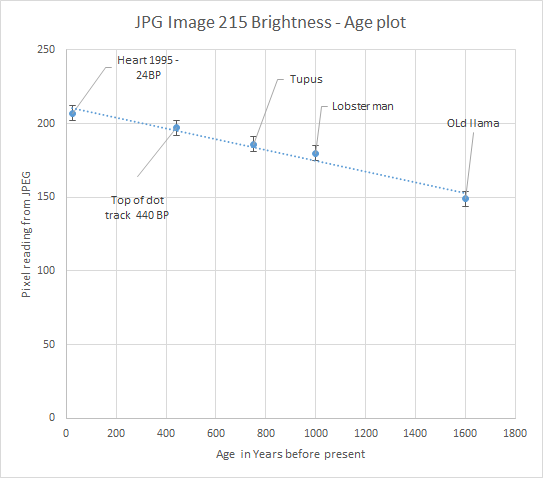

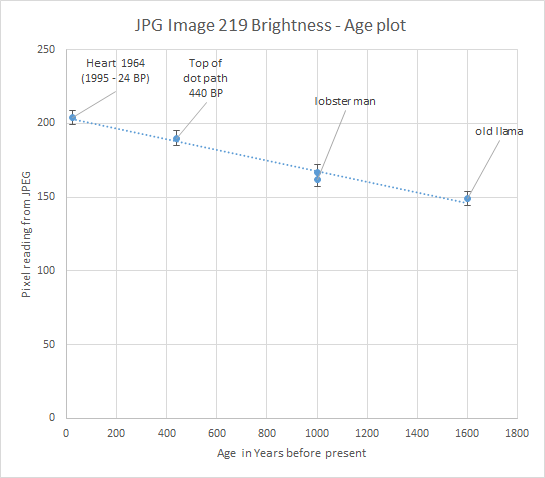

The absolute value of the average pixel intensity of a petroglyph element varied from one photograph to another. However the relationship between the average pixel intensity of different elements was consistent between digital photographs. This can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, showing measurements from two different jpegs taken from slightly different angles to the rock panel.

This tells us that a digital camera image consistently records the relative brightness of different elements of a petroglyph panel.

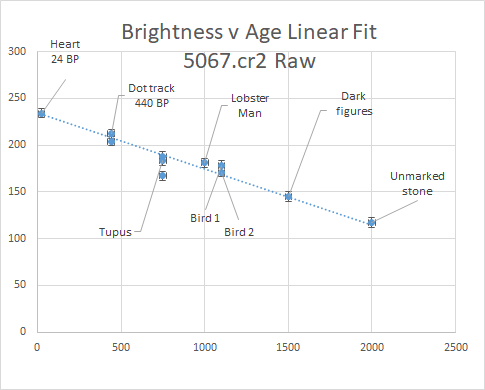

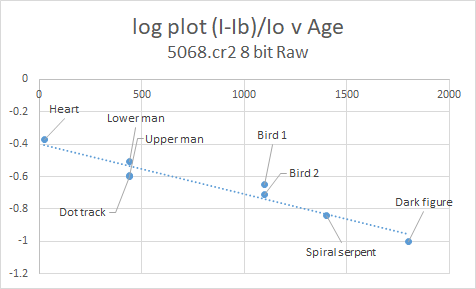

But a simple digital camera adjusts the image brightness in a non-linear way to compensate for the human eye. So I repeated the measurement with a more sophisticated camera a year later. This gave me unprocessed images, so-called RAW, which measured the pixel brightness without correction.

The next step was to relate these measurements to the age of the images. There are several clear over-drawings on this panel. For example, three tupus, or shawl pins, have been drawn over a less distinct camelid, the Old Llama, and the Heart has been drawn over a spiral. The images drawn on top, such as the tupus, are brighter than the images over which they are drawn. This suggests the darkening process is time related.

But to determine the absolute age of the images I want to calibrate with images of known date. Here I have a powerful aid, in the otherwise deplorable graffiti on the panel, the heart which is dated 1964.

There is a minor complication here: it seems unlikely that “1964” is the date of the drawing, since it is not shown on Antonio Nuñez’ Fig 1488 sketch of the rock surface.

Nuñez was Cultural Ambassador to Peru 1972-1977 and published his four volume work on Petroglyphs of Peru in 1986. So the heart would appear to have been drawn after 1972. The heart is seen on a photograph by Tantalean which was published in 2010, though it could have been taken some years earlier, as he wrote about the site as early as 2005.

It could be that JUAN or JMJR – which are inscribed in the same style on other panels – met his partner or got married in 1964, and the engraving was made twenty or thirty years later. For the purposes of calibration, these uncertainties in date are not significant, compared to the uncertainty in pixel brightness values. I have taken the date to be between 1972 and 2010 or 1980CE plus or minus 20 years as the calibration date for the heart.

A second calibration point is provided if I assume that drawings on the rocks did not continue long after the Spanish invasion. The Spanish reached Pachacamac in 1533. They founded Lima in 1535. In 1571 the Reducciones began, and Peruvians were forced to move to new settlements under Spanish control, such as Calango. By 1586 Corregidor Davila Briceño had moved the people 0f 200 Yauyos villages into 39 Spanish centres. In 1608 the Extirpacion de los Idolatrias began its visits throughout the Huarochiri region, destroying sacred sites, and intimidating those who practised the indigenous religion. In this context, it seems unlikely that people would have continued to visit their holy places and leave their marks upon the rocks, after say, 1580CE. The calibration is not particularly sensitive to variation is this date.

Assuming a linear relationship, I then simply draw a calibration line, using the two images, the heart and the dot track, of known age. The brightness of other images, whether measured from two jpeg photographs taken in 2017 or four RAW images taken weeks apart in 2018, fit to this line consistently. The brightness scale as determined from photographs is robust for other images on the panel.

Using a linear fit gives age estimates for different images that span around 1500 years.

The fit takes us back from the bright heart, around 1980, past the dot track of 1580, to the tupus, around 1300CE. Older still are the lake figures at the top of the panel, holding up the mountain, dating to around 1000-1200CE. And then we can see before the Late Intermediate Period. The two swallows flying up the side of the panel may be 900CE but the spiral on the centre of the panel – it is commonly proposed that central images are the earliest – is closer to 600CE, while the Old Llama, the four legged camelid over which the three Tupus were drawn, may be 500CE.

The uncertainty in the brightness measurements means that each of the dates quoted is plus or minus several hundred years. But the overall picture is of a panel added to over a long period, with different motifs and styles.

To justify using a linear fit, I want to know what is causing the engravings to darken with time. Localised darkening can be seen on some rock surfaces. Piedra 1 (Figure 2) has a long vertical panel facing the river. At its foot is a white horizontal band above the present ground level, which is broken in the centre by a dark vertical band which descends from the upper surface of the rock. Some of the tuber shape element above has been darkened. The darkening is not uniform but parts of the tuber could have been redrawn.

The appearance of the rock surface here suggests film formation – it has a darker, shinier surface compared to the surrounding rock. Perhaps this is promoted by moisture running down the face of the rock.

This film is now known as rock varnish, and it has been widely studied. Its formation is thought to be dependent on inclination and orientation of rock panels, type of substrate, pH conditions, wind, moisture and sunshine, amongst others.

Even at its fastest, such growth amounts to a coat of paint (25-50 microns) every thousand years. So we might expect it to take two to three coats of paint, or two or three thousand years; to cover over the whiteness of drawings at Cochineros.

There are large motifs on the panel which provide a check on consistency in space, that is from left to right across the panel and from top to bottom.

The dot track runs for a length of almost two metres from close to the top to close to the bottom of the panel, and the dots have a consistent brightness (with a large variation) until the lowest seven dots, which are also smaller. Similarly the heart extends across 60 cm horizontally and vertically, and appears consistently bright. The white band at the foot of the panel is unbroken, which suggests there are no vertical areas with differential film formation.

On the other hand, the top and shoulder of the rock, and the upstream facing panels, seem to offer different conditions for rock varnish formation as can be seen from their patina.

The linear fit simply assumes that if the image brightness falls, for example, by 20, from 220 to 200, in 400 years, then it will fall by five times as much, from 220 to 120, in 2000 years. In fact if the darkening is caused by a film which grows at a constant rate of say four microns every hundred years, the relationship would be exponential. That means if it falls by 10%, from 220 to 200, in 400 years, it will fall by 10% plus 10% plus 10% plus 10% in 2000 years. So the brightness will fade to 90% to 81% to 74% to 62.5% (or to 137 pixel value) rather than 50%. This makes little difference to the ages of the brighter images such as tupus, but suggests the darkest figures could be a few hundred years older. As an example, the exponential plot for one of the images 4606.cr2, is shown below. The Spiral behind the 1964 still dates to 1400 BP or 600 AD, but the dark figures may be pushed back to 100-200 AD.

If the film forms at a constant rate with time then the fit would be exponential. Rock varnish formation is thought to depend on climatic conditions – temperature, humidity, and wind. These conditions would not have changed greatly over just a few thousand years, prior to the spanish invasion and the destruction of the environment that followed.

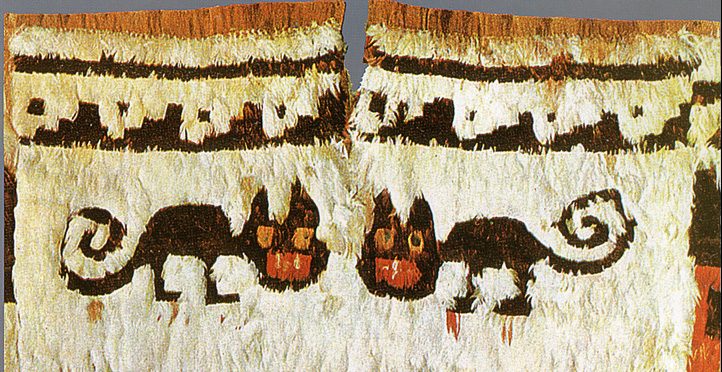

Many drawings on other panels recall Chancay-style textile or Late Horizon images.

There are engravings of sea-birds which are similar to Chancay or Chimu textile imagery found at Pachacamac, from 1000 to 1470 CE. A pair of felines close to ground level on Piedra 9 also resembles Chancay woven textile designs. There are birds flying over the shoulder of Piedra 1 which recall Ychsma (1100 to 1470 CE) ceramics.

These drawings are not on the dated panel, and so the comparison is only qualitative, but they are clearly visible bright images, and they can be assigned stylistically to the Late Intermediate or 1000 to 550 years BP.

Another confirmation of the dating comes from the main tableau of the panel which shows several lake figures reaching up to peak outlined with jagged lines, and the dot track and related figures climbing upwards. If these motifs represent Paria Caca and related rituals such as annual pilgrimage (the dot track) and llama sacrifice, then their dates should agree with what we know of that.

A clue here is the alleged age of Tutay Quiri, founding father of Huarochiri and the Checa, whose mummified remains were taken to Lima in 1611 to be publicly burnt as a gesture of destructive contempt for everything Peruvian. Jesuit Acosta was told by the Peruvians that he was more than 800 years old (another source says 600 years old). If this date is reliable, then Paria Caca’s presence in the mountains and valley may date from 800 CE through to, say, the extirpation of the idolatries around 1620.

The proposed dates from the brightness measurements put the lake deities at around 1000 CE, whilst the dot track and associated figures that may be holding llamas date to the early years of the Spanish invasion. I feel that there was an older original dot track, contemporary with the horizontal tracks, which was refurbished, with new figures added, in Inca or spanish times.

But at the further end of the brightness and time scale, there are the dark images – those that do not appear as white marks on the black stone surface. On this panel, these include a trumpet player, a complex dark figure, and other marks. They do not appear to relate to the Paria Caca imagery, and they are mostly purely abstract.

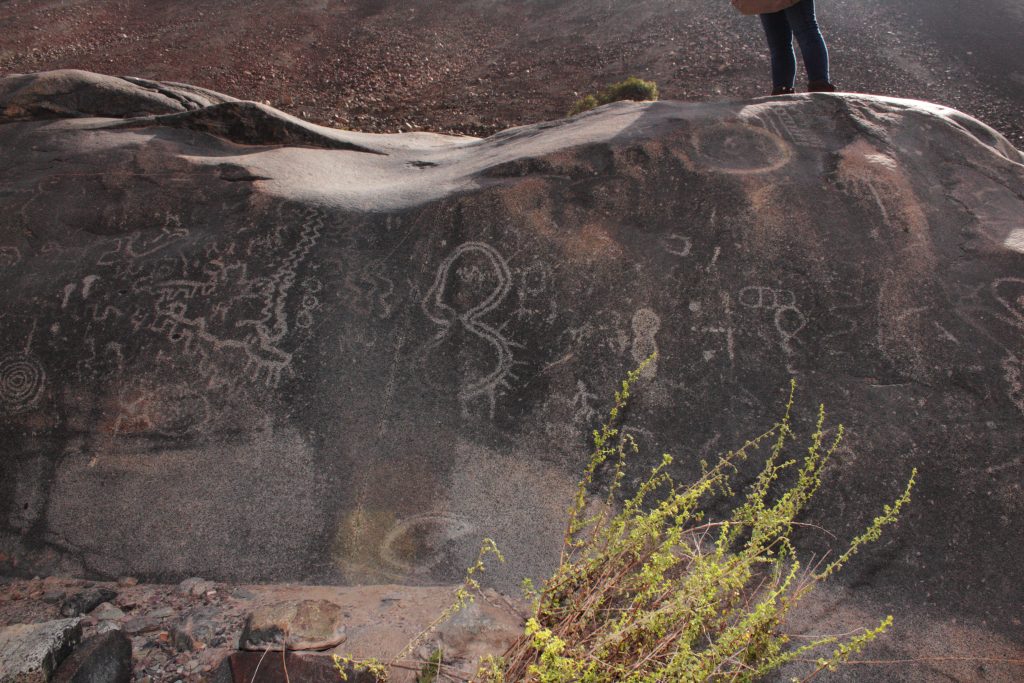

These dark images are almost invisible for someone walking amongst the stones under a bright midday sun (Figure 10). But when I position myself to see the sun close to the June solstice reflecting off the slanting southern face of Piedra 12, the hidden engravings stand out dark and clear against the shining rock surface (Figure 11). The motifs show up even more clearly when the image is stretched to account for perspective (Figure 12).

The sloping faces of Piedra 12 have at least thirty dark images. A few bright images – llamas, foxes – have been drawn over them. These dark images are also drawn on other rocks at Cochineros. But they were mostly not recorded by Antonio Jimenez because without the fortuitous angles of the late June sunlight slanting off the rocks they are very difficult to see.

The majority of these images are abstract and geometrical, including parallel lines, curves and dots. There is little or no repetition. They are deeply inscribed, and evident from the surface depression or change of texture rather than colour change. On the estimated time scales above, they may date to 1500 to 2000 years BP or earlier.

These dates would include the period of Wari presence on the central coast, but there is nothing in the motifs on the rock that suggests Wari influence. However, Lima culture (1700-1200 BP) ceramic styles were also geometric, in contrast with the Late Intermediate Chimu/Chancay/Ychsma figurative motifs of camelids, birds and felines.

This site has been used as a drawing board for close to two thousand years. Complex abstract imagery dating to between 1000 and 2000 BP has been overwritten by more recent figurative images of birds, llamas, fish, tupus and tumis from 1000 to 500 BP. Several phases of drawing are evident, and there is scope for much more detailed study.