There are more than 1000 elements pecked or scratched into 20 boulders at the petroglyph site of Cochineros, on the banks of the Rio Mala in central Peru. Many, perhaps, most, are abstract. It is difficult if not impossible to know now what they represent. But some are figurative – they are clearly fish, birds, camelids, dogs, or human figures, or shawl pins and sacrificial knives. We still don’t know what they represent, but at least we have the first clue. And there are some apparent rules about how these objects are depicted.

Human figures stand upright on vertical or steeply sloping rock faces. Birds fly upwards or over the shoulder of the rock. Groups of llamas walk in horizontal lines. Those lines are positioned at ground level, or traversing natural ridges of the rock surface, as if on mountain paths. Serpent-rivers, long wavy lines, run downhill towards the ground and the river. Rayed circles, which might represent suns or stars, are drawn on the peaks of stones or on near horizontal surfaces facing the sky.

Images of living creatures respect the horizontals and the verticals. Many of the images on the panels at Cocineros appear to be positioned in a mystic world where the rock represents a landscape.

This generalisation seems to apply to the figurative or representational engravings, which appear to be more recent. It is not clear if the dark, abstract images might also link to the landscape since in most cases we do not know what they represent.

The mountains of the Andes are the source of life-giving waters, as well as terrifying huaicos and floods, and they are the homes of gods. The Moche sacrificed girls on a mountain top, and depicted the bloody ceremony in in their ceramics. Children sacrificed by the Inca, including Juanita, the Ice Princess, have been found buried under the snows on the peaks of Ampato, Pichu Pichu, Sara Sara, and El Misti. The people of the Huarochiri Manuscript raced their llamas to the tops of the mountains at the annual festival time. And today, ten thousand people of the sierrra walk for three days to climb Ausungate in late June, dressed as bears and playing drums and flutes, for Quoyllur Rit’i, the Festival of the Snow Star.

Looking up from the river, it is easy enough to see some of the Cochineros rocks as mountains, since the largest are four metres high. But the land is terraced up from the river, and the ground above can be level with the top of the rock. Only two large rocks stand above the ground from whichever side they are approached.

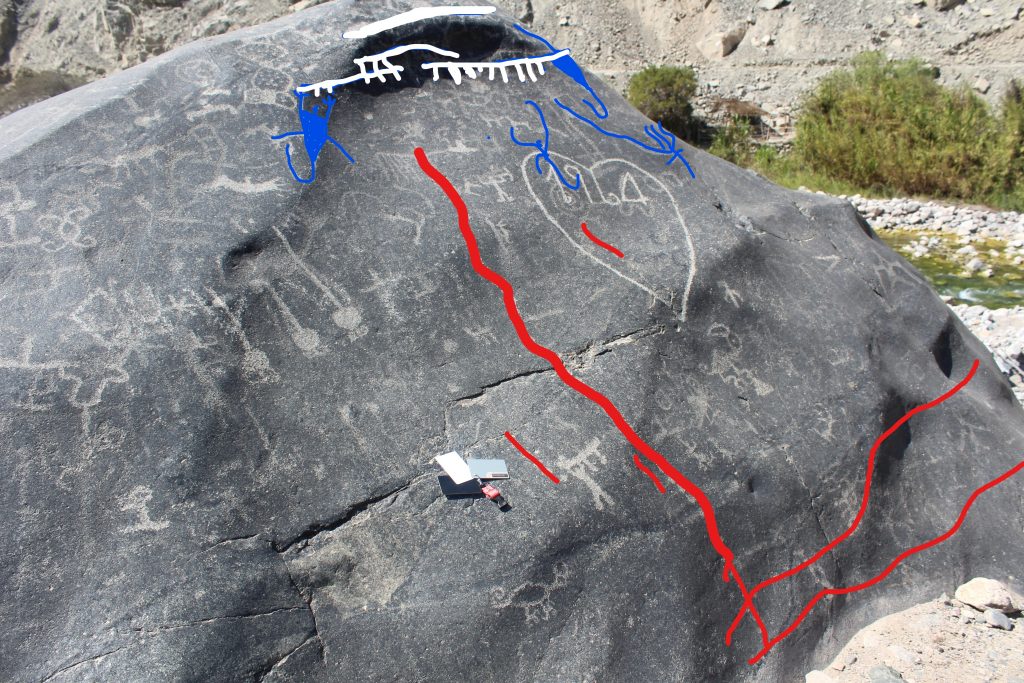

One of these rises steeply to a peak from whichever side it is viewed (Figure 1). The peak is two metres above ground level from the west and four or five metres above the banks of the river on the east. It naturally appears as a metaphorical mountain.

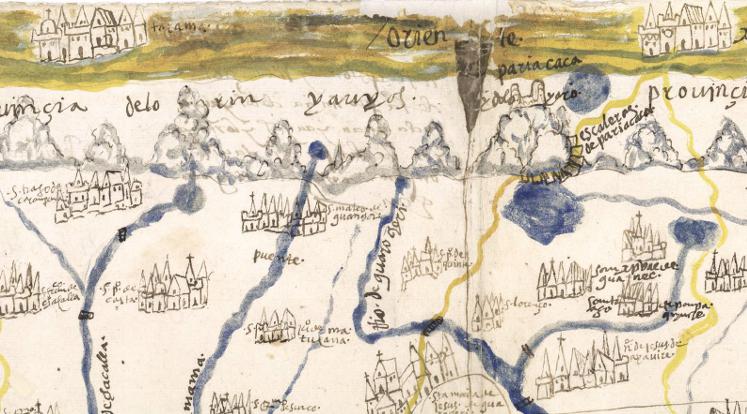

The mountain range of Paria Caca, the central deity of the Huarochiri Manuscript, has a prominent twin peak when seen from the south on the approach from Tanta (Figure 2). This double peak is an important aspect of the mountain as an idol; small cairns, or apachetas, set up by pilgrims and travellers besides the historic pathway towards the mountains are double cairns.

Paria Caca is a founder ancestor who rules and roams from the mountain peaks down towards the coast. But his home ground is in or around the mountain peaks above the glaciers, lakes and streams that become the rivers Rimac, Mala, and Guarco or Cañete (to use their modern coastal names) running to the sea. He appears to have been particularly associated with the twin peak, but his major shrine is somewhere below.

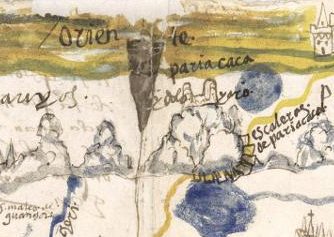

The representation of the mountain labelled “Paria Caca Ydolo Yaro” on a 1586 map drawn for the first Corregidor of the Province of Yauyos clearly shows two peaks (Figure 3).

An adobe frieze with a repeated image that might represent the double peak of Paria Caca (Figure 4) runs along the top of a high wall surrounding an open square at the archaeological site of Huaycan de Cieneguilla. The remains of this Ichsma and later Inca town are in the Cieneguilla valley besides the route from Pachacamac to Paria Caca. The frieze, which runs around three sides of a patio, also shows circles and a feline.

Seen from the river, Piedra 11 has two prominent peaks (Figure 5). There is a large and finely drawn figure below the right hand peak, similar to a Chimu crescent headdress deity. A second dominant anthropomorph is drawn towards the top of the left hand peak, on the southern face.

This rock, on the southern face, is topped by a fringe of short vertical lines (Figure 7). This fringe is held up aloft at one end by a creature with a broad body and round head, outstretched arms, a fox head belt and curving tail. A similar creature is drawn at the opposite end of the fringe (Figure 8). Faintly visible in the centre of the panel, close to the spiral, is a third such creature.

The mountain heights associated with Paria Caca are snow capped, with a line of peaks, and around the peaks are several lakes fed by the melt water of the glaciers that depend from the peak. On the southern side are Mullococha and Paucarcocha, in the centre is a chain of lakes called Chuspicocha, and on the north are Suyoc and Tototral or Rantao (Figure 9).

Figure 9. The snow capped peaks of Paria Caca, the white peaks surrounded by lakes, as seen in a Google Earth image. The ice melts into lakes whose outlets are the sources of the rivers Rimac, Mala and Guarco. Mullococha marked on the upper right, is smaller than other lakes but is by far the largest on the 1586 map.

The position of the Cocineros site midway between the coast and the highlands, and with a clear view up the valley, makes it easy to envisage these rocks as symbolic mountains. On a clear day an observer can stand before the rocks and look beyond to see white clouds over distant mountains that could be imagined to be snowy summits (Figure 10).

Whilst many of the drawings on the rocks of Cochineros appear to be small individual contributions without an overall theme, the peak of this rock appears to present a tableau which is more than a metre wide (Figure 11).

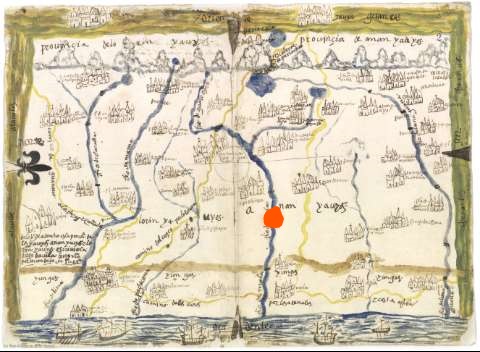

There are similarities to the map prepared in 1586 for Davila Briceño, the Spanish Corregidor of Yauyos (Figure 12). Here the mountains are represented by a series of white peaks in a line at the top of the page. They parallel the sea, a line of blue at the bottom of the map. Rivers are shown as if reaching out arms to the mountains, with the three major rivers being the Rimac descending to Lima, the Rio Mala coming down past the stones of Huancani, in the centre of the map, and the river to present day Cañete on the right hand side. The largest rivers begin from lakes close to the mountains.

The map was prepared in response to a request from King Phillip of Spain for a record of his colonies in 1577 and sent to Spain in Europe 1586. It is interesting that the peak of the mountain is labelled Idolo Yaro and drawn as a shrine. It was then still considered appropriate to mark indigenous religious sites on a map. Twenty-five years later, Francisco de Avila would climb up the mountains with a team of Jesuits to destroy these shrines.

It is not a realistic map. The size of the rivers and the lakes is exaggerated. The largest lake is that shown at the foot of the Idol. The Escaleras, the Stairs, of Paria Caca pass right by it (Figure 13). But this lake, Mullococha, is just two kilometres long and half a kilometre wide. Nearby there is a chain of four lakes, eight kilometres long, Chuspicocha, that is barely shown on the map.

Perhaps the difference is that Mullococha, small in size, looms large in the myth of the area. It was here that the battle between Paria Caca and the old god, Huallallo Caruincho, was fought. The lake itself was created during the battle and played a decisive role in the defeat of the cannibal Huallallo Caruincho.

According to the Huarochiri Manuscript, “From early in the morning to the setting of the sun, Huallallo Caruincho flamed up in the form of a giant fire reaching almost to the heavens, never letting himself be extinguished. And the waters, the rains of Paria Caca, rushed down towards Ura Cocha, the lower lake. Since it wouldn’t have fit in, one of Paria Caca’s five selves (or brothers) knocked down a mountain and dammed the waters from below…nowadays this lake is called Mullococha. As the water filled the lake they almost submerged that burning fire…finally Huallallo Caruincho fled toward the low country.”

These aspects of the map – the drawn and labelled idol, the oversized lake, and the staircase – suggest that the map represents the vision of the world of the indigenous people. Barely fifty years after the Spanish arrived in Peru, they used someone with local knowledge to create the map. The similarity between the imagery on the rock and that on the map may be because both represent important realities for the authors, not of geography, but of the position of Paria Caca and Mullococha in their world. At this stage, the invading Spanish were concentrating on taking control of property, land and labour. The Extirpation of the Idolatries, the destruction of indigenous culture, had not yet begun.

The fringe of white lines drawn on Piedra 11’s southern panel could be considered to represent the snow cap and descending glaciers, and the three anthropomorphs below could be seen as personified lakes. They are linked to the snowy peak of the mountain by their arms which are streams of water. Their tails too are the outlets of the lakes, the source of water flowing down the valley. In the real world, the lakes below the peaks have a similar form, wide below the glaciers and then narrowing and curving (Figure 9).

The north facing panel on the other side of the rock does in fact have a small depression that fills with water – a symbolic “lake”. And drawn on the rock leading up to this are a series of 20 horizontal lines that resemble a staircase.

The panel of the Paria Caca rock has a vertical trail of dots, which rises from close to the foot of the rock towards, but not reaching, the fringe across the peak (Figure 14). If the fringe of white lines and its lake-like creatures represent the mountains and the water sources, it would be consistent to see such a line as being a path towards the mountains. At the foot of the rock, parallel to the ground, is another line of dots which runs to left and right. This line of dots would then represent a coastal road, with the ground itself representing the sea.

Other drawings on the panel are consistent with its perception as a mythical mountain. A condor soars high up on the shoulder of the mountain. There are camelids too, on the left hand shoulder of the rock. Swifts fly up from the lowlands.

We are told in the Huarochiri Manuscript, that people from throughout the region used to walk or run to Paria Caca, the twin peaked mountain from where the Rio Mala descends. These people included the Yunca, who had been driven down from the mountains to the coast by the newcomers. The manuscript lists the communities valley by valley heading south.

“But, in the old times, they say that all these people used to go to Paria Caca mountain itself. All the Yunca people from Colli, Carhuayllo, Ruri Cancho, Latim, Huancho Huaylla, Pariacha, Yañac, Chichima, Mama, and all the other Yunca from that river valley (the Rimac); also the Saci Cayo, who together with the Pacha Camac come from another valley (Lurin), and the Caringa and Chilca, and those people who live along the river that flows down from Huaro Cheri, namely the Caranco (Rio Mala), and other Yunca groups who inhabit that river region, used to arrive at Mount Paria Caca itself, coming with their ticti, their coca, and other ritual gear.”

This is a list of settlements in the lower valleys from north to south, including places now absorbed into greater Lima in the Rimac valley (corresponding to the modern names Carabayllo, Lurigancho, Ate, Huaycan de Pariachi), and people whose names are remembered in today’s villages of Sisicaya on the Lurin, the lomas of Caringa, Chilca on the coast and Calango just twelve kilometres downstream from Cochineros on the Rio Mala.

So the people of the Mala valley would have travelled up to Paria Caca at the annual festival in June. They would presumably have travelled along the the narrow trackway which rises and falls along the hillsides of the valley, which rises from La Capilla, 7 km downstream, and later descends to the town of Minay, 5 km upstream. It may be that they passed these stones, and camped and fed their llamas on this broad plateau by the river.

The sloping face of Paria Caca rock might then have been seen as a metaphor for the mountain for passing pilgrims, and the line of dots ascending from close to ground level, to a height of two metres, would represent a path towards the mountain, the pilgrimage route to Paria Caca.

We are told in the Huarochiri Manuscript that after the Spanish came, many people no longer travelled to Paria Caca itself, but to other closer mountains or hilltops. The stone itself could have represented the mountain, at these later times when people gathered by the stones as a proxy for rituals nearer home.

Two figures appear beside the vertical line of dots or path. The upper figure appears to hold a tumi knife and a llama. The lower figure holds aloft something which could also be a llama.

These could be depicting the pilgrimage described in the Huarochiri Manuscript, where “people run a race on their way to this mountain, …driving their llama bucks. The strongest ones even shoulder small llamas. They scramble upwards, each thinking “I mean to get to the summit first!”

And when they reach Paria Caca, “they worship with the sacrifice of a small llama”.

The rock panel has lines of dots close to the present day soil level. Two run towards the river to the right of the panel, and one heads to the left. If these represent coastal roads and were drawn to a consistent scale with the vertical dot track, they would reach to Chancay or Huarmey on the north coast, and Chincha and Huancor to the south. These potential links between shrines to the north and south are compatible with what we know of the pre-Inca central coast.

Although some markings on this rock may represent a conceptual map of the Apu Paria Caca, they were not all made as the same time. Based on measurement of the patina, the lake figures reaching up to the peak, together with the two swifts or swallows on the right and the anthropomorphic figure with strands touching the peak were drawn around 1000 BP. These also share stylistic similarities. They are fully drawn, with clear edges and a uniform interior. The right hand side of the fringes on the peak are done in a similar style but the left hand side, and extra fringes marked above, are less well formed. The horizontal trails, the “coastal roads”, could be a similar date, whilst the top part of the vertical trail of dots and its associated llamas and men, tree climbing cat and condor, were added around 500 BP. It may be that the upper portion of the dot trail and the snow cap were redrawn at that time, highlighting an original from 500 years earlier. These estimates suggest a five hundred year continuity for the Paria Caca cult at this site, which is in line with what we know from the Huarochiri Manuscript.

There are darker images here too. The spiral and serpent figures seen within the modern heart are older images, as you would expect of the drawings in the centre of the panel. These could date to 1500 BP, and precede the Paria Caca tableau.

This interpretation of some of the images on this particular boulder, as representing an identification of the rock with the twin peaked mountain above the shrine to Paria Caca, and by extension with the god Paria Caca himself, would fit with an account of Francisco de Avila’s visit to Yampilla, a league’s distance from Huarochiri, by Mario Polia de Ondegardo (1611) in a letter to the Jesuits describing the work they were doing in Peru.

“Later we climbed a hill nearby where there was a very famous shrine. There were seven very large rocks placed around, which represented several idols, some of them on this bank of the river and some on the other side. The third was to Pachacama, the fourth to Punchau, the fifth to Paria Caca, the sixth to Chaupinamoca, the seventh another idol. There was a priest assigned to the shrine who knew very well the ceremonies and sacrifices that would be carried out at each of the several festivals… “

There are five great rocks here and four less important ones, to judge by their size and designs. If this one rock represents Paria Caca, then other rocks at the site may also have represented ancestors in the highland and coastal network, wives, sisters and brothers, sons and daughters of Paria Caca and Pacha Camac.

Go back to 102c – Five Day Fiesta 3

Go forward to 162b – How old are the engravings?

Siete cartas ineditas del Archivo Romano de

la Compafiia de Jesds (161 1-1613):

huacas, mitos y ritos andino pp213-214

Mario Polia*