Sitting at a simple wooden table in the echoing concrete hall of the National Library in Lima, with an anglepoise lamp at my elbow and fifty silent researchers for company, I discover a long history of art on stone, throughout South America, as long as humans have lived on the continent.

America stretches like a giant semi-colon, the length of the globe. It descends from the frozen Arctic of Canada and Siberia, down through the USA, Texas and Mexico, to the narrowing isthmus of Central America and Panama, before broadening into Colombia and Venezuela, Peru and Brazil, Chile, Argentina and Patagonia, ending in the icy Antarctic.

People from South America can be touchy when citizens of the USA talk about America as if it runs from Montana to Texas and Maine to Florida.

This continent was the New World not just for European invaders but for all mankind: humans did not step foot here until some 20,000 years ago. Towards the end of the Ice Age, a small group of people crossed Arctic wastes from Asia. They then rapidly spread throughout the entire region, over a few thousand years.

So the indigenous peoples of North and South America are tightly related. They look similar, from the Inuit in Canada to the Comanche in Texas and the Mapuche in Chile, via Amazon and Andino natives, and they have similar customs. Wearing their hair in braids, carrying their children tightly wrapped in a papoose, and drawing pictures on rocks.

It began very early. In the cave of the Toca de Boquairoa de Pedra Furado, in the North East of Brazil, there is the earliest known rock art in South America. A fragment of stone with two parallel lines painted in red was found under a hearth whose upper level was dated to 17,000 years BP, Before Present.

Other paintings visible in the shelter today might be 8000 BP. When the first maize and squash were being domesticated in Mexico, animals, humans and geometrical figures were being painted on rock shelters in the lowlands of Brazil and Argentina, and in the Southern Andes of Chile and Bolivia. A few thousand years later, scenes of humans hunting camelids appear in Patagonia. In Peru there are painted scenes of pregnant camelids and hunting which may be of a similar age.

Engraved rock art in Peru, designs scratched or pounded into the rock surface, came later than the paintings. Some of the earliest can be stylistically related to Chavin imagery, dated to 3500 BP. Other engravings reflect Paracas culture, 3000-2000 BP, Wari from 1300 to 1000 BP, and Chimu, 1000 to 600 BP. Sites often contain dozens of rock panels and hundreds of engravings. The paintings, mostly in highland rock shelters, were probably created by hunter-gatherers, or pastoral nomads. The engravings, on the other hand, are largely in the coastal valleys, perhaps reflecting the evolution of settled farming on irrigated land.

The petroglyphs at Cochineros were best studied by Antonio Nuñez Jímenez, a Cuban adventurer and revolutionary. As Cultural Ambassador to Peru, from 1972 to 1978, he travelled the length of the country visiting and recording petroglyphs, and published the results in four volumes.

It is an awesome work, but has the flaws that might be expected when someone aims to do the impossible in half the time, whilst attending embassy dinners. The complete work was published in 1986, ten years after he visited most of the sites. I can imagine him working through a pile of notes, sketches and photographs which he had assembled over several years, transported back to Cuba in bundles, and finally laid out to compile into the first ever record of Peruvian engraved rock art.

Petroglifos del Perú records the stones of Cochineros with 36 pages of drawings and photographs on stones numbered up to twelve. The numbering of rocks is confused, and some important panels are missed, but what Nuñez gives us is almost entirely accurate. His drawings includes a scale and a description of the panel for many images, as well as the relative position of some stones. He chose a system of recording the images, outlining them in chalk and then tracing them onto paper, which he applied consistently across the country. However, it has one big flaw. It does not distinguish between images with different patinas.

Other researchers visiting the site have attempted to catalogue the images or map the position of the stones, but have been defeated by the scale of the task. Nuñez’ twelve stones became fourteen and eighteen, but what is more interesting is the complexity, the depth of the site.

The work is long out of print, but I find a helpful librarian who tracks down the volumes in this giant building of concrete and hushed rooms. I fill out a slip at the counter, and a few minutes later Volume One is brought to me. At my plain table with a side lamp I pore over page after page of black line drawings. There are large complex figures, fanged heads with snake-hair appendages, hooded eyes, wide nostrils. as I turn the pages I can see similar images, or similar styles, repeating. I ask for Volumes Two and Volume Three, and the representations become simpler with small figures of birds and serpents, circles and spirals, and complex abstract patterns linked by lines. In Volume Four there are still serpents and birds, but now there are felines too, and llamas, single and in groups, with human figures, dancing amongst zigzag patterns and parallel lines.

Nuñez recorded his petroglyphs site by site, from north to south. I appear to be looking at a progression.

The gradual evolution through his four volumes parallels the findings of Jean Guffroy, who published the first attempt to summarise Peruvian rock art in “El Arte Rupeste del Antiguo Peru”.

Guffroy identified three Traditions, with Tradition A, largely based in seven coastal river valleys in the north of the country, being the oldest, 4000 to 2300 BP.

Tradition B is found here but also in the many valleys south to Ica. This more recent style of petroglyphs is considered to date from a little over 2300 years BP, and continue up to the Spanish invasion. The petroglyphs of Mala and Cañete lie towards the southern end of Tradition B.

In the South, from Ica down to Northern Chile, Guffroy identifies a third Tradition C, more recent still, considered to date from 1400 BP up to the invasion.

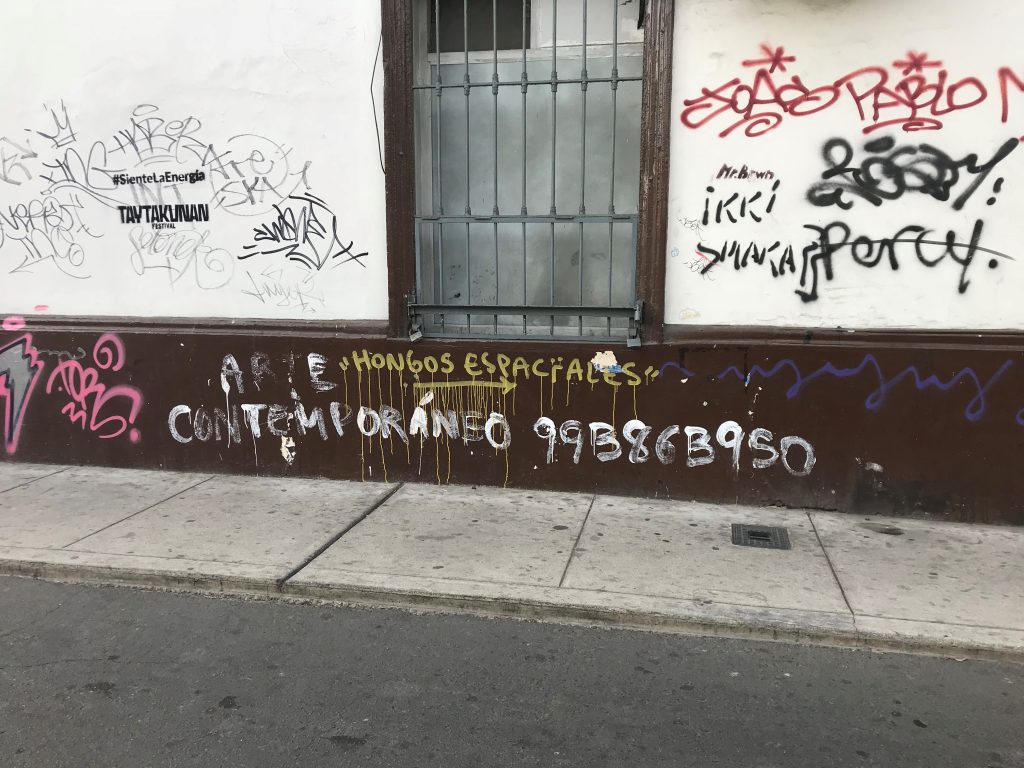

I leave the library and take a combi back to Barranco, walking past “La Noche” to the main square where Venezuelans play electric guitar and violin for small change. For the first time, I look at the layers of graffiti on the walls, at tags repeated along the street, and ask myself why they do what they do.

Go backward to 3. 256 Shades of Grey 2…