I am very curious now about the rituals that might have taken place around the stones. And there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that altered states of consciousness were a part of such rites, for the priests, the participants or both.

I am investigating psychoactive drug use, I tell Mayra. Would she like to join me?

“I have enough craziness to deal with. Give me a call when you have been through rehab,” she says, laughing. And so I head to the library again, on my own.

In a rock shelter above the Matanza river, 15 km from Cusi-Cusi, a small village in north west Argentina, two bodies were found in 1990. The bodies, wrapped in blankets, had been buried with small cylindrical containers, tiny measuring spoons, flat tablets and short narrow tubes.

Any follower of late 20th century western culture would recognise this – the tubes of choice in the 1990s were rolled up hundred dollar bills, or twenty pound notes, the flat surface was a mirror, cocaine spoons were made of silver, and the little cylinder was replaced by a plastic bag. The spoons, tubes and tablets look like drug paraphernalia.

But these bodies were mummified and buried at the back of a cave. They had skull deformations. Their blankets were of fine alpaca, the tablets were carved in stone and the snuffing tubes were of decorated bone. They were most probably 1000 years old.

Hallucinogens are not new. Such drug paraphernalia – inhaling tubes, tablets, containers and spoons – have been found throughout the area of the Tihuanaco culture, centred on Lake Titicaca high in the Andes, and reaching down to the coast.

Peru is one of the world’s major sources of cocaine – the black humour that helps Peruvians tolerate the corruption of their institutions and the immoral stupidity of their elected leaders, not to mention the brave but ultimately disappointing performances of their national football team, has it that the country is about to become world leader in the drugs trade, stealing the title from Colombia and Mexico. But the coca leaf in its natural form is a mild stimulant. It is used daily by farmers and labourers in the Andean highlands to help them to work in oxygen deprived air thousands of metres above sea level.

The Inca devoted the best farmland, in the warm sunlit river valleys of the Andes, to growing this prized bush. Searching for coca leaves to relieve my soroche, altitude sickness, in Cajamarca at 3000 metres, I found it not in the fruit and vegetable market nor in the pharmacy, but in the hardware store, a great sackful of leaves alongside the bags of cement, roofing sheets and plumbing, a workers’ panacea. I bought an armful of the dry leaves for half a dollar, and probably paid too much.

For the indigenous people of Peru, coca has been a daily stimulant, like tea or coffee in the western world, for thousands of years. For relaxation or ritual they had other substances. In fact a wide variety of drugs were used by different peoples at different times, according to the interpretations of archaeologists.

At the three thousand year old ritual centre of Chavin de Huantar, I walk through an underground maze of narrow tunnels lit by occasional skylights to approach El Lanzon, a four metre long pillar of sculptured stone plunging deep into the earth and reaching up to the sky. It is illuminated in the darkness by sunlight from a hole in the roof above. Some archaeologists believe that sacrificial blood was poured over the shaft from the roof hole, to drip down the grooves in the carven stone.

But my walk through the maze to approach this fanged, clawed, deity is a disturbing enough experience. Sounds echo confusingly around the multiple passages and chambers. A hole opens in the floor in front of me, looking down on lower rooms and corridors. I treasure my face-to-face with El Lanzon, but I am glad to find my way back to the sunlight.

Archaeologists have suggested that the original participants in the maze-walks were a privileged few, wandering under the hallucinogenic influence of San Pedro cactus, perhaps with the sound of conch shell trumpets echoing through the dark stone corridors.

The cactus, Trichocereus spp, is depicted on chavin ceramics and stone carvings, often being carried by healers or shaman figures. There are references from chroniclers such as Fray Bernabe Cobo (in his 1653 Historia del Nuevo Mundo) to a cactus, achuma, which “…drinking the juice of it, it removes their senses, so that it leaves them as if dead…transported, they feel a thousand different things and believe them to be true…”

Much of the iconography of the Chavin centre depicts a man-jaguar hybrid: there is a series of carved heads set in the walls surrounding the New Temple (dated to 2500 years ago, hence the name) which appears to show stages of a transformation from man to jaguar. Some figures show mucus streaming from the nostrils, something considered to be a distinctly Chavin representation of drug use, also seen in adobe reliefs in U-shaped temple mounds in Lima, 1200 kilometres to the south.

The Moche on the northern coast, 1500 years ago, produced red and white ceramics wonderfully decorated with narrative scenes similar to those of the ancient Greeks, highly realistic, showing running figures surrounded by symbolic objects. The content is clear, but the meaning is obscure. Unarmed men carrying bags run in lines through a sandy landscape; variegated patterned beans float in the air around the runners; beans, dressed as warriors, fight with warrior deer; an iguana god and a snake-belt god play a game with beans and sticks; women healers holding San Pedro cactus care for patients or prepare drinks; ulluchu fruit are carried or float in the air above sacrificial rites; individuals or groups take coca with lime; priestly figures with clubs drive deer into a net where there are speared.

After the discovery of dried fruit in a tomb in Sipan, the ulluchu has recently been identified as a fruit of a mahogany species. It may have produced increased blood pressure and heart rate, it could have been an aphrodisiac or used to provide a more bloody and spectacular sacrifice. It may also have been used as an hallucinogen.

The deer hunt is one of the events frequently portrayed on Moche ceramics, a ritual or a seasonal event when the winter sea mist brings moisture to the lomas, the low hills close to the coast, so that the brown desert becomes covered with succulent green flowering plants. Animals and pastoral herders move down from the heights to enjoy the pasture, as happens today in the hills around Lima. Such hunts would thus mark the passing of the seasons. A plant shown in some deer hunt scenes is thought by some to represent Vilca, Anadenanthera colubrina, whose dried and roasted seeds appear to have been used as a snuff by people nearly 2000 kilometres to the south.

San Pedro de Atacama is a large oasis in the Atacama desert, 2450 meters above sea level, which was occupied by a succession of pre-ceramic hunters and gatherers and ceramic-stage agriculturists and herders. The dry environment preserves textiles, bone and wooden artefacts, and mummifies human remains. It has also preserved hundreds of snuff kits, tidy collections of tools for preparing and delivering nasally inhaled drugs.

Over six hundred of these kits have been found in excavations at around fifty sites in San Pedro. Bodies are typically buried with all or several of a wooden rectangular snuff tray, a snuffing tube made of wood or bone, a spoon or spatula, a small mortar and pestle, and one or more leather pouches used as containers for the snuff powder, often all stored together in a woollen bag. This was not just a priestly ceremony: these findings are so common in burials that more than one fifth of the adult male population appears to have been using psychoactive snuffs from 200-900 AD. But after the tenth century AD, the practice of snuffing practically disappears in the area.

Snuff trays have been found as far north as northern Colombia and as far south as Argentina and southern Chile. The oldest trays and tubes were excavated on the north and central coasts of Peru and have been dated to circa 1200 BC. The habit was widespread in time and space.

Two samples of snuff powders from San Pedro de Atacama have been found to contain DMT and bufotenine, which suggests Anadenanthera species. Small cloth bags containing Anadenanthera seeds were also found at the same site.

There are two known species of Anadenanthera, colubrina and peregrina. In both cases a snuff is prepared from the roasted seeds or beans found in the long pods of the trees. Yopo, from the latter tree, is used today by Amazon indians such as the Yanomami who blow the powder into each others’ nostrils through long tubes. It may be the same as cohoba, a snuff which Spanish chronicler Ovideo y Valdes described being used by the Taino people in the Caribbean in the sixteenth century. The former tree, colubrina, is native to the southern Andes. It is likely to be the source of the snuff used by the people of St Pedro de Atacama. This snuff is still used today by indigenous indians who live in the forests between Argentina and Paraguay. Vilca is a common component of family names (Chumbivilca), towns and religious sites (Vilcabamba). The seed is also known as Cebil, and is said to have been used by the Incas.

The second best known psychoactive drug of Latin America is widely used today, primarily by peoples in the Amazon but also by drug curious tourists who pay in dollars to drink a brew based on the Banisteriopsis caapi vine. The Ayahuasca ceremony is traditional for people in the Amazon but many of the “treatment centres” are owned or managed by people from outside Peru. Several thousand outsiders try Ayahuasca every year, and most years a tourist dies.

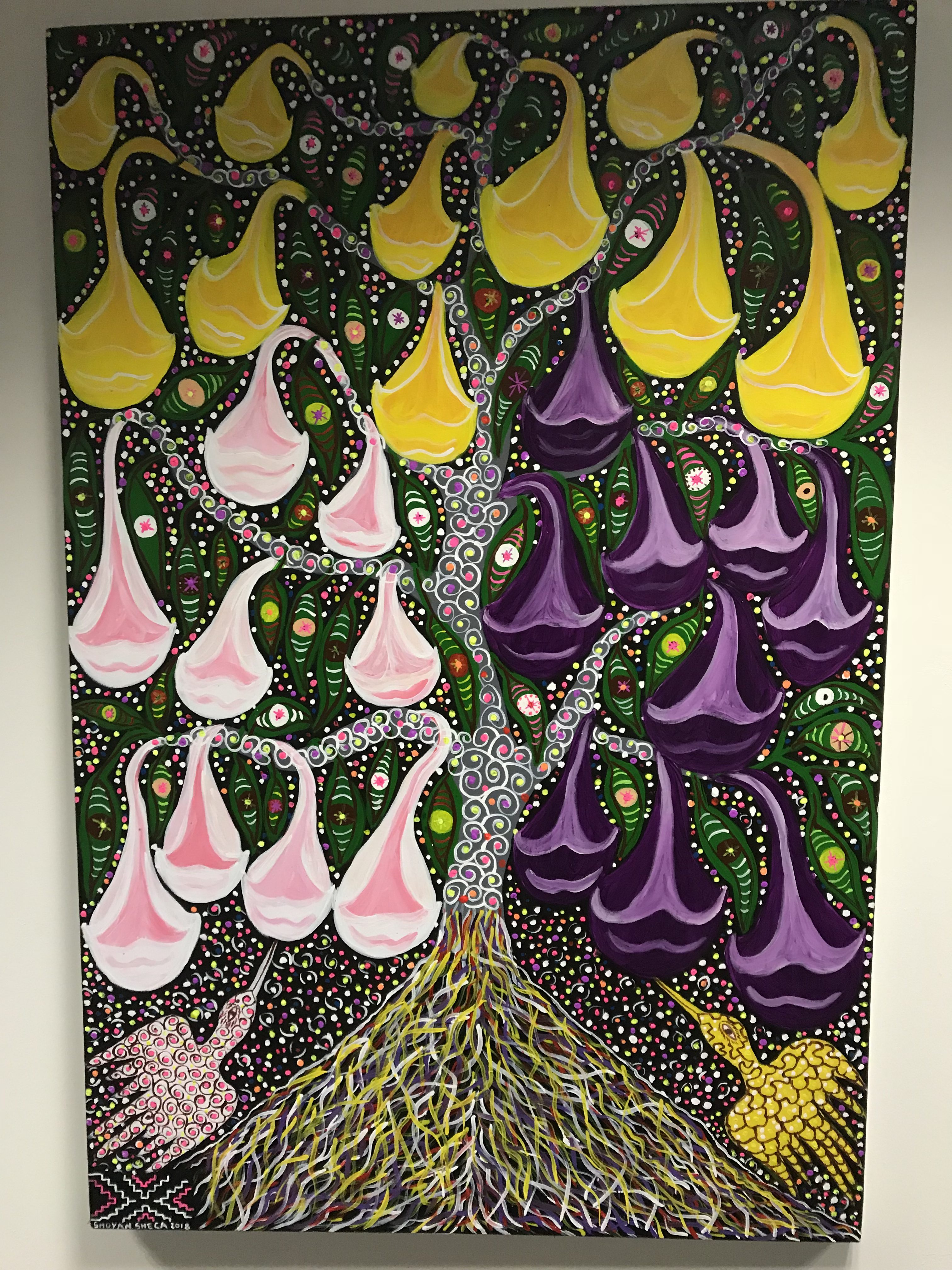

Unlike the Yanomami who remain a people in isolation, users of Ayahuasca include the Shipibo Conibo, some of whom live and work in cities like Lima, seeking a third way to control their future with access to a modern education for their children, whilst still maintaining their own culture. Many sell paintings or embroideries, and zhe Ayahuasca vine and visionary scenes are frequently depicted. Ayahuasca, vilca, and cohoba all contain DiMethylTryptamine, DMT:San Pedro cactus or achuma contains mescalin, like peyote, the cactus buttons collected and consumed by the Huichol people in modern Mexico on their annual pilgrimage.

Espingo is a fruit or seed mentioned by Pedro de Arriaga, who collected information about indigenous beliefs, traditions and values in order to destroy them.

“The espingo is a dry small fruit similar to the round almond…they bring it from Chechepoyas [Chachapoyas – tropical forest regions of northern Peru]. They say that it …is a very effective medicine against stomach aches, bloody diarrhoea, and other diseases, taken as a powder …”

It was, Arriaga explains, an important offering and was also drunk by the priests, with powerful effect.

“In the plains from Chancay and downriver the chicha that they offer to the huacas is known as yale. It is made from zora [malted maize] mixed with chewed maize and has espingo powder added to it…it is made very strong and thick, and after having poured it appropriately over the huaca, the wizards drink the rest and go completely crazy…”

The origin of this fruit is still uncertain but de Arriaga further tells us that “In the plains there is no-one with a shrine that does not have espingo… the Lord Archbishop forbade the sale … for he knew that it was a common offering at the huacas.” If the Archbishop wanted to eliminate it, then it was clearly an important aspect of indigenous culture.

The cinnamon tree is called espingo or ishpingu in Ecaudor and Peru. A careful reading of Arriaga may suggest that a scented spice was added to chicha in Chancay, and that it was the chicha, not the spice, that made the priests crazy.

Brown oval seeds one to two centimetres long, cut in half longitudinally, and sometimes centrally holed and strung together, have been found in Ychsma offerings at Pachacamac and in the Lurin valley. Tests show them to be Nectandra. In Pachacamac the strong smelling seeds are often found within the cloths binding the mummified corpse.

The same seeds are common as offerings in northern and central Peru. They have been found inside Spondylus shells at coastal excavations at the Moche ritual centres Huaca del Sol and Huaca de la Luna, near present day Trujillo. It may be these seeds that are shown on Moche ceramics being worn as necklaces or carried on strings, by priests or anthropomorphic figures with characteristics of the decapitator god Aia-paec.

These Nectandra are said to be sold today under the names amala or hamala by herbalists in central Peru, or as matuc or matuto further to the north. Tests show they have muscle relaxant, pain-killing and anti-clotting effects. Some believe that hamala is the seed that chroniclers referred to as espingo.

*************************************************************

I am living now in Barranco, the “Rive Gauche”, the Soho or the Campden Lock of Lima. A musician living in the flat below me has lively parties most weekends. The sounds of Led Zepellin, classical piano or Argentino tango drift up to my windows, while his friends play their instruments and sing along.

In the gardens I see a knee high, finger thin San Pedro cactus, perhaps the hallucinogen of choice for those who walk the underground maze to the sound of conch shell trumpets to visit the Lanzon at Chavin de Huantar.

On the main street of Barranco I find a shop of religious icons. It sells multi coloured candles and plaster figures of saints. There is a glass cabinet filled with herbal remedies, and the shop provides tarot readings. There is a shelf of aloe vera succulents, whose fleshy green swords are often seen hanging over the doorways of houses and on the walls of shops, as well as from the driving mirrors of combis, public transport minivans. The plant brings good luck, and protects the house or bus from evil spirits. A box by the doorway holds more paganism – horseshoes, a small San Pedro cactus, and slices of several other cacti, roots and plants.

Walking through Barranco towards the main square, I pass the fashionable Ayahuasca bar, a converted colonial Lima house. The front gateway opens onto a yard with an elegant twin staircase leading up to an eighteenth century mansion with high ceilinged rooms, now converted into individually styled social spaces. Each room has a themed design – draped textiles, cork walls, shelves of back-lit coloured glassware. Charming and attentive waiters proffer stylishly served Mojitos, Chilcanos, and Margaritas. It is a wonderful bar, but there is no ayahuasca here.

Crossing the bridge over the Bajada del Baños, the Bathers Descent, looking down on the student photographers posing their girlfriends in front of the characteristic murals of Jade Rivera, a graffiti artist who now has a shop selling cards, mugs and prints just under the bridge, I see a cluster of bell shaped flowers hanging from a low tree in the park. This is Brugmansia, commonly known as Angel’s Trumpet for its pendulous white or yellow display, widely seen throughout Lima streets and gardens. Its leaves and seeds contain several alkaloids whose effects include hallucination and muscle paralysis, and it is said to be used in some Ayahuasca preparations.

A related genus, Datura, shares the same alkaloid mix and has a spiky round fruit. Datura is a Hindi word translating as thorn-apple, and in Europe it was considered, together with mandrake and deadly nightshade, as a ingredient in witches’ brews. I have seen the plant growing by the roadside as I walk from Barranco to Surco.

Outside the abandoned and crumbling hermit’s church three violinists play together, the Venezuelano diaspora, fleeing from a country drowning in inflation.

Walking down the Bajada del Baños, I see the tall old trees surviving in a coastal desert climate that reveal this former fisherman’s pathway as the route of a stream flowing to the sea. The discreet cross at the side of the path, mounted on a three layered pedestal, represents the Andino cosmos of condor, puma and serpent, the over world, the human world and the underworld. It is another hint that this was once a waterway. A woman with three bags of plastic bottles, collected from the beach, stops to touch the plinth and cross herself. She will sell the bottles for recycling, a few cents each bottle.

Red and black spiders hang from threads, and blue and yellow snakes twist along the branches of Brugmansia at the side of the path where a dreadlocked trader displays his wares. He has a collection of pipes carved in soapstone and driftwood. At night, he sleeps on the beach with travellers from Ecuador, Argentina, and Colombia.

A stream of people funnels up and down the paved walkway, between the beach and the Metro station. On either side are restaurants with wooden porches, terraced gardens climbing the hillside, decaying hostels, narrow flower beds. Later the cast iron lamps with their three white globes will light, as the crowds head to the restaurants that look down on the lane for anticuchos, grilled kebabs of marinated sliced cow’s heart, or to the historic bars – Piselli’s, Juanito’s – where guitarists walk from table to table playing songs of the sierra, the costa and the selva.

********************************************************

The next day I take a train into Gamarra in the dirty heart of Lima. Flashing by the windows are freeze frames of a vibrant recycling industry, back yards stacked six deep with fridges and freezers, giant containers of plastic bottles, stacks of doors and windows. The streets are piled with rubbish, packing cases, bruised and discoloured vegetables. Street dwellers, thin and dirty, dressed in soiled clothing, pick through the piles of rotten food at the side of the vegetable market.

Gamarra is a disordered, “informal”, district, poor and dirty, housing a thriving black economy. The garment industry here is said to be worth $1.4 billion dollars annually, and includes 20,000 shops, clothing manufacturers and retailers, employing over 100 thousand people.

I am already a regular visitor to the Gamarra Pulgas or Flea Market, where on a Sunday several blocks of La Victoria present a market of second hand goods, sourced from the trash thrown out by the richer neighbourhoods. On the streets of La Molina or San Isidro, I see “recyclers” searching through the black plastic sacks left out each night on the street corners, collecting all the glass and plastic bottles. From time to time they find something better. So once a week I find a tennis racket with a few broken strings, a pair of binoculars with one working eyepiece, motors and magnets stripped from old computers, phone chargers, cuddly toys, roller skates. I squeeze through narrow alleys between tables piled with mixed goods and then the street opens out and there are old shoes laid out on a blanket, tattered magazines, military medals, pairs of spectacles. Where the back streets cross there are carts selling ceviche, fish soused in lime juice, and picarones, deep fried donut rings whose origins lie in north Africa. People sit under the sun on red plastic chairs eating whilst crowds of shoppers squeeze past them.

On this Saturday afternoon the streets of Gamarra are thronged with sellers, some with goods in shopping trolleys, others spread out on the pavement or on wooden carts. Besides the raised railway that cuts through the centre of the district are vendors of clothing, mobile phones, fruit and vegetables, and cactus. Not cactus to put in a pot on your desk, but great fleshy lobes and columns of white and green. Now I am near the “witches market”, or the herbal medicine area. It has a little of everything. At the front, on the street, are people selling snake fat in little pots, with a few snakes draped over the stand to prove it is authentic. Nearby, a stall has thick yellow fat, looking like vaseline, mounded up in a turtle shell. Just inside the entrance a stall is advertising “Sapos Vivos”, live frogs, and there they are, crawling over each other in a glass case. On the floor a small girl is transferring handfuls of the frogs from a shopping bag into a cardboard box.

The rest of this stall looks like a juice bar, with blenders or liquidadors, and various coloured juices in jugs. A customer with a sore throat arrives. The patron reaches into the glass case and pulls out a couple of struggling frogs, dropping them into the blender with a little honey to whip up a tasty pinkish-green remedy.

I pass on this and go further in. There are stalls piled with religious icons, many with a spanish Catholic timbre, the tin hearts, legs, crosses and medals that supplicants nail to the walls of shrines. There are coloured candles and statues of saints, but there are also, further back or higher up, strands of red and black beads from the jungle, swords with death’s head handles, snake skins and horses’ jaws, wooden masks, bottles of macerating herbs and roots, stuffed armadillos and parrot wings. My eyes are drawn beyond the glass cases of medallions and statuettes to the shadows beyond, and I see monkey and puma heads, insects in glass globes, rows of labelled candles; “Candle for abundance, prosperity and progress”, “Candle of strong garlic against witchcraft and sorcery”, and of course “Candle to give power over love”.

But I have come for none of those, and the search for hallucinogenic drugs takes me further back, where more orderly stalls have stacked shelves and sackfuls of herbs. There is a large carton of San Pedro cactus, and a mixed box of smaller, prickly cactus, six different varieties, with slices of root, of bamboo and of cane. Another has the promising sign “Natural Products of the Coast, the Highlands and the Jungle – including Seeds, Leaves, Branches, Roots and Bark”.

I buy 200 grams of Flor Jamaica, as it is known in Mexico and Peru, or sorrel, as it is known in the Caribbean – a fleshy red flower, which soaked in water releases a bright red colour and a sharp fresh flavour like blackcurrant. As the thin man weighs and bags it I look around at his other sackfuls. Uña de Gato, Cats Claws, Flor de Arena.

“Nothing more” I reply, then spot a box on the floor of the neighbouring stall. “What are these?”

They are mushrooms, a deep brown, dried, with long stalks and round heads stippled with depressions or dots. They are not Suillus luteus, the European edible wild mushroom most commonly seen in Lima, one or two packed with bay leaves as flavourings for a stew. That bolete lives in symbiosis with the imported pines used to reforest hillsides in the Sierra against erosion, and has flourished in its new Andean environment, spawning a thriving industry exporting dried edibles to Europe.

But this mushroom with its spotted cap resembles those seen on Moche ceramics, of shamen or curanderos with mushrooms growing out of their heads. It is a medicine, the man tells me, for male problems. Soak it in a bottle of wine and drink a glass every day. I thank him and buy myself a sample.

Outside Surquillo Market No 1, I had previously had a woman offering me “coca, heroin, cocaine”. This time the same woman appears to have a more formal array of “health products”. Including maca, a root grown in the highlands. This is usually sold either as the dried root or in powder form, and is highly prized in China for its health benefits. Export of the live plant is forbidden. Chinese traders buy fresh tubers in Junin and smuggle them through Bolivia and so back home.

“Coca” she calls to me, as if this was of most interest to gringos. I spot instead a plastic packet of a powder, with a picture of a cactus on the front and labelled “San Pedro Cactus”.

“What`s this?” I ask.

“It’s a cactus”.

“And what do you use if for?”

“It’s a plant that grows here in Peru”

“What do you do with it?”

” It costs 10 soles.”

And so I part with my ten soles for 200 grammes of dehydrated San Pedro cactus powder. The instructions are on the packet.

**************************************************+

My first visit to the Medicinal Plant market has not been a success. I do not know what I am looking for, and I do not know what it is called. So I go back to searching the academic papers about historic drug use in and around Peru.

Huilca or Vilca was said to be the Inca or Quechua name of Anadenanthera colubrina, taken as snuff by the Atacama travellers. Another hallucinogen from a tree of the same species, Adananthera peregrina, was known as Cebil, Yopo, or Cohuba, and was used in the Caribbean and the Brazilian Amazon, further north. Yopo is still used as a powerful snuff by the indigenous Yanomami of the Venezuelan Orinoco. Vilca is also used to refer to a different tree, Acacia visco, further south. The tree is called Vilca, Vilco, Visco, Viscol in Chile and Argentina where it thrives.

The seeds of the two Vilca trees look similar and both appear to contain bufotenine, though the concentration is much smaller in the Acacia. The word Vilca may denote sacredness, status, sanctuary or shrine – it is a word which has a wider meaning than one plant, and could be interpreted as spirit power or holy lord.

Espingo is the scented seed or nut, described by Arriaga, powdered into Chicha by the huaca priests of Chancay. Perhaps it is from the wild cinnamon tree, Ocotea quixos, also called the Amazonian Canela, used to flavour classic Peruvian dishes such as mazamorra morada, a purple maize pudding. The Ishpingu river flows through an area of Amazon forest in Ecuador that was called the Land of Canela – the people that lived there were called Canelos – by the Spanish. Canela is Spanish for cinnamon, but the area is home to a tree whose flowers, leaves and seeds, not bark, have a cinnamon flavour. The leaves are scented but the most common part used is the hard dark base where the seed grows, rather like an acorn cup.

Amala or Hamala is said to be the Moche name for the oval peanut sized seed found in late period burials at Moche ritual centres, and the later Chimu site of Tucume. The seed, one to two centimetres long, has also been found wrapped in the folds of mummy bundles. Archaeologists have speculated that is acts as a muscle relaxant or anticoagulant for the Moche and Chimu sacrificial victims, or as a powerful scent to wrap in the cloths of the dead. It is thought to be a Nectandra species. It might be named Matuto or Matuc further north. It might also have been called Ishpingo by the colonial Spanish.

***************************************

I am searching for two or three plants under eight or nine names. I write all of these down with their spelling variants and visit the mercado de plantas medicinales once again.

Walking past the snake fat salesmen and the displays of cacti, I enter the indoor market and head towards the back end, where the wholesalers have sackfuls of leaves, shoots and roots. Most carry labels, and there are few seeds here. The more religious stalls at the side of the market have small containers of beans, nutmeg, the red and black beans, huayruro, from the selva, amongst the tiny effigies, magnets and pieces of pyrite.

I show my paper to several stallholders without success, until finally one says, with a look of disapproval, “not here. Try that woman!”, pointing.

I approach the stall and and show the hard-eyed woman my paper, explaining “these are all the same thing, a seed, but with different names.”

She looked at the list and read the names.

“No, these are all different. But they are all seeds.”

She strides to a neighbouring booth and walks beyond the sacks of herbs to reach down to a low shelf at the back.

“Vilca”. She hands me a plastic bag of flat, shiny brown seeds.

She reaches down again and brings out another bag. There is a variety of seeds of different sizes and shapes, strung on threads.

“This is espingo, and this amala. Matuc is another thing, it is a flower. Five soles each.”

Amala looks like soft shelled almond with a dark sticky centre. The filling has a sweet fruity smell and the shell flakes away easily. Carmen apologises – she wanted to give me the complete seeds, but they break up as she pulls them from the string.

The ishpingo is a small dark oval seed, not as big as a peanut, which crushes easily. There is a third seed in this bag.

“I`ll take this too. What is it?”

She writes the name down for me, Puchiiin or perhaps Puchuin.

I wonder if she has just sold this gringo any old tosh. But the seeds I have match the images in archaeology papers about findings in Pacha Camac, in Cerro Sechin, in Huaca de la Luna. So there it is. The seeds buried with their slaughtered captives by the Moche, mixed in maize beer and offered to shrines in Chancay, and folded in the cloths wrapping the mummies of Pachacamac and Cieneguilla, are on sale today in Lima, sold in small quantities for ritual use, kept together on a back shelf.

It seems likely that my three strongly scented seeds – amala, puchuin and ispingo – are all nectandra species with hallucinogenic and possibly poisonous effects. They are three of the ingredients of the seven seeds medicine. They are perhaps sold to, and used sparingly by, present day curanderos, healers, and shamans, trance medicine doctors.

The next step, of course, would be to find a curandero to tell me more.