Leaving the Rimac as a broad stream, the Rio Surco threads through Ate Vitarte, San Borja, Surco and Chorillos and splits into side channels which water most of the green areas of the city. Photo courtesy of Javier Lizarzabruru Montani

Running through Ate and Santa Clara, the river`s curving path can still be seen, but for most of its journey it is now encased in concrete.

Waters can be seen running in an open irrigation channel into the Campo de Martes, at the top end of Salaverry, under the tents of the Feria Artesanal and so throughout the park.

Ten million people living on a coastal plain where it never rains – that is the paradox of Lima – the biggest desert city, some say, after Cairo, after Las Vegas. And yet it has two golf courses, a racecourse, an olive grove and vineyards.

Ten million people living on a coastal plain where it never rains – that is the paradox of Lima – the biggest desert city, some say, after Cairo, after Las Vegas. And yet it has two golf courses, a racecourse, an olive grove and vineyards.

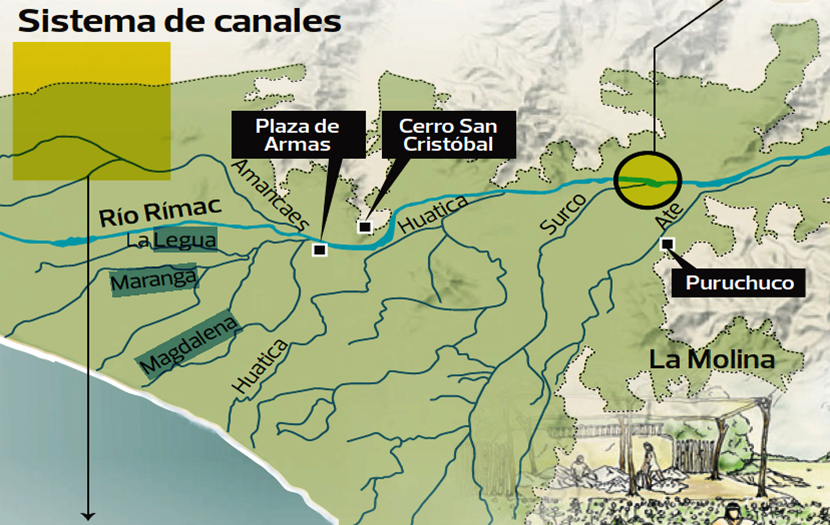

If Google Earth’s timeline could go back a thousand years, it would show us the lands of present day Lima as a plain dotted with hundreds of temple mounds, huacas, surrounded by farmland. Six or more major streams, dividing into streamlets, rivulets and irrigation ditches, take water from the River Rimac to fertile fields and villages from La Molina, San Borja and Surco down to Barranco and Chorrillos, San Isidro and Magdalena, Maranga and Callao.

“The valley of Lima where the city is located, is broad …. this province, like many others, is irrigated by waterways leading from the river, in which there is plentiful water for everyone, and sufficient to fertilise even more land.” Juan López de Velasco, Cosmógrafo de Indias, 1574.

The large parks of Lima – the Parque de los Leyendas, the San Isidro Golf Course, the Jockey race track, Campo de Marte and Bosque el Olivar – are still watered by these ancient canals. The Spanish built their city around the Plaza de Armas where a channel brought water to the several pyramids where now sit the Cathedral and the Presidential Palace. Nineteenth and early twentieth century pictures show the stream that flowed along the Western side of the Plaza de Armas.

Flora Tristan, Gaugin`s aunt, visiting Lima in 1834, wrote “the streets, well delineated, are long and wide. Water runs through two ditches along almost all of them, one on each side. Just a few have a small stream in the centre. At the back of the houses is a kitchen and lodging for the slaves. It never rains.”

On the surface, much has changed. But underground a vast network of channels makes this desert city green, with hundreds of workers managing and adjusting the direction and speed of the flow to take water to each place at the appointed time.

Beside the Rimac in Huachipa is a zoo with a stream flowing through it past the children’s pet centre and the herb garden. Huachipa is fifteen kilometres south of Lima, upriver from Lima’s Plaza de Armas.

The stream, the Rio Lati, flows down behind housing through Ate (to which it gave its name) and past Purochuco-Huaquerones, the Inca administrative centre and cemetery on the Carretera Central where Ate meets La Molina. Puruchuco is 900 years old and the stream delivers water to its very doorstep. The smooth clay bed of the stream together with a complex of stone built walls and conduits could be clearly seen, metres below ground level, when rescue excavations were carried out in 2014. The canal and walls were built over when a tunnel was blasted through the hillside to give faster access from La Molina to a new shopping centre, to be built next to the archaeological site and Patrimonio Cultural de Peru.

The canal, here in a concreted channel, takes water on what was probably its original route behind the 1000 year old ruins of Puruchuco and, shown here, Purachuca.

Several days of the week this Rio Lati rushes down the centre of Separador Industrial, in Mayorazgo, a linear park of grass more than a kilometre long and 70 metres wide. A team of early morning workers stand in the water holding plastic sheeting up to their knees, flooding the expanses of grass on either side, slowly moving downstream spreading the water evenly to trees and flower beds.

On other days, the water is diverted further south past Estadio Monumental and Colegio Alpamayo (here you can see the original centuries old channel circling the hillside above the ruins of PuraChuca), behind the florists in front of the cemetery Jardin de la Paz, and under the road, at a point the combi drivers call the Puente, into the military riding school Centro Hipico Militar, once the country house of President Manuel Prado Ugarteche, where it waters the grounds and feeds the lakes.

Beyond the Centro Hipico it enters the extensive grounds of the Universidad Agraria, irrigating the botanical gardens, the woodland, the campus where alpacas and llamas crop the grass, and the fields where students grow and study maize, quinoa, fruit trees. From here it continues to the golf course Los Incas, and the Lima Polo and Hunt club, mostly covered over and difficult to trace.

In the early 20th century, La Molina was a fertile agricultural area of haciendas – Camacho, Monterrico Chico, Las Hormigas, Las Viñas – with dairy cattle, sugar cane, cotton and maize – all irrigated by the Rio Surco and the Rio Lati. A few years ago sections of Surco flowing through Ate and Santa Anita were still open, but as they became choked with rubbish the Commissioners of the Rio Surco, the team responsible for managing this historic resource, cleaned them out and largely encased them in concrete.

The system of water flow from the Rio Surco as it is now used to reach all parts of Lima. Map courtesy of Javier Lizarzabruru Montani

One section remains visible as a flowing stream through parks past the Pentagonito in San Borja where Sunday cyclists meet up. The nearby Jockey racecourse is watered by this stream which can be followed from the Rimac through the back streets of Santa Anita, by the side of Colegio Roosevelt, crossing Javier Prado at the Trebol junction with the Panamericana close to Jockey. It flows down through Surco`s Jardim de Paseo del Bosque and circles Humboldt College, where it also waters the Club Germania, ripples past Colegio Hiram Bingham, and continues through the military air base to Chorillos and the sea.

Side canals water the parks above Javier Prado including the Huaca Santa Catalina in La Victoria, and the Huaca San Borja, the green areas of Avenidas San Borja Sur and Norte, and parts of Angamos, Thomas Marsano and Benavides.

In Central Lima, the Rio Huatica or Huadca took water past what is now the open air book market of Amazonas, into the Plaza de Armas, and provided a water supply for all the houses and streets of old Spanish Lima. It was built long before the Spanish. In colonial maps it is shown as a grid of channels taking water to every quarter of the then city of Lima.

There were several mills on the outskirts of the city here. Flora Tristan visited the city`s mint (Moneda) for stamping silver coins, which may have been located at what is now La Casa de Trece Monedas on the corner of Jiron Ancash and Abancay, a few blocks from the Plaza de Armas.

“The location of the mint seemed to be well organised. They have brought from London great blades, which are turned just like a wheel, by means of a waterfall.” The old building now houses the National Afro Peruvian Museum.

Side branches of the river went down into La Victoria, along what is now Renovacion. Mario Vargas Llosa describes his visits here in 1960s Lima to the prostitutes of the street which was then known as Jiron Huatica. Huatica is the name of the canal and the street, and like Surco it is the name of the Senor or Curaca, the chief of the territory, and the name of the land and water he controls. The tierra and the agua go together for the one is useless without the other, and pre-Hispanic Lima was managed by six chieftaincies each controlling an out-take, or bocatoma, from the Rimac, and the land it fertilised.

The water channel flowing past Huaca Huallamarca in Miraflores. photo courtesy Javier Lizarzabruru Montani

A branch from Rio Huatica passes along Grau close to the National Stadium, which was the site of a public swimming pool in the nineteenth century, and can be seen at the top of Salaverry where it enters Campo de Marte – one of the few areas of Lima where it is visible above ground – close to the Feria Artesenal where the fortune tellers, and curanderos will bless your future with incense, magnets, yellow flower petals and ringing bells. Anyone who plays sports or walks their dogs in the Campo de Marte will notice the complex of ditches and channels which border and cross all the green areas, and the culverts beneath the footpaths which allow the streams of water to reach every area of the park.

This stream is also diverted down Salaverry on a Saturday afternoon, watering the grass and trees of the central reservation along its entire length to end in the Parque La Pera del Amor. On a Saturday evening, waters tankers for San Isidro queue here to fill up with water from the underground reservoir of the park, now full of water, which is accessed under a green metal cover on the South side. These are the tankers which can be seen spraying the roadside edges and isolated trees, not with sewage as one Lima friend thought, but with Rimac water which has travelled many kilometres through ancestral canals to the edge of the sea.

Leaving the Rimac close to the Plaza de Armas, another canal took water to Magdalena via the five pyramids of Huaca Mateo Salado by the Plaza de la Bandera in Pueblo Libre. A field of roses irrigated by the canal until recently can still be seen among these Huacas.

The Rio Maranga took water to the many residences and temples of the Maranga people around what is now the Parque de Leyendas, the Lima Zoo, and so it was here with a good supply of water that the Universidad San Marcos was established in 1551. One of the great temple mounds here, for whose builders and worshippers their water supply had been created, was flattened to make room for the University`s football stadium.

The routes of the Rio Surco can be seen on Google Maps and the route of Rio Lati through Ate and La Molina is visible enough on Google Earth, as lines of greenery across an otherwise parched desert. Closer to the centre of the city the canals still flow but underground, out of sight. But if you look closely you can find and follow them.

There are some clues in the street names. The banks of the open rivers must have been pleasant places to stroll in the shade of the trees, and so alongside the Surco in Ate we have the Boulevard de Surco, and lower, the Paseo los Eucalyptos, the Paseo del Bosque and the Paseo de la Castellana.

In Rimac, the walkway of the waters, the Paseo los Aguas, was by a streamlet running behind the Plaza de Acho, and probably supplying water to the Convent de los Descalzos. Flora Tristan described it as a popular favourite walking place on Sundays. “The Paseo de Aguas…is beautiful but poorly located. The riverlet that borders it and the large trees that adorn it produce, in winter, a very unhealthy humidity. Women are almost all wearing skirts and many of them sit on the benches. In this position the dress reveals their knees.” Streets either side of the old Lima centre, close to the routes of the Rio Maranga and Rio Huachipa, are called Molino (the mill) of Montserrat, and Molino de San Pedro Nolasco.

The canals were raised above the surrounding lands, so that where they were built over, the roads, normally of a very predictable gradient, are seen to rise up as if over a bridge. This is evident in the back streets of Ate, and besides the Congress building on Jiron Junin. Part of Jiron Cailloma, two blocks North of the Plaza Major, was formerly known as Acequia Alta, the high waterway, and the road clearly rises to pass over a now buried stream.

Many parks are watered by sprinklers, but those linked to the network of Rimac water are crossed by channels and ditches, usually running round the sides with spurs towards trees and flowerbeds. You will see stone blocks, plastic sheets or wooden boards, which the gardeners use to direct the water, tucked under a hedge or in the cleft of a tree branch.

At the uphill end of the park, you should find the culvert where the water enters, and see the concrete covers in the roadway beyond. And at the bottom of the park – Lima has a gradient, from the Rimac to the sea, of something over one metre fall in height for every hundred metres – you should see an exiting culvert, and so you can follow from park to park.

Where the streams drained into the sea in past times, they may have worn away the loose soil and pebbles of Lima`s coastline, so it is likely that the Terrazas of Miraflores, the Bajada leading down from Barranco, and the Quebrada de Amendariz may have been the termination of rivers and streams. The Rio Magdalena reaches the sea close to the entrance to La Mistura. One branch of the Huatica, that passes down Salaverry, would have found its exit close to the Museum de la Memoria, where the road goes down to the beach. And in fact down on the coast road you can see its final achievement, a trickling of water now, but still watering the grasses and creating a generous fan of greenery spreading onto the beach.

Part of the Rio Huatica finally ends its 8km journey entering the sea below Miraflores