Having found the gnomon, thanks to Amy, I am determined to find out more about what seasonal festivals or rituals might have been carried out there. There are several sources that can help me, including accounts by the early Spanish, and of course the Huarochiri Manuscript.

The chroniclers tell us in considerable detail about Inca seasonal rituals. Better still, there are several independent sources that give us a more rounded view. The Inca king in Cusco celebrated “four solemn feasts”, according to Garcilaso Inca de la Vega, the most important of which was the Sun Festival, or Inti Raymi, around June 21, at the time of the Summer Solstice (as Garcilaso writes, in Spain, referring to the Southern Hemisphere Winter Solstice).

The second was a coming of age trial and celebration for Inca Royals, involving endurance tests and races. The third “was celebrated after seed time, when the corn had started sprouting.” Dances and sacrificial offerings were made to the Sun, “so that it would keep the frost from destroying the corn,” according to Garcilaso. The fourth was called Citua and was a purging of the city from diseases and other ills. It took place on the first day of the new moon following southern hemisphere spring equinox, a week or two after 23rd September.

Guaman Poma de Ayala paints a much more detailed picture, literally, with 398 drawings which include twelve showing the months of the year as farming seasons, and a further twelve showing them as Inca festivals or rituals.

His farmers celebrate April, the month of the moon, as the crops ripen. They harvest maize in May and potatoes in June, and put them into storage in July. From August to October they prepare the ground, sow the maize, and tend the young shoots. In November they irrigate the land and in November they fear that the rains will fail. In December they plant potatoes and quinoa, then weed their plots and protect them from foxes, deer and birds through January to March. Until the harvest, and so it begins again.

Some of Guaman Poma’s seasonal farming cycle is reflected in his calendar of rituals. In January the Inca “…offered sacrifice, fasted, made penance, and covered their bodies and heads with ashes… and went in procession to the temples of the Sun, the Moon, their gods and all the huacas.“

In February they made offerings of gold and silver. “This is the wet season, it often rains…they visit the huacas of the high mountains and the snows.”

In March black llamas are sacrificed, and red llamas in April. In June there is the Sun Festival, in July the harvest festival, and in August there is a ritual turning over of the soil by the Inca king prior to sowing.

In September, according to Guaman Poma, there is the ritual cleansing of the city described by Garcilaso Inca de la Vega, combined with the feast of the Moon, whilst in October the Inca pray for water with “hungry black sheep”. November, as today throughout Latin America, is the feast of the dead and in December there is a great Sun Festival, focused on the Summer Solstice.

Gary Urton found that there were three important seasonal events for the people of Misminay – harvest in April, planting in June, close to the reappearance of the Pleiades, and the coming of the rains in October. He linked these with Guaman Poma’s sacrificial rites of black llamas in March, red llamas in April, and black llamas again in October.

But to what extent are these relevant to events amongst the Mala stones, which are set in the warm coastal valleys, the Chaupiyunga, at 575 metres above sea level?

We have another source of information for the central coast. Pablo Joseph de Arriaga in the “Extirpation” talks of three festivals, and appears to be making a generalisation about all the places the Visitors attended, though much of his own experience was in the Chancay region, to the north of Lima.

“Confessions are made during the solemn festivals, of which there are three each year.”

“The most important of these is close to Corpus Christi, or even at the same time. It is called Oncoy Mitta, which is when the constellation Oncoy appears. They do homage to this constellation to keep their corn from drying up.”

Corpus Christi is a moveable feast, dependent on the phases of the moon, which could be a date ten days either side of June 10. The date of the reappearance of the Pleiades is relatively fixed.

“The other important festival” continues Arriaga, “is at the beginning of the rainy season, at Christmas or shortly afterward. This festival is addressed towards the thunder and lightning, to ask for rain.”

“The third is when they harvest the corn, which they call Ayrihuamita, because they do the dance of Ayrihua at that time.”

The traditional maize harvest in Cusco is in April, according to Guaman Poma, who in his Inca calendar calls the month Ayrihuay Quilla or harvest moon. Arriaga’s three festivals largely match with the April harvest, June planting and October first rains of Urton and Guaman Poma.

**********************************************

In the Sierra today, the most important indigenous festival for the Cusco region is Qoyllur Rit’i. People from the surrounding regions make an annual pilgrimage, with troupes of dancers and musicians, to the snowy mountain top of Ausangate. The pilgrims come from the farming lands to the northwest of the shrine, and from the pastoral regions to the southeast. They start the trek on Trinity Sunday, which means they can complete the festival and return to their towns and villages for Corpus Christi Sunday, a week later. It also means that they will be walking under a full moon.

Events for Qoyllur Rit’i include processions of holy icons and dances in and around the shrine of the Lord of the Snow Star. This is a festival that binds people together. Farmers and pastoralists perform the same roles and wear the same costumes although they speak different languages, Quechua and Aymara. The ritual culminates in the observation of the rising of the Pleiades before dawn.

**************************************************************************

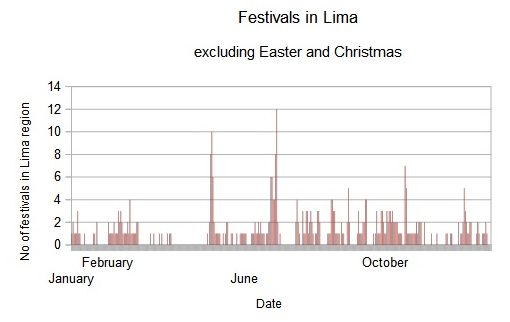

I am curious to see what are the dates of current festivals around Lima. I find a calendar of events for all the towns in the Lima region, and tabulate the data. There is a preponderance of festivals at the beginning of May called Fiesta del Cruces (the Crosses), the Cross of May, or the Most Holy Cross. Corpus Christi is widely celebrated, and will be on 20 June in 2019. In Lima, the entire month of October is dedicated to El Señor de los Milagros, The Lord of the Miracles. I plot the data. It is clear that today’s christianised festivals around Lima roughly conform to the pre-hispanic pattern of dates described by Arriaga: early May, mid June and October-November.

**********************************************************************

The historic festivals of Huarochiri and the stones were related to the seasons and so were fixed dates. On the other hand, Catholic feasts such as Easter and Corpus Christi are movable dates, two months apart, based on the Jewish calendar and dependent on the phases of the moon. In 2018, Corpus Christi fell on Thursday May 31st, and the following year, in 2019, it will take place on June 20th.

After the Spanish came, the people would carry out their rituals, or at least the drinking and dancing, at the catholic feast of Corpus Christi, as a form of camouflage. This causes some confusion. Nevertheless, with a close reading of the text it is possible to deduce the original dates.

The Huarochiri Manuscript talks of three festivals.

“They celebrated Paria Caca’s paschal festival on the first day of the period called Auquisna. Next, they likewise danced during Chaupi Ñamca’s time. Finally, in the month of November, …they’d perform another dance called Chanco.”

Paria Caca, the ancestor god of the people of Huarochiri, appointed one person in every village to lead the ceremonies. “Once every year you are to hold a pascal celebration re-enacting my life.”

He gave these people a title, huacasa or huacsa. “The huacsa will dance three times a year, bringing coca in enormous leather bags.”

The festival for Chaupi Ñamca was called the Chaycasna, meaning our mother, according to a marginal note in the original manuscript. This appears to be an Aymara or Jaqaru word. They dance the Hunatay Cocha, the Ayñu, and the Casa Yaco.

And in November, they dance the Chanco and the Ayñu. They perform the Chanco for Tutay Quiri, Paria Caca’s son.

The third and most important festival is for Paria Caca, called the Auquisna, for our father, we are told. Awkisa is father in the Aymara language. People race to Paria Caca, or other mountains, with their llamas, which they sacrifice.

It is clear that Chaupi Ñamca’s Festival was held in June.

“People schedule Chaupi Ñamca’s rites during the month of June, in such a way that they almost coincide with Corpus Christi. When the Yanca (ritual manager) has made calculations from his solar observatory, people say “they will take place in so many days.”

People used to drink for five days in the month of June, the Manuscript tells us, and “later, for fear of the Spaniards, they worshipped on Corpus eve.”

“The Mama people, in order to celebrate her festival on the eve of Corpus Christi, used to bathe Chaupi Ñamca in a little maize beer…laid out all sorts of offerings for her, and worshipped her with guinea pigs… “

“They used to stay there all night long, staying awake till dawn, drinking and getting drunk…they…danced that night drinking and getting drunk until dawn…After that they went out to the fields and simply did nothing at all, they just got drunk, drinking and boozing away and saying “it’s our mother’s festival!””

The next festival was in November, “just about coinciding with the festival of St Andres”, (St Andrew’s Day, November 20) when the Checa people would go on a a giant surround hunt, saying “we go in Tutay Quiri’s footsteps, we go in the path of his power.”

Tatay Quiri, the son of Paria Caca, was the community leader who extended the territories of the people of the manuscript down towards the lowlands. It may be the Tarayquiri whose mummified body Fabian de Ayala discovered in a cave in Santiago de Tumna, during the Extirpacion Visits. “Amongst the ancient captains and valiant soldiers . . . there was one called Tarayquiri . . . who died over six hundred years ago.”

This and others preserved ancestors were destroyed.

The Checa set out from Llacsa Tambo to “a place called Mayani, up above Tupi Cocha…they would trap some guanaco, brocket deer or other animals.” On the next day they would leave Mayani for Tumna. People would gather and wait for them at Huasac Tambo. “This Huasac Tambo is where a few rocks stand in the centre of the plaza of Tumna itself. In the old days, they say, people used to go there and worship on that spot.”

On the next day they spent the night in Pacota, and on the following day they returned to Llacsa Tambo.

The Tatay Quiri festival, like the October and November festivals described by Arriga, Urton and Guaman Poma, was focused on calling for the rains.

“On that occasion they used to ask for rain. People said, “now, in the Chanco season, the heavens will rain.”

“When they danced the Chanco, the sky would say “Now!” and the rain would pour down.”

The third festival in the Huarochiri year was Paria Caca’s Festival.

“They celebrate Pariacaca’s paschal festival on the first day of the period called Auquisna.”

We are told that people used to gather from far and wide to visit Paria Caca during his season.

“But, in the old times, they say that all these people used to go to Paria Caca mountain itself. All the Yunca people from Colli, Carhuayllo, Ruri Cancho, Latim, Huancho Huaylla, Pariacha, Yañac, Chichima, Mama, and all the other Yunca from that river valley; also the Saci Cayo, who together with the Pacha Camac come from another valley,and the Caringa and Chilca, and those people who live along the river that flows down from Huaro Cheri, namely the Caranco, and other Yunca groups who inhabit that river region, used to arrive at Mount Paria Caca itself, coming with their ticti, their coca, and other ritual gear.”

Whilst the writer describes the previous festivals as being for the Checa, and for the people of Mama, Paria Caca’s cult was more widely based. Its followers included the people, the Yunca, who had been conquered by Paria Caca.

“These Yunca groups, all the Yunca, … began to worship Pariacaca. To enumerate all the Yunca settlements in the whole area, would be very tiresome. So … we shall choose only a few of them … because all the Yunca shared one single way of life.”

After the Spanish, we are told, the people no longer went to Paria Caca to celebrate the festival, but to other mountains.

“Regarding all these places on mountains for worship of Pariacaca, it was only later on, when the Spanish had emerged, … that they were established.”

“Now they go to a mountain called Ynca Caya to worship from there. (The snowcap of Paria Caca is visible from this mountain).“

“(This mountain rises over the ruined buildings of purum Huasi and abuts onto another mountain called Huallquiri).”

“The Concha worship from that other mountain called Huaycho…Likewise the Suni Cancha workship…from that mountain called…“

“The residents of Santa Ana, those who live in San Juan, and all the ones called Chauca Ricma … worship from the mountain called Acu Sica, the one we descend on our way to the Apar Huayqui River. “

As the Spanish restricted their movements or sought to discover and destroy their sacred places, the people created their own new places of worship, closer to their homes or farmland.

The date for Auquisna is confused in the Huarochiri Manuscript, being identified not only with the great Pasch, presumably Easter, but also with Pentecost, fifty days after Easter, and with Corpus Christi, sixty days after Easter.

But the Manuscript states repeatedly and clearly that there are three Festivals, and the dating of Chaupi Ñumca’s festival in June, around Corpus Christi, is unambiguous. Pariacaca’s Festival then is the earlier date, “on the first day of the period called Auquisna.”

This all becomes clear if we see that the Auquisna is not a date but a season. It is the forty day period without the Pleiades, close to the fifty day period between Easter and Pentecost. It is represented by two dates, the start and the end of the period. Paria Caca’s festival is at the start of this season, but the season itself runs from late April to early June [1]. This explains why the writer of the manuscript writes, several times, that Auquisna season is at Corpus – the end of the period – and then crosses it out and writes Pasch, the commencement.

“Nowadays the Auquisna season <crossed out> [falls] comes in the month of June or close to it. It either occurs close to <crossed out> [Corpus Christi] the great pasch, or actually coincides with it. “

“Some people make this festival [Paria Caca’s] coincide with the great pasch, Easter. Others set it close to Pentecost <crossed out> [and Corpus].”

This would place the two festivals, for Paria Caca and Chaupi Ñumca, as the time of the disappearance and then re-appearance, respectively, of the Pleiades or Oncoy. The earlier festival at the end of April, for Paria Caca, is called the third festival, because the year ends here, only to begin again with the June rising of the Pleiades, the time for the highland celebration of Qoyllur Rit’i. April is the end of the year. Auquisna is a dead period. The new year begins 40 days later, or 37 in the Inca calendar, according to Zudeima.

In the world of Huarochiri, each of these festivals was associated with communal activities, offerings and sacrifices, and five days of drinking. Each also had one or several dances, and, perhaps, its particular music, in the same way as the Yanesha have three sacred song sets for different periods of the year.

The gnomon on Piedra 6 at Cochineros would cast a short but growing shadow, perhaps just touching the upper curve of the ellipse, in the first week in May. This would mark the disappearance of the Pleiades, the start of the Auquisna period, and the festival of Paria Caca.

Forty days later it would cast the longest shadow at the solstice on 21 June, probably reaching the lower curve of the ellipse engraved on the rock. Perhaps a week before then, the shadow would touch or even cross the line of dots, which could be used to measure its width. This would indicate the date of the festival of Chaupi Ñamca, the first new sighting of the Pleiades, and the start of the year.

[1] See Appendix for details of similar festivals for Pariacaca and Chaupinamoc in the Cordillera Negra hundreds of kilometres to the north.

***********************************************

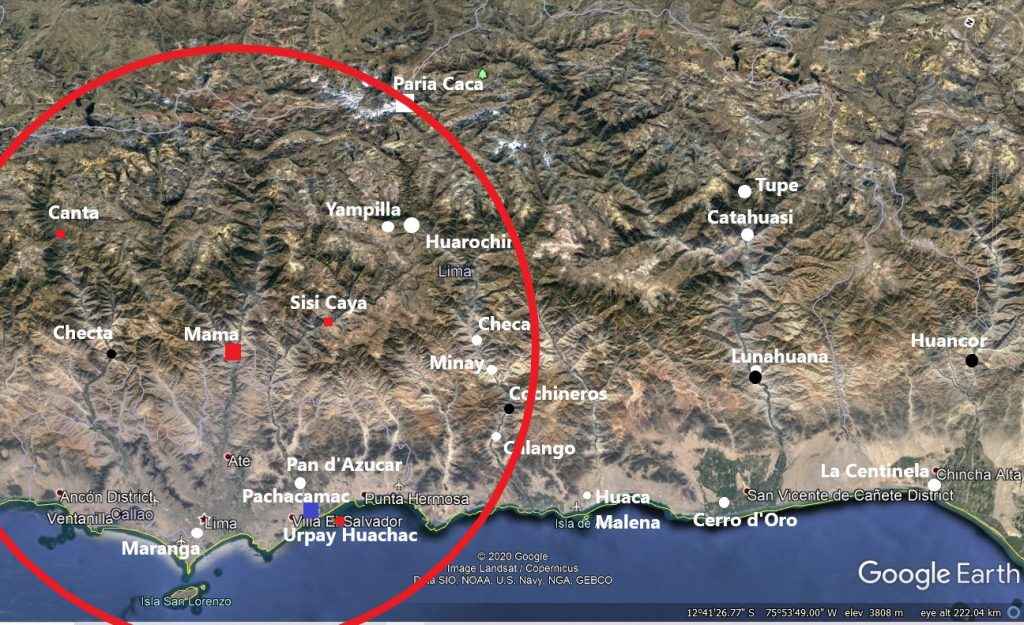

One of the important features of the festivals was that they brought people together. The Checa ceremonies of Chanco in November included, we are told, hunters from the lowlands, the Chauti and the Huanri, and people from Mama and Sisi Caya.

Chaupi Ñamca’s cult was based in Mama but she had four sisters. One was in Canta, fifty kilometres north, in the Chillon valley. Urpay Huachac was by the seashore or in the ocean, perhaps by the fresh water lagoon next to Pachacamac, forty kilometres south west. The third and fourth sisters stayed together in the Lurin valley, near Sisicaya.

Meanwhile Chaupi Ñamca’s brother Paria Caca was based in the mountain heights seventy kilometres east. So these huacas unified people across considerable distances. The Cochineros site sits within this range.

Above all, it was Paria Caca’s ceremonies that brought together disparate groups, from several river valleys, from the highlands down towards the coast. The writers list seventeen different peoples or ayllus who performed the rituals for Paria Caca in his season. And they emphasise that taking part in these communal festivals, incorporated you into the community.

“If a Huayllas man is married to a native Surco village woman and performs these rituals, the members of that community don’t take away his fields or anything else of his, even though he’s an outsider. On the contrary, they respect him and help him.”

**********************************************

Some time in June the Pleiades reappear in the night skies over the stones at Mala. After forty days absence, they will be seen to rise in the gap between the hillsides to a viewer at Cochineros looking upriver. The landscape itself provides a backdrop to measure the position. To get a better view, I would want to be higher up the valley side.

On my fifth visit to the stones, I look up at the hillside above the orchard for the first time. There appear to be horizontal lines of stones on the hillside. A quick clamber up and over the banked canal confirms that these are walls of un-mortared stones, arranged in lines. There is a long structure two metres wide but twenty metres long, paved with flat stones, with a neatly built straight wall at the back, made of a line of vertically positioned boulders. Another similar stone platform is positioned several metres higher up the hillside.

There are shards of ceramic here, simple undecorated brown ware, but no bones. Nor are there adobe blocks or mortar. These are not the ruined houses of Checas or Cotahuasi. They are long and narrow open paved spaces, finely made with fitted stones. They could be areas for drying crops. They could also be viewing platforms, looking down on the stones, and looking upriver towards the northern sky.

[1] See Appendix for details of similar festivals for Pariacaca and Chaupinamoc in the Cordillera Negra hundreds of kilometres to the north.