The Museo de la Huaca Malena is on a quiet street, and locked. In an office next to it a woman is sleeping, her head laid on the desk.

“Ahem. Excuse me. Hrrmm.”

She stirs and looks up.

“Can we visit the museum?”

“You have to go to the municipalidad.”

She wafts her arm up the road before subsiding back onto the desk. One block away is an elegant square, with a large college facing several restaurants, and a church opposite the administration centre. Unlike the spare concrete blocks that usually house the district offices, this is an elegantly plastered frontage with two tall columns holding up a balcony, round arched windows and doorway, and the national flag flying from the roof.

The Plaza is a shady space with flamboyant trees, their trunks painted white, and narrow flowerbeds lining the diagonal pathways. A woman in an orange municipal jumpsuit is weeding the lawn, pulling out long strands of wild grasses.

“This is so peaceful and green,” says Mayra,”it is just what I need.”

“This is why I like to get out of Lima.”

“This is why I had to come back from Caracas!”

Inside a large airy hallway leads to several small rooms. A receptionist in a wheelchair by the doorway points me towards one of them.

I am expecting to be told frostily “we shut at three” but instead the lady smiles and invites us to sit down.

“So where are you from?”

Mayra says she has come from Venezuela. She gets an appraising glance and a sympathetic smile.

I tell her I am a teacher in Lima investigating the petroglyphs in Mala.

“We heard you have a great museum here, with Wari textiles recovered from the Huaca?”

“You speak very good Spanish!” she replies, to my astonishment.

Silvia not only looks after the key, she is the guide. We walk across the square beneath the flamboyants and I ask if they have many visitors.

“Oh yes! Well, not so many. The people from Lima come to Bujama Alta, they go to the beach. There is no interest in our cultural heritage.”

“I think it is amazing, so many great cultures, incredible art, you are very rich.”

“You want to see our culture, but the Peruvians, they are not interested, only very few.”

Silvia unlocks the door to a single long room lined with glass cases.

The small room is packed with fabrics from the Huaca Malena, an artificial mound in the coastal plain with an area a little smaller than the Huaca Puccllana in Miraflores.

The site was a living area and administration centre in the early years of the Current Era, 200 to 55o CE, and then from 700 to 1100 CE it became, like the Huaca Puccllana, a burial site for Wari people, Silvia explains.

The Wari appear to have had their heartlands close to Ayacucho, in the now deserted city of Huari, at an altitude of 2800 metres. The city may have housed 70,000 people at its peak. But archaeologists have discovered signs of their influence at sites from the highlands to the coast, and from Cajamarca in the north to Cuzco in the south, across four hundred years. Their influence is seen in roads, buildings, ceramics, textiles and funerary customs across much of Peru.

Julio Tello was one of the first archaeologists to investigate this platform mound on the coastal plain close to Mala and he excavated over three hundred mummy bundles – mummified corpses typically wrapped in many layers of fine woven fabrics. The textiles were extraordinarily well preserved in the dry desert sands, whilst by contrast those in highlands rarely survive. That makes the Huaca Malena a valuable source of Wari textiles.

The site was still largely intact in the early 1980s, but over the next fifteen years half the site was looted and the top terrace of the huaca destroyed.

“The huaca is in very poor condition,” Sylvia tells us. “It has been sacked by huaqueros (huaca-hackers, tomb-raiders). It is surrounded by fields, people growing their crops.”

Like most guides I have met in Peru, Silvia seems passionate about her work and explaining it to visitors, and saddened that her appreciation for the treasures of Peru is not shared by all, or, indeed, by many.

“We have no resources. We can not protect these places or investigate them.”

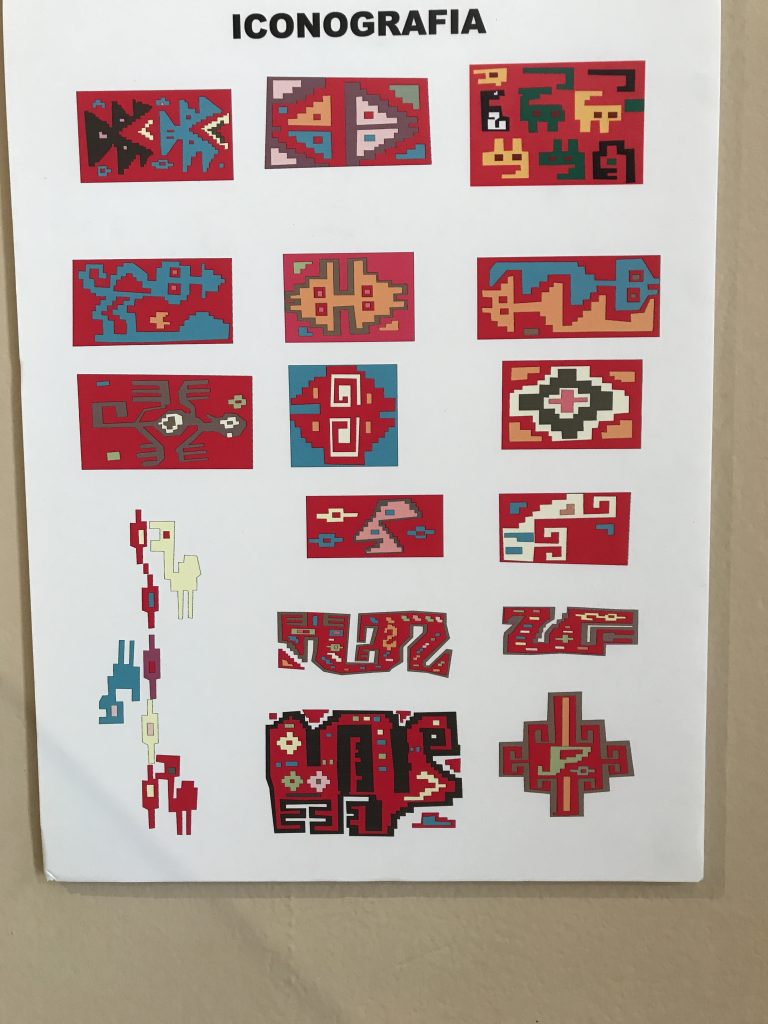

Since the Municipality took an interest in 1996 over four thousand textiles have been recovered, many of them discarded fragments left on the surface. The textiles have signs of local influence as well as Wari iconography. It may be more precise to say that these burials have textiles with Wari influence. The people themselves could be Malenos wrapped in Wari style cloths.

It appears that the bodies were buried with all the clothing they used in their life, typically long camelid robes for women, and shirts and loincloths for men. In addition to this functional wear there is a remarkable variety of headgear – caps, turbans, headdresses, hats, helmets, wigs and headbands, worked in cotton, alpaca, llama and vicuña, feathers, vegetable fibre and human hair. The women typically wear woven headbands, whilst the men have a greater variety of headdresses from plumes of feathers to wickerwork crowns. The variety of textiles is outstanding – thirty-two different weaving styles are used.

“Can we go and see the huaca?” asks Mayra.

“It is not open now,” says Silvia. ” It is not in a good state. It is far.”

As we leave I offer her a donation. “Oh no it is free!” she says with pride.

“I would be happy to pay if I knew the money would be spent to preserve and protect Peru’s heritage. “

“If you like you can adopt a textile,” she says.

“And what would that cost. A thousand dollars?”

“Oh no. It is just to pay the archaeologist to repair and preserve a piece of fabric. We have many cloths in storage but no money to care for them properly. You can choose the textile you adopt. And we will display it with your name next to it. Maybe five hundred soles.”

Silvia has been a joy to meet. I imagine she is poorly paid and unappreciated, but she loves her job and cares about Peruvian culture. I resolve to return and adopt a textile. What an experience it will be, too, to examine the textiles they have in storage.

************************************************************

“Lets go look at the huaca” says Mayra as we walk out into the Plaza.

We walk two blocks and we have reached the edge of town, with dusty lanes leading into the fields.

A low mound rises ahead of us, with a faded sign, and footpaths whose edges are marked with lines of stone. There are no fences or guides. As we walk along the paths we see deep pits whose sides are strewn with bones and torn soiled cloth, a few broken ceramics, and gourd vessels. The tomb-raiders have ravaged this landscape. We are looking at their discards. There are the traces of walls built with fist-sized cylindrical adobe blocks. Piles of mussel shells protrude through the surface. Skulls lie scattered over the ground, some arranged in tidy groups or grinning lines.

“Is this cranial deformation?” I ask Mayra, pointing to one of the skulls.

The skull protrudes strangely backwards, longer than it is high, unlike the two friends with which it rests.

“A lot of cultures did that, Nazca and Paracas, most famously. There are some good examples in the museum at Paracas. There are even, curiously, 78 cranially deformed skulls from Chanchay which now reside in a laboratory in Cambridge. But it was done by the Inca, the Huari, the Huanca. They pressed the baby’s head with a board or wrapped it tightly in bandages while it was still soft and growing, the first six months.”

“And what was the point?”

“Probably status and belonging to the group. One idea is that they wanted to have heads shaped like mountains. There was a tribe of North American Indians who were called the Flathead Indians, because they didn’t shape their skulls, unlike the tribes around them!”

“I suppose its another of those ancient practices that we will never be able to understand.”

“On the contrary. They were doing this body art quite recently on the eastern side of the Andes, perhaps they still do. I saw an old couple with elongated skulls walking through the riverside market in Pucallpa, just a few years ago.”

I find another skull with a neat little hole cut in it.

“We’ve got trepanning too!”

“And the bone has regrown. The patient survived. But can we stop looking at piles of skulls in a despoiled cemetery? It reminds me of Venezuela. Let’s have lunch.”

********************************************************************

Back in the plaza there is a restaurant called “La Chita Erotica”. I have no idea what that means.

In front is a stall selling melons, giant green striped melons, bright orange melons, pale white, brown and pimpled melons. Three boys are offering mounds of crushed ice raspadillas smothered with thick red and orange sugary fruit extract.

Inside a man and a daughter are eating, I asked if they have any Chita Erotica. They turn to each other confused. “What did he say? What language is that? No idea.”

The man rises and asks us slowly “How can we help you? What do you require?”

“Do you have food?” I mime eating.

“Ah si si. Siéntate” – have a seat.

” So you don’t hear my Spanish?” I say to the woman.

“Ah si, si, no. Ees Spanish? You are Spanish?”

“You could help me with a little Spanish, from time to time” I tell Mayra.

“You are doing fine. But maybe I should order the food.”

Chita, it turns out, is a fish, a local delicacy. Simply served, fried whole with rice and chips and a sweet onion garnish.

“Chita Erotica. Plump, and firm fleshed, I’d say.”

“Tender and succulent,” Mayra agrees.

“Presented to me naked but for a twist of lemon.”

“With a flat head and a bony tail. Don’t get carried away.”

********************************************************************

We resolve to explore higher up the valley beyond Cochineros the next day. Amerigo’s map had marked petroglyphs here, close to the modern villages of Minay and Checas. I had heard there was also an abandoned village here, Checas Alto, in a defensive position on a steep sided plateau with protective walls, as well as the less well preserved remains of a lower settlement, Checas Bajo, on the edge of the present town.

The bus upriver left from beside the marketplace.

“We leave at nine,” the driver says, “you have time to get a cafecito.”

A little coffee. Cafe becoming cafecito, the diminutive extension, is a particularly Peruvian style. A cup, tasa, becomes tasita. The origin is not Spanish or Castellano but indigenous. Quechua modifies its nouns and vowels by extensions. Hermanito, little brother!

“You should bring some food – there is nothing up there,” says the woman in the next seat. “But if you ask someone to prepare something they will.”

We find a breakfast bar in the market. A wooden shack open on two sides with

bread rolls, francesitas, little frenchies, stuffed with cheese, fried egg, sweet potato or chips. The walls are painted pink, with shelves of fruit for juices – pineapple, papaya in rows, a box of carrots, sacks of oranges, hanging bunches of bananas. There are herbs and ginger, parsley, white radish, a calendar of the virgin of Guadalupe on the wall and a bundle of the fleshy aloe vera cactus hanging upside down above the doorway, for luck.

Two people work in the tiny space. The mother is frying tortillas of egg and potato on a simple two ring gas stove, the daughter feeding fruit into a hand press.

“What do you want to drink, maca, quinoa…”

They have prepared infusions of grains and roots, cloudy soups. Maca, a small round tuber grown in the highlands, is often sold as a powder. In root form it can be white, grey, yellow or red. It is grown in the high cold regions above Lima, and has become highly valued as a “miracle” health food in China and Asia. Export of the living plant itself from Peru is forbidden. Chinese traders buy the roots in the highlands and transport them through Bolivia to establish their own maca cultivation back home.

We sit on stools sharing a pan con huevo, fried egg in a roll, and a pan lomo soltado, a roll full of potato chips with a dash of gravy, and two tall glasses of freshly squeezed orange juice. Around us, the market is preparing for the day. A man passes by with crates of gloomy silver-black fish, another with ripe papaya. Fruit sellers are arranging their plums and mandarins into attractive displays, pressed cylinders of soft young cheeses are piled high on plastic trays, avocados sit side by side with figs and cherries.

Back on the bus, as it heads up the valley, we tell our companion that we have been investigating the engraved stones at Cochineros. Her name is Wilma Manta, and she has has a round red cheery face like a little apple with bright white teeth. She could pass for thirty or forty.

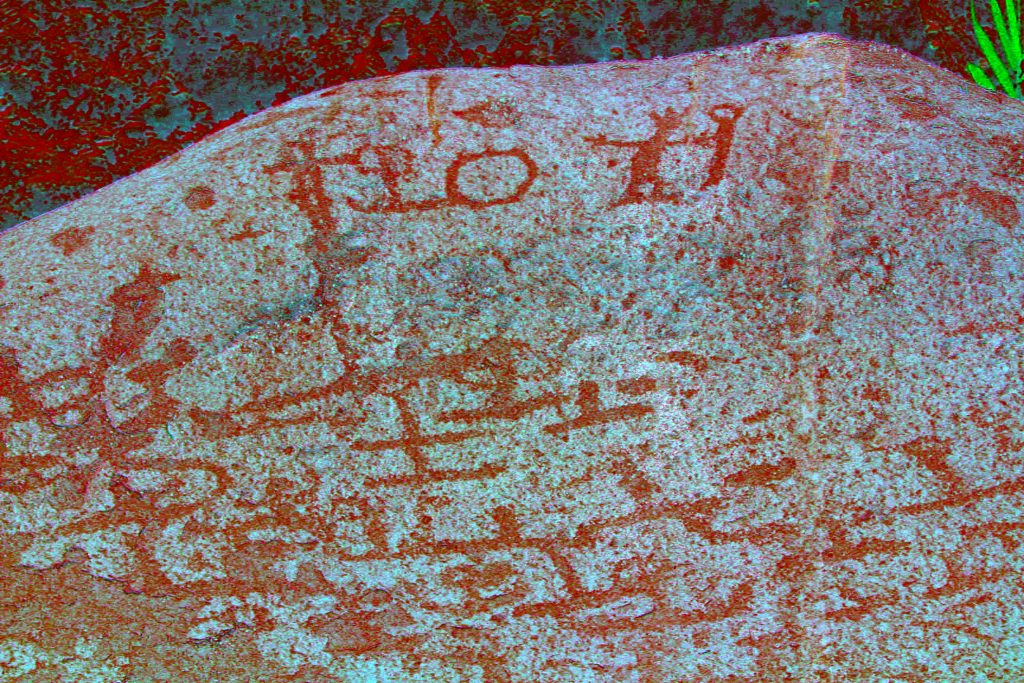

“Ah ya. There are some in Checas too. On my chacra among the apple trees. One grand one, another about so high. When I was little I found them and went running to my mother crying “mama why are there pictures on the rock?” And she told me they were there when she was little, and that was eighty years ago.”

So we decide to go all the way to Checas to see the stones.

Wilma has a house in Mala, and a house by the chacra, the farm. Her children stay in Mala to go to school. The older children study in Lima.

“My house is in the chacra, not in the village. My mother has a house in the village. “

Her children will work the land after her, she says. “They go to Lima to study but they will come back to work the chacra. Maybe they will get married and bring the wife back to Checas.”

Maybe.

“Actually I work at Regattas as a cleaner. It’s a new job just for the summer. Today is my rest day so I am going to my chacra.”

Regattas is a very expensive private club whose main site is on the sea front in Lima, where there are three private beaches, seven restaurants, a theatre, an Olympic size swimming pool, and more. The club also has a sailing centre in La Punta, the most exclusive area of Callao, with a clubhouse and private pier for sculling, eights and dinghy sailing. And there is the estate with a lake and woodland, near Chosica, an hour inland from Lima. Membership costs a six figure sum, in dollars, plus an annual retainer, and you have to be recommended by existing members. Club members, like the management board, are all men, though their wives, widows and daughters may use the facilities if signed in by a male member. Wilma is working at a fourth site, the Coastal club of San Antonio, which has two private beaches.

Everybody has a seat, though some are sitting on sacks of rice in the aisle. There are trays of eggs, buckets, bags suspended from the ceiling, wizened old women and wiry old men, a young couple with a small child, two schoolgirls, much laughter and joking. The village drunk sits on an upturned bucket between the seats.

The river today is a noisy rushing torrent. Passing Cochineros at 10.30 with a little cloud, the rocks stand out distinctly dark, blue-black.

The road past La Capilla is gravelled at best, and quickly becomes only one car wide. We pass a few motorbikes that stop by the roadside to let us pass. The familiar road speeds by, the bus shaking and groaning.

I am used to walking this road, but still find the blind bends on gravel with an unguarded drop to the river on one side uncomfortable. After Cochineros the valley gets narrower and steeper, and the road runs higher up the valley sides. For a long straight stretch the road runs on bare hillside with occasional open tombs above the road, little roofed cubicles of dry stone walling, at times just a small dark hole. The bridge at Minay takes us above angry brown waters and then rises up the hillside past rocky terraces of fruit trees to stop in front of a low building of adobe. The drunk gets out and stumbles away. He has no money to pay. The driver says nothing.

After Minay the journey becomes more precipitous. At times the road, only a little wider than the rattling, swaying bus, looks down fifty metres of steeply banked terraces to the foaming river below. Then again, there are parts where a scree of gravel and boulders plunges directly 100 metres into the waters. Or a vertical cliff of rock falls two hundred metres. I look out for interesting stones whilst assuring myself that a dozen passengers in a bus driven over the edge of a cliff into a river in flood three hundred metres below would be no worse off than if they roll down terraces of apple trees to land, beached, suspended in the branches, above the brown waters, or slide down the scree, overturning, scattering squawking chickens through the broken windows.

As each corner brings another horrific panorama I become, if not blase, nor indifferent, perhaps resigned to the journey. Holding tightly to the seat in front will make no difference, but I do it all the same. My fellow passengers look out on the drop, laughing and chatting, pointing downwards with evident delight. No doubt they do this journey every week.

When I finally get down on level ground in San Juan de Checas, I say to Mayra “I feel, if not reborn, then at least rejuvenated, a little younger. I have been given another chance.”

“You seemed quiet,” she replies, “but I thought you were just enjoying the view.”

Wilma explains that we can not visit the stones on her chacra as the river is too high. We would have to swing across on a platform suspended from a wire cable, the oroya, and she needs her husband on the other side of the river to pull us across. Instead she tells an elderly gentleman sitting in front of us that we want to see the ruins. Then she alights on a bend in the road fragrant with mango trees and with a wave she disappears over the edge into an apparent abyss. As the bus moves on round the bend I see her descending a steep slope with her several bags to a cabin below.

Arturo has a house in the centre of the village where the bus drops us. He is perhaps seventy, and unlike most passengers he has travelled without bags and baskets to unload from the roof.

“The old village is up there,” he says, pointing at a steep hillside littered with reddish boulders across which the remains of a wall can be seen halfway up. ““I will take you up the road and show you the way.”

We walk up the gravel road beyond the village – truly just a collection of half a dozen buildings, the centre of a farming area where most houses are based on plots of land down by the river. As the road curves round the steep hillside there is a footpath that starts to climb amongst the stones.

“There were steps up when I was a boy. They are mostly gone now. But you can still see the path,” Arturo says.

“What’s up there?” I ask.

“On the top there are many houses, it was a big town. An archaeologist spent many weeks up here recording everything and taking photographs.”

The path to Checas Alto is steep and broken. It was clearly once a staircase of paved stone, climbing the hillside to a gateway in the surrounding walls. This was a protected site, unlike the settlements in the valley below. It has defensive walls facing west and north. The rocks scattered over the hillside are rough sided, with a reddish coating. There are a few petroglyphs close to the staircase and entrance, pecked through the red outer layer to a golden yellow beneath. They seem crude and abstract, quite different to the finer markings on the blue black rocks of the lower valley. We see a spiral, several circles, and a pair of tumis, brighter than the other motifs.

The plateau at the top of the staircase is the size of modern Calango. We see walls made of small stones held together with clay and earth mortar. There are many tombs, and an area with a quantity of burnt camelid bones. There are ceramics, whole and broken pots, carved gourds, human bones. There are round buildings and rectangular buildings, but there are no houses. These are all tombs. It appears to be a necropolis, a City of the Dead.

“You have brought me to a town of corpses, a wasteland, a field of death,” says Mayra. “My country is dying, I would like a little hope.”

“These are the ancestors who would have been remembered, honoured, and brought food and drink. This is a place of celebration.”

“I find that difficult to see…”

“The spanish catholic church insisted that the bodies of their ancestors, their parents and grandparents, were buried underground. And the local people were appalled. How could they feed and remember their buried family? The spanish took bodies from places such as this and buried them deep. They even, during the hundred years of the extirpations, made a public bonfire of the venerated corpses of these people’s ancestors.”

“I know. But just a few weeks ago I was watching people die, on the street in Caracas. every day. Enough death. Let us see life. Birds, flowers, flowing water.”

*****************************************

We walk back down through the village. A canal of water runs along the hillside above the farmland and channels run gurgling down past fruit trees and under the road. There are apple trees here on the terraces but also scattered banana plants, avocado trees, mango, molle, chirimoya and guanabana, tumbo, pacay and lucuma. A pair of hawks circle on the valley winds above.

A simple casita, a little house, of white marble, sits in a patch of grass by the edge of the road. It is marked with images of apples and an engraved message.

“Although I have had to leave the ones I love, to travel the silent road, do not suffer or talk of me sadly, but laugh and chat as if I was still with you … you will always live in our memory – Joel.”

Fresh flowers and bottles of water have been placed on the grave. Mayra smiles.

“I can understand why Wilma travels two hours on her day off, to visit her chacra, where her mother showed her the stones forty years ago, and to where one day her sons will bring back their wives.”

26*****************************************

“I came back to Peru to study ten years ago,” Mayra tells me as we walk back down the valley. “My family left a Peru in crisis. The government had decided to delay the repayment of its foreign debts. Jubilation on the streets. Proud Peru stands firm. They will be begging us for a deal. We hold all the cards. Populist stupidity. The banks cut off funds and within a few years there is 10,000% inflation. I go to buy bread and it costs more than the day before.”

“This was the first Alan Garcia government.”

“That’s right. Then he decided to nationalise the banks and insurance companies. There were two armed terrorist movements operating in the country, plus paramilitary death squads probably taking orders from the president. So we went to Venezuela.

“In the 1950’s, after they discovered oil, the country had been one of the wealthiest nations, not just in Latin America but in the world,” she continues. “But they did little useful with the money.

“Still, when we arrived, there was a stable economy, steady oil revenue, modest inflation. We could make a living. My father took whatever jobs he could find – driving, unloading trucks, painting and decorating. He developed a good reputation with people from the prosperous middle class and after a few years he was running an agency supplying gardeners, cleaners, handymen, plumbers. He could always find people, many of them displaced Peruvians too, and he demanded high standards.

“I had a good childhood there. At first we were in a barrio, but later we moved to the outskirts of Caracas, in El Hatillo, and I walked to school. There were beautiful blue and yellow macaws sitting on the telephone wires. At the weekend I would go into the centre on the new Metro and walk through the Parque de Este, or meet friends at the Plaza Francia. My problem was homework, not hunger.

“When I left school Chavez had just been elected. There was an optimistic mood – his predecessor had been impeached on corruption charges. By the time I finished my archaeology degree at the Central University things were not so positive. The country had been awash with money in 1980, but the oil price was now half what it had been before we arrived. The government kept on spending. I got a job as a research assistant, working in Taima-Taima, and was happy there for several years. I was quite ignorant of what was going on in the country, and did not have any plans for the future.

“There were a lot of threats to nationalise foreign companies, and some were carried out. Oil companies, telecoms, power. It was a populist, nationalist policy. People supported it. But my father had seen it all before, eighteen years earlier. So he suggested I go to study in Peru. I was lucky enough to get one of the few scholarships at La Catholica.

“And how is Venezuela now?”

“People are thin. The monthly salary can buy two bags of flour, or four rolls of toilet paper. Money is worthless.”

“How?” I ask.

“My mother earns nearly a million Bolivars a month. That a little over the minimum wage. And it is worth less than five dollars.

“So how do people eat?”

“Often they don’t. My family is eating one meal a day. Vegetable soup. They are thin. They are just hanging on. And yet my parents refuse to leave. I could pay for their flights tomorrow. They let me take Amy, that was the best I could do for now.

“I think the stress, the uncertainty, the insecurity, years of it now, has made them unable to act, to make decisions. Like wounded animals, stubbornly waiting.

“I hear a quarter of the young professionals have now left. A million Venezuelans in Colombia. Half a million in Peru. It is the money they send home that keeps people alive. But the infrastructure is collapsing. My family keeps water in plastic containers. It is delivered to their district by trucks once a week. But sometimes the trucks do not come.

“They are lucky that no-one is ill. So far. Because it is impossible to buy basic medicines.”

We reach Minay, and there is a giant boulder in the centre of the town, decorated with diving sea birds – similar to those that we had seen sculpted in adobe at Maranga in Lima, by the zoo, as well as painted in red and yellow on the walls of the Old Temple at Pachacamac. I spend some time walking around it and taking photographs. It is good to have a diversion, as Mayra has fallen silent again.

We can see the remains of an old town too, ruins on the hillside above the road. We follow the road as it winds down the rocky hillside to cross over the river, and here we can see a pointed grey boulder four metres high, on the edge of the fields, close to the water. Marked on its peak are a dozen tumi forms and a roughly sketched human figure, holding a staff.

Walking down the narrow valley we see irrigated fields below a canal. There is an older, higher canal, now dry, crossing the hillside above collapsing andennes. There is a road visible in places, leading to a ruined town built on the delta of a quebrada, a dry side valley, rocky ground not suitable for agriculture, but flat with plentiful building stone. There are tombs too, besides the road on our side of the river.

“I have enjoyed our walks,” says Mayra, “and I would love to learn more about these enigmatic engravings. But it is more difficult for me now. I have my sister to look after.”

“I was wondering about that. What is she going to do?”

“She can get a job – in fact I have already found her work in a coffee shop. It is not well paid but it will keep her occupied. But I have to cook and be around for her.”

“I did a lot of investigations whilst you were away. Now I just need to put my ideas together.”

“You should write it up. Send me the chapters as you finish them!”

“Do you think so? But I don’t have any conclusions yet.”

“It’s a great story. And the best tales are those with an unexpected twist. Don’t worry about the ending. The ending will find itself.”

We have been walking two hours before we hear the sound of the bus approaching, and climb on board.

***********************************************************************

El Fronton and Lurigancho

Some 135 prisoners were killed in June 1986 by the Peruvian Army and Navy in retaking the El Fronton prison on an island off the coast of Lima.

On the same day, 124 prisoners were killed at Lurigancho Prison in Lima, 90 of them executed by being shot in the neck, according to a later government report.

Prisoners had taken control of the both prisons. Three members of the Armed Forces and a hostage also died.

The case was archived and 111 Marines absolved of responsibility by a military court between 1987 and 1989. In 2000 the InterAmerican Court of Human Rights ordered the State to investigate the case and bring to justice those responsible.

A judicial investigation was opened against eleven marines in 2005 and a further 22 in 2009. The case was finally brought against the 33 marines in 2012. More than 80 witnesses were interviewed including 35 survivors of the massacre and 8 Navy witnesses.

Retired Vice Admiral Jorge Montaya says the judicial process is the culmination of 30 years of bullying against the Navy military who just “did what they had to do”.

“The dead died in combat” he adds, “they were not assassinated”, pointing out that four marines died also.

The trial of 34 ex members of the Naval Infantry and Special Forces for the extrajudicial executions of more than a hundred and thirty-three prisoners in El Fronton opens in September 2017. The fiscal asks for penalties of 25 to 27 years in jail for the former marines. The trial is ongoing.