Mayra meets me in the Haiti Café on the corner of Parque Kennedy, where white haired men in grey suits sit at the pavement tables reading Gestion and taking an espresso with their crisp pork and sweet onion rolls. We catch a combi along Pardo, standing in the aisle, holding onto the roof bars, catching a view of the lighthouse as we sway round the Plaza Pardo. The conductor shouts “subi subi subi subi!!!!” as more people squeeze on, and then she yells at the rest of the bus to move down and make space. The passengers, already chin to sweaty shoulder, shuffle a few silent centimetres, passively resisting. Racing along Avenida La Marina we alight – “baja baja baja baja!!!” – two blocks west of the Parque de las Leyendas.

“Before we go haring off in search of secrets,” Mayra explains, as we walk through a park away from the main road, “I want to give you a basic grounding in the different cultures of the Peruvian Central Coast. What they built, U-shaped temples, giant platform mounds, roads, walls and canals, can still be seen in the city of Lima. There is a group of twelve, four thousand year old pyramids, just twenty minutes away from the airport.”

Walking towards the zoo we see a giant square mound of adobe towering over the zoo walls.

“Until the 1940s this was rural farmland on the outskirts of Lima,” explains Mayra, “but there were dozens of mounds rising above the plain. Three different peoples built here, over at least a thousand years.”

The earliest platform mounds, truncated pyramids, were built by the Lima people, using small hand made bricks of mud and clay. After five hundred years of occupation, the site was mysteriously abandoned, about twelve hundred years ago. Two hundred years later, the Ychsma people built their own ceremonial mounds, plazas and storerooms closer to the sea. They sited some dwellings on top of Lima mounds, and buried their dead there. Besides the temples and palaces there was a town of residences and workshops, a walled settlement with streets and canals.

“When the Incas came to the coast, in 1476,” Mayra continues, “they tidied up and re-organised, adding new buildings, extending or building on top of Ychsma mounds.”

We head past the car park, where a line of kiosks sells toy gorillas, bright plastic binoculars, bags of peanuts, and parasols, to queue at the entrance. Once inside, past the cafes and the gift shops, we find ourselves facing a low mound with internal walls of large square blocks of adobe. The signboard tells us that the Huaca San Miguel was a storeroom for maize, beans, dried meat and fruits, in the later years of the Ychsma.

Bearing to the right we reach an enclosure of alpacas behind which rise the steep sides of a rectangular mound, with vultures peering from the top.

“This is Huaca Tres Palos,” explains Mayra. “We saw the front of it above the zoo walls when walking up here. It is 150 metres wide and 170 metres long.”

“And it looks about twenty metres high. If it is all made of those adobe bricks, it would need about five hundred million of them!”

“There’s a theory that it was a shared labour under central direction – each family or family group was asked to contribute a hundred bricks a year, say, for ten or a hundred years.”

“It would be a hundred bricks a month, from 5000 families, for a hundred years,” I say.

“Which would make its a symbol of the community. Yet many archaeologists see Peruvian cultures as elites working together with powerful religious hierarchies…”

“In the same way that some archaeologists in the past saw racial divisions everywhere they dug…”

“Whereas Caral, the five thousand year old civilisation to the south of here, is being interpreted as a prosperous civilisation built on free trade across regions and cultures, with women of high status and without conflict.”

“Perhaps that is due to the Director of the investigation, the woman Ruth Solis Shady?”

“She certainly has a personal perspective.”

We reach the back of the Huaca. There is a break in the centre of the rear wall where a steep ramp leads up to the top.

“The Incas used Huaca Tres Palos as an inn or way station, a tambo, one of hundreds placed at regular distances throughout their empire to support Inca travellers. The Spanish built a private house on top. But the ramp is the original Ychsma entrance, and there are the remains of four Ychsma structures on top, including an astronomical observatory.”

“Really, with telescopes?”

“I was just saying that to intrigue you. Actually it was thought to be an array of 96 wooden posts, in two 6×8 grids, evenly spaced.”

“Like posts to hold up a roof.”

“Some people have interpreted it as a giant sundial.”

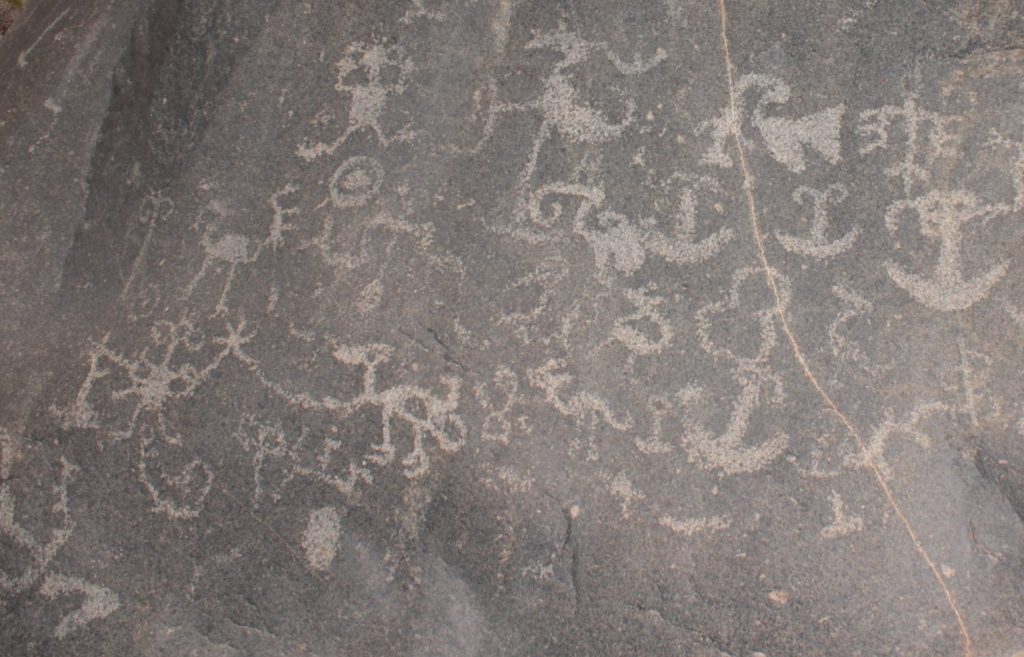

“You only need one post for a sundial. But it does remind me of those grids of dots marked on the stones at Mala – the 3×6 grid, the 7×5 grid, and a 3×4 grid, all marked on the same rock face.”

“Maybe they just enjoyed number theory, or pretty patterns.”

We leave the Huaca, walking along a wide grassed area where families sit sharing lunch from styrofoam containers. Besides the lawn is another long low mound with great trapezoidal ribs of smoothed adobe poking through the surface, and fragments of bone and seashells shine whitely on the surface of the mound. At the far end is a cactus garden beside the Museo Eppendorf, and beyond rise more great mounds.

“Those two are five hundred years older, from the Lima culture,” says Mayra. “They are made of thin, flat bricks, rather than the squarer blocks of the Ychsma. The adobitos are arranged in a series of horizontal rows like a books on a shelf, one shelf above another. Its called librero construction.”

Huaca Middendorf, to the front, is a dark mass with steep sides and a tiny watchman’s hut perched on top. Behind stands Huaca San Marcos, across a busy arterial road. At thirty metres high, three hundred metres long and one hundred and twenty metres wide, it is an imposing presence. Its slopes slump gently, unrestored and little investigated.

Walking towards these mounds we cross waste land at the back of the park. Mayra points out a raised canal, now dry, heading towards another low mound.

“All this was a city, with its offices, churches, houses, workshops, cemeteries, and plazas. And it had its own water supply, a seven kilometre long canal from behind the Plaza de Armas to bring water from the river Rimac.”

Following the canal back towards the zoo we reach a great wall of smoothed adobe, three metres high in places, which runs somewhat to the south of east and then turns ninety degrees and runs down the side of what is now the zoo.

“We are outside the walled city of Maranga,” says Mayra, “though it now contains the Jardin Botanico and the Laguna Recreativa, where we can hire a boat in the form of a giant white swan and pedal through the Tunnel of Love.”

“Lets do it!”

“I was joking. Though the Tunnel, bizarrely, does contain a 3D scale model of Machu Picchu.”

We follow the much restored wall for three hundred metres to reach a swinging bridge above a lawn where grey deer delicately graze. The bridge takes us over the adobe wall.

“Here you are. The original city of Lima, built by the Lima people, extended by the Ychmsa and added to by the Inca. The walls enclose an area half a kilometre wide and eight hundred metres long.”

We pass the sea lions and the penguins on the left and head toward a large flat topped mound.

“The rest of the city lies behind this, small low buildings, still being excavated. The Ychsma built ten platform mounds outside the walls, but just this one inside the city. It has a very interesting frieze, moulded in clay, of diving sea birds.”

“And we saw diving sea birds drawn on the Mala rocks!”

“They are also shown in an adobe frieze at La Centinella, another giant pyramid complex on the coastal plain, and at Pachacamac. That is how it is. Imagery gets recycled, time and again. And on the coast, for fishermen, diving sea birds are an important indicator to locate the schools of fish, a sign of plenty.”

“So let’s see if I understand this correctly,” I ask Mayra. “The river delta of the Rimac, and several neighbouring valleys, were occupied by the Lima people 1700 years ago. They built enormous rectangular mounds hundreds of metres long using small flat adobe bricks, adobitos, arranged like shelves of books. They were here for five hundred years. A few hundred years after they left, the Ychsma people came, not just to Lima but to neighbouring valleys. They built giant ramped pyramids made of large rectangular bricks, and they also built their houses and buried their dead on top of the Lima mounds. And then after five hundred years, the Inca came, formed alliances with the Ychsma, collected tribute in the form of food and cloth, and added smaller buildings to Maranga.”

Mayra smiled.

“Can you see now why I wanted to show you this before you start interpreting the drawings on the stones as this or that people come and draw llamas, and then some other group draw birds? Some people like to categorise and draw boundaries, particularly if they come from a culture that defines itself by boundaries. They see hierarchies, conflicts and religious elites, if those are the touchstones of their world. But sometimes the bigger picture is the continuity and the linkages. I believe the stones can teach us about that.”

******************************************************************

We stop to watch the hippopotami wallowing in a concrete pool, in front of the 1500 year old Huaca 32.

“So have you been able to date the tumis?” Mayra asks, wiping some lucuma ice cream off her nose.

“ I have an answer, but it is neither a yes nor a no.”

“Explicame, por favor!”

“I wanted to categorise the drawings on one panel by brightness, and relate that to age. But there are no tumis on that panel. There is one white mark above the heart, that could be a tumi, but it is not well drawn. It appears to be recent.”

How recent. 1750, the date of the Huarochiri rebellion?”

“It could be, plus or minus one hundred years. There is a clearer tumi to the left of the main panel, with a double ring handle. And on the opposite face of that rock there is a large handled tumi. Based on brightness, all three of them appear to be older than the heart, but more recent than the dot track.”

“You mean they were made sometime between the Spanish invasion and the present? Then it is the rebellion!”

“It’s not that simple. On the north-facing panel I have only one calibration point, JMJR’s initials. There is one large, bright tumi, but there are many poorly drawn T-shapes, which are a good deal fainter. That rock face does not have a shiny black surface, and there is little variation in brightness.“

“What does that mean. Tell me simply.”

“On the main front panel, there is a wide range of image brightness, the drawings appear to be darkening with time. But to the side of that panel, and higher up, and on the opposite face, we don’t see that. Maybe even older images remain bright. I am saying that I can’t tell.”

“So that’s the end of my exciting image of the rebels crossing the river, calling on the gods to bless their knives before they march on Lima?”

“You can still believe that, but without a tumi on the main panel, there is no dating to support the theory, nor to undermine it. And there’s more.”

I pull out my phone and run through some of the photographs of the rocks.

“Here, we have seven tumis, with curved blades, all drawn together on one panel. The shape, the styles are similar. They are drawn smoothly, fluidly, but lightly, sketched on the surface of the stone.”

I pull up another image.

“Here, on another rock, we have these five thick, round-ended blades, and the shaft is much wider. These are fully drawn, worked deep into the rock.”

And I open up a third and fourth photograph on the screen.

“And these are the rough drawn T-shapes, twenty or thirty of them on another two panels of two more rocks.”

“So not all tumis are alike,” says Mayra.

“You have just shown me that two platform mounds, side by side, can be separated by five hundred years or more. To see the difference, we have to look at the adobitos. I am saying that these tumis too, can be differentiated by shape, by the manner in which they were drawn, by choice of rock panel and by brightness. Even without detailed analysis the tumis can be put into five groups; tumis apparently being held by humans would be a sixth category. Maybe the tumis too span different cultures and hundreds of years.”

We reach the sea lions’ enclosure, which stinks of fish. Several herons have descended onto the rocks to stand watch over the pool.

“An image is drawn onto these rocks eighty or a hundred times, and yes, the image is drawn in different styles and forms, but people are drawing the same object are they not? A tumi, a ceremonial sacrificial knife, surely? And this image repeated so many times is specific to this site. It is not a llama or a serpent, which we see at every petroglyph site from north to south. This must tell us something!”

“But the image could have been drawn by different people over a long period of time, maybe a few hundred years. I have another idea…”

********************************************************

“When we had our icecreams by the hippopotamuses, you summarised Lima history, and it was very good. But something was missing. The Wari.”

We are walking back past the kiosks selling packets of peanuts and salted maize kernels. Three generations of a family sit on the grass beneath palm trees. A young woman nurses a baby, and the husband with thick dark hair watches. Meanwhile the grandmother, dressed in woollen stockings, flat black shoes, and thick layered skirts, with two plaits of dark hair hanging down her back, talks and talks and talks.

“After the Lima people and before the Ychsma, there was another culture here. The Wari, a highland people from around Ayacucho, appeared – with their burials, their designs, their cloth – on the central and southern coast about 1300 years ago.”

Through the front gates, outside the park, past the lines of yellow taxis, we walk below the high facade of Huaca Tres Palos and turn to walk along its longer side, towards La Catolica University.

“There are no signs of the Wari here, at Maranga, but they buried their dead on top of another Lima platform mound and we can walk there in an hour or so through modern Lima.”

A stream of traffic flows by, buses sounding their bleak mournful horns in frustration like whales, and taxis, hoping for a fare, blaring at every pedestrian.

We walk on.

“If these knives or tumis on the rocks are a sign of conflict,” I ponder, “they could have been made many times. We have tales of highlanders taking over the lowlands, then the Inca coming to the central coast, and then the Spanish. Inca fighters marched on Lima from the highlands in 1536 to fight the Spanish, they could have come this way. And then there were rebellions against the Spanish – Taki Onqoy, the Huarochiri Uprising, Tupac Amaru. It may be that every time there was a conflict, people would visit the site and mark the stones with images of blades.”

Mayra nods.

“But I see some problems with that.”

On the other side of the busy dual carriageway are the grounds of Pontificia Universidad Catolica del Peru. More usually known simply as Catolica or PUCP, it was founded in 1917 as a Catholic institution to defend against the liberal ideas, and even atheism, that some feared were being promoted by the four hundred year old University of San Marcos.

“Firstly, their weapons were maces and slingshot. These knives were not for fighting, they were used in religious ceremonies, for sacrifice and for divination. When iron became available, these soft blunt copper tools became obsolete. So I have another proposal.”

“Go on.”

“These were metal objects. Rare, high value items to be left in burials or traded. As were the tupus that we see, as were the mace heads, the porras, without their shafts. These rock drawings look like advertisements for a guild of metalworkers.”

Mayra interrupts my thoughts. “One researcher suggested something similar, but he also wrote that “. . . metal was only known in the valley of Mala with the coming of the Incas in 1470”.”

“There is the Inca fallacy again. The Incas worked metal, so metal work is Inca. There are drawings on these stones of metal objects. So clearly these people who drew them had metals. To say that therefore the drawings must be Inca . . . it is a circular argument. Metal working in Peru is thousands of years old.”

“Quite right,” says Mayra. “The Chavin were using copper around 1000 years BCE. In fact the earliest worked metal was found in a coastal valley just outside Lima at Mina Perdida, dated to 3000 years ago.”

“Those copper foils were the oldest evidence of metal working when they were found,” I pointed out, “but ten years ago a necklace of gold beads was found in a burial near Lake Titicaca dated to four thousand years BP.”

“The oldest not just in Peru but in the Americas.”

“In fact, there are mines in the hills round Mala. They are visible on Google Earth. When we walked up the valley and found the tombs broken open by the new road, and the scallop shell necklace lying on the ground, that quebrada, that dry valley, leads to some mines, a few kilometres to the south. And there appears to be a well built trackway to reach them.”

“So people could have been working in mines, just two hours walk away from the Cochineros rock drawings?”

“If the tumi drawings were left by a militia marching on Lima, we should be able to follow the route by its rocks marked with tumis. Now I am thinking that we might see a trail of such marks leading up and down the valley, perhaps to a mine or a metal-working centre.”

“We should go back to the valley and do some more exploring. And maybe check out the freshwater shrimp at the riverside restaurant.”

“But we also have to visit Yauyos and talk to the women who wear the tupus…”

“And I have still to show you the Wari presence in Lima.”

“I know where I want to start. Calango.”

“Ok. But let’s finish the Lima tour first. You need to see the whole context.”

**************************************************

August 1994. The teenage Keiko Fujimori becomes First Lady of Peru after her parents’ divorce. At the age of 19, she is waving to crowds from an open topped car and attending dinners with heads of state, as her father’s consort.

April 1995. A judge reopens the investigation into the killing of fifteen people at a fried chicken party, a pollada, in Barrios Altos. General Hermoza and other military refuse to testify.

June 15 1995. Albert Fujimori signs an “amnesty law” that pardons all Army officers accused of human rights violations since 1982. The La Cantuta killers who had been convicted two years earlier are freed and the Barrios Altos investigation is halted.

September 1995. Alberto Fujimori launches a “sexual health” programme at the Beijing World Conference on Women which includes voluntary surgical contraception – sterilisation by tubal ligation. A law is passed allowing the surgery to be carried out in state clinics. Between 1996 and 2000, 260,000 women will be operated on. It appears that the initiative is supported financially and logistically by the US AID Programme. The health officials have targets of up to 50 operations per day and the numbers sterilised are compiled and reported directly to the president’s office. Those are documented facts. Allegations of operations without consent, of operations without anaesthetic, of kidnapping women and taking them to the operations centre or offering them gifts of food to tempt them into the clinic’s cars begin to surface in 1997.

Fujimori supporters in 2017 say the claims are defamation from their opponents, though the basic facts are published in a report from the Ministry of Health, whose compilation, like the Truth and Reconciliation Report, was intended to be a part of the national healing and moving on. I ask some of the supporters online about these issues, and one of the answers I receive is, “these people (the indigenous indians) are lice and fleas. Lice and fleas.” There speaks the authentic voice of the Conquistadors, in 2017.