There is a smell of fish and salt in the air in Chincha. It is only 5 kilometres from the sea, 100 kilometres down the coast from Mala, 55 kilometres beyond Cañete. There is a well known petroglyph site near here at Huancor, up a river valley 33 kilometres from the coast, just two days journey for a llama caravan. So I have headed south again to take a look at it.

Archaeological studies in the area show that the valley was inhabited before the coming of the Inca by the Chincha people. Chincha means jaguar, an animal of the Amazon forest. Fray Bernabé Cobo tells of a star or constellation representing the tiger, called Chuquichinchay. Chincha villages and cemeteries have been found not only by the coast but throughout the middle and upper valley too.

Broad swathes of the coast are thought to have been controlled during the Late Intermediate period, the five hundred years before the Inca influence reached them, by powerful, politically centralised groups. But rather than the widespread cultures of the Chavin and the Wari that came before, and the Inca that came after, these were local groups, limited to one or two river valleys. The Chincha kingdom would have flourished then, as would the Ychsma in Lima and Lurin, and the Chancay and the Chimu further north. Inland there were the Yauyos and the many peoples of Huarochiri. The Huarco in and around Cañete developed large settlements, and were organised enough to hold the Inca at bay for years. The picture in Mala and Chilca to the north is less clear.

When the Inca forces began to move up the coast, the Chincha gathered 30,000 fighting men, but the Tupac Inca offered peace. Subsequently the Incas resettled people from other regions in the valley, and Inca nobles from Cuzco spent part of the year there, whilst the Chincha chiefs in turn spent some of their time in Cuzco.

It seems the Incas never dominated the Chincha. Inca structures at Huaca La Centinela, the coastal ritual centre, stand beside much larger Chincha buildings.

Only a few generations separated an independent Chincha from the Spanish invasion and the founding of Lima in 1535, and the earliest Spanish writers. Pedro Cieza de León describes the realm of the Chinchas as a “great province, esteemed in ancient times . . .splendid and grand. . . so famous throughout Peru as to be feared by many natives”. Their wealth and power was said to have supported major Chincha incursions into the highlands while the Incas were still consolidating the Cusco region.

The Chinchas had an abundance of gold and silver and their land was highly productive with a population of 25,000 persons when the Spanish conquered it. “ I doubt there are now five thousand, so many have been the hardships they have suffered…the diminishment of the people of this great valley is because of the long civil wars that were fought and the taking of them to serve as bearers…very few of the native llamas remain because in the civil wars they finished off most of the many that were here.”

Pedro Pizarro, a cousin of the leader of the invading Spanish forces, Francisco, provides first hand observations of the Spanish encounters with the Inca beginning in the early sixteenth century. His Relación del Descubrimiento y Conquista de los Reinos del Perú (written nearly 30 years later in 1571) notes that the lord of the Chinchas was carried by litter in an honoured position in the Inca royal procession. According to Pedro Pizarro, the Inca Atahualpa played chess with his Spanish captors and chatted as they awaited the massive ransom of gold and silver that Inca subjects were bringing from across the country. He told them that the Chincha lord was a good friend, and master of 100,000 sea-going craft.

Francisco Pizarro claimed the lands of Chincha for himself, having heard of their productivity, and later passed them on to his brother Hermano.

Fray Cristóbal de Castro and Diego Ortega Morejón interviewed older inhabitants of Chincha in a document referred to in shorthand as the “Relación” (1558), describing diplomacy and political maneuvering between the intact Chincha leadership and Inca representatives. From these accounts comes a picture of Chincha as a centre of coastal economic power distinct from the north. It may have grown in power when the Incas subjugated the Chimu, another coastal trading power with a fleet of boats, about ten years before they turned their attentions to the south and central coast.

Part of the Chincha Kingdom’s political capital derived from access to a powerful and prestigious oracle called Chinchaycamac. ”Out of a rock came the voice of an oracle” according to Pedro Cieza. The Inca relationship with Chincha was more as allies than as subjects, as it would be at Pachacamac, and the local people continued to worship at Chinchaycamac as well as recognising the Inca sun god.

In 1970 a previously unknown Spanish document was found in a Madrid archive by Peruvian archaeologist Maria Rostworowski de Diez Canseco. The text has neither date nor author, but its title translates as “Notice (Aviso) about the rules under the Indian government during Inca times and how they shared the land and taxes” – commonly known now as the Aviso.

Maria Rostworowski proposed that it dated to the early 1570s and had been written by a Spanish clergyman stationed at the Dominican mission in Chincha. The “Aviso” describes the Chinchas as managers of a massive maritime trading operation stretching from Ecuador in the north to the south coast of Peru, trading copper from the southern Andes for Ecuadorian commodities — gold, timber, emeralds, and spondylus shell.

The Aviso presents a picture of a society or a kingdom which commanded the seafaring skills, boats, and trading networks that the Inca lacked, a coastal complement to their state controlled distribution network in the Sierra.

“With their sales and purchases they went to Cuzco and throughout the south, and others went to Quito and Puerto Viejo, from where they brought a great amount of Chaquiras of gold and beautiful emeralds and they sold them to the chiefs of Ica that were their good friends and closest neighbours. And so a lot of emeralds have been taken from the tombs of the dead chiefs of Ica.”

Chaquira means bead or jewel, as in the Colombian singer Shakira.

The evidence for the Chincha sea trade is limited. But rafts of balsa, grown in the tropical forests of Ecuador, were still being used off the coast of Peru into the nineteenth century.

The triple-mound complex of Centinela, Tambo de Mora, and La Cumbe was probably the seat of Chincha political power. The site stands five kilometres west of the centre of the present day town of Chincha Alta. There are three great mounds, north of the river and just two kilometres from the sea.

La Centinela is the dominant great pyramid. On the crumbling adobe walls at the top of the structure is a frieze moulded in high relief. It recalls similar moulding at Chan-Chan, the capital city of the Chimu, Peru’s other great coastal culture of the period. The crenellated diamond decorations include a spiral wave motif. Below is a sea bird, diving downward into the water.

Visible across the fields from La Centinela, closer to the river and the sea, there is a pair of pyramids on either side of a split level central plaza at Tambo de Mora. And 200 metres to the north is La Cumbe, a pyramid 200 metres by 150 metres aligned parallel to the coast. This is thought to be the centre of the oracle, the Chinchaycamac, which may have its origins in the Paracas culture from 900 BCE. The surrounding areas housed textile workers, ceramicists and silver workers.

The old roads are still visible radiating out from La Centinela, running in straight lines to the east and south across the coastal plain. They would have transported goods and people to the Paracas valley to the south and toward the highlands of the Andes a week’s journey away. One points straight up the river valley of San Juan to Huancor.

***************************************************************

I am told that the buses to Huancor go from a road by the side of the market “a la izquierda del esquinita”, on the left of the little corner, and it seems to be maddeningly imprecise and yet turns out to be entirely accurate. A man with a clip board is marshalling the vehicles, a variety of private cars operating under some form of co-operative framework: each car’s time of arrival and departure is recorded, and they follow the manager’s instructions. As new cars arrive they join the back of the queue, and when they reach the front they tell the clipboard man where they wish to go and he shouts out the destination for passengers. For someone from the fighting streets of Lima, this is a revelation, a miracle, a thousand year leap forward, an astounding breakthrough equivalent to man discovering fire.

I ask the clipboard man for Huancor, and he finds a taxi driver heading in that direction, who agrees to drop his other passengers and take me the rest of the way for an extra ten soles. Twenty minutes later I find myself in open countryside.

“Is this a village?”

“It is a caserito, of three or four houses.”

It looks like the dusty junction of two tracks.

It is in fact Huanco, only an ‘r’ away from Huancor, but 15 km in distance, on the opposite side of the river, and south rather than east. Rather than waste the journey I pay off the taxi and set out to walk back through the farmlands.

Broad flat fields spread out on either side, separated by bridleways and irrigation canals. The broadest canals are up to six feet wide, crossed by bridges made of half a dozen great trunks of wood.

Field by field, sluice gates (each one with a name painted on – Dona Esmerelda no 4) can be opened to let the water into deep but narrow channels running down the side or centre, from where lateral ditches take them to either side, and so to simple hoed furrows in the earth irrigating the lines of crops.

I had spent a weekend walking in this valley some months previously, in the Christmas holidays. Back then, most of the fields were dry. Barely one in ten had crops. “We are waiting for the rains to come. Waiting to plant the seeds. We should have been planting cotton weeks ago, but there is still no rain,” a farmer told me.

The rain does not fall on the coast, which is more or less perpetual desert, but on the mountain slopes of the Andes above, which drain into the rivers which water the valleys and finally spread out onto the coastal lowlands where most of Peru’s food is grown.

The northern river watering the lowlands, the Rio San Juan, had been just a trickle in the broad river bed, whereas the southern Rio Plata, was entirely dry. But now the rivers at Mala, Cañete and Chincha are muddy brown torrents.

It is pleasant to walk through these fields, with occasional labourers clearing out the ditches, tractors ploughing over the dry soil, and birds flying ahead along the bushes that line the canals. The broad flat fields present a very different prospect to the narrow strips by the river higher upstream, or the hillside terraces, andennes, where the villagers farm on steep slopes higher up the valley.

Hawks wheel overhead and small birds fly ahead of me from bush to bush, and then a troupe of 30 or 40 large goats, bearded and horned, comes past, leaping ahead of the goatherd along the sides of the irrigation channels. “To eat?” I ask the goat herd who followed behind. “Para leche,” he replies. For milk.

After several happy hours wandering I reach the front gate of Hacienda San Jose, a traditional Spanish colonial farming estate, approaching it from behind, catching glimpses of the archaic splendour of its painted mud mansion and porticos over the giant adobe wall that surrounds it.

Sitting in the shade of a group of molle trees outside I find several visitors waiting for the 11 am tour. A raspadilla seller with a cart is offering fragments of ice scraped from a giant block, and drizzled with honey and fruit juice.

“You should be careful walking round here, there are lots of morenos (darkies)” says a hard faced woman on the opposite bench. Her teenage daughter smiles happily, whilst their little dog, with a ribbon round its neck, scampers about. “Lots of darkies here, they will rob you and kill you.” The intense woman it appears, comes from Chincha – though not from El Carmen. Now they live in Lima, but they have come back to spend the weekend.

“I’ve been walking across the fields for two hours and had no problems” I reply.

“This place is full of darkies. You have to be careful,” she repeats, as if I may not have understood.

El Carmen, the village a few kilometres away, is indeed full of darkies. In fact that morning as I passed through in the taxi it had looked like the film set for a movie in Africa, black women with headscarves and brooms sweeping the dust from lanes with no cars but many dogs, banana stems by the roadside, flamboyant trees, tall black men shirtless, in cut off denim shorts, striding down the centre of the road.

When I visit later I find a pretty main square, with twenty giant palm trees flanking a red and yellow bandstand, a few stalls selling black dolls made of straw, with red polka-dotted skirts and head ties, locally produced wines and spirits, and bead bracelets.

El Carmen is the centre of Afro-Peruvian culture. One of the manifestations of that culture is “the longest Christmas party in Peru”. When I visited at the end of December I found the town was eerily quiet, as if the morning after a night of excess, and so it was. I met a local musician who apologised for his slowness. “We have had four days of music and dancing, from the 24th through to the 27th, 24 hours a day for those that can”. He was one of those that can, and must, be there throughout, as one of the town’s most famous fiddle players. I was reminded of Caribbean carnivals, Nine Mornings, where the ideal, for young men with something to prove, is to party till dawn for nine days and nights in succession. And still turn up at work each day.

The reason for this little piece of Africa in Peru, simply enough, is that these people are the descendants of the slave plantation of the Hacienda San Jose. Slavery was abolished by law in Peru in 1854. But the law is one thing and hacienda owners another. Twenty five years later, in 1879, as armed forces from Chile invaded during the War of the Pacific, the slaves finally seized their chance to escape.

The hacienda is now a hotel, charging 400 dollars a night and upwards to experience the ambience of an 19th century colonial slave plantation. It also offers guided tours of selected parts of the house and grounds, including the parlour with framed full length portraits of The Compte and Comptessa of Monte Blanco (“a little village in Spain” the guide explains) dated to 1702; the room where slaves were made to stand on one leg as a punishment (“a lot of them died”), and the chapel, built of adobe and roofed in cane, with a high ceiling and an ornately carved wooden altar piece, depicting several saints with their symbolic associations.

One of the principal attractions is the underground dungeon where the slaves, we are told, were kept blindfolded “so they could not escape”.

The hacienda had 1000 slaves, and was one of the richest in Peru. There were several plantations here, and Chincha was a centre of the sugar industry, when it was at its most profitable.

The haciendas were broken up under a revolutionary government in 1968. Velasco repossessed many of the large and unproductive landholdings and handed them over to worker co-operatives. Though the timing of the radical change accords with similar reform of land ownership elsewhere in the world, the surprising difference here it that the revolutionaries were a military government that came to power in a coup.

When I return to Chincha in the afternoon the streets are strangely quiet, the road past the hostal closed to traffic, the incessant parping of the moto-taxis’ horns sounding only in the distance. “They are reorganising the market,” the hostal manager tells me, “removing all the ambulantes and tiendas informales, street sellers. You should not go there, they are angry, it will be dangerous”.

I pause just long enough to collect my camera before heading to the market. The street is in disarray. Officials are directing the loading of planks, roofing sheets, glass display cases and sheets of wood and card on to the backs of open trucks. But the mood is practical. The stall holders are dismantling their own structures and carrying the components to the trucks.

As the view clears, it becomes apparent that the warren of stalls had hidden a broad street. The traders had built shops deep enough to park a car, and three metres high, out of wooden planking, sheets of cardboard, reed mats, and. whatever came to hand. Here they had been storing their wares while in the daytime they erected extra tables and displays in front of the storerooms.

With these structures on both sides, the two lane highway was reduced to a narrow passage through which moto taxis and pedestrians threaded uneasily. “It is a good thing” a chicha seller tells me. Like me and others, she is watching the scene unfold. “They have been here for years, blocking the street.”

The stall holders do not seem resentful or angry. Whilst some sit on their piles of card surrounded by bags of clothing, looking resigned, elsewhere there is a purposeful air as men climb aloft to take down their roofing or hammer at the concrete bases into which steel struts were cemented. It seems that their materials are being taken to another site, where they can re-establish their shops.

Back in Lima, I saw at first hand, whilst walking through the historic centre of town, how the city authorities handled a similar move to cut down on street trading. A group of eight policemen in a sealed van circled the streets. They wore protective jackets, helmets, visors, knee protectors, and carried truncheons.

Seeing an old woman selling cups of jelly from a tray, the van stopped, the door drew back, and all eight armoured police leapt out, surrounding the woman, snatching the tray from her and hurling the jellies to the ground. A bus going by slowed by the kerb, and passengers yelled at the police to stop. One of the policemen walked up to the bus, smashed the wing mirror with his baton, then attacked the bus window next to a passenger, showering him with broken glass.

****************************************************************

The following morning, I take a taxi to Huancor, once more. Secunda vez.

The modern road from Chincha to Huancor heads first east into the sandy foothills and winds through a rocky dry valley, up and over a 800 metre pass before descending to the San Juan River valley. Seven kilometres further through broad green riverside fields we reach an outcropping wedge of hillside where a dry valley heads north.

“Bienvenidos” – welcome –“ a los petroglifos de Huancor” says a green sign. “Cuidemos nuestro patrimonio cultural”. We care for our national heritage.

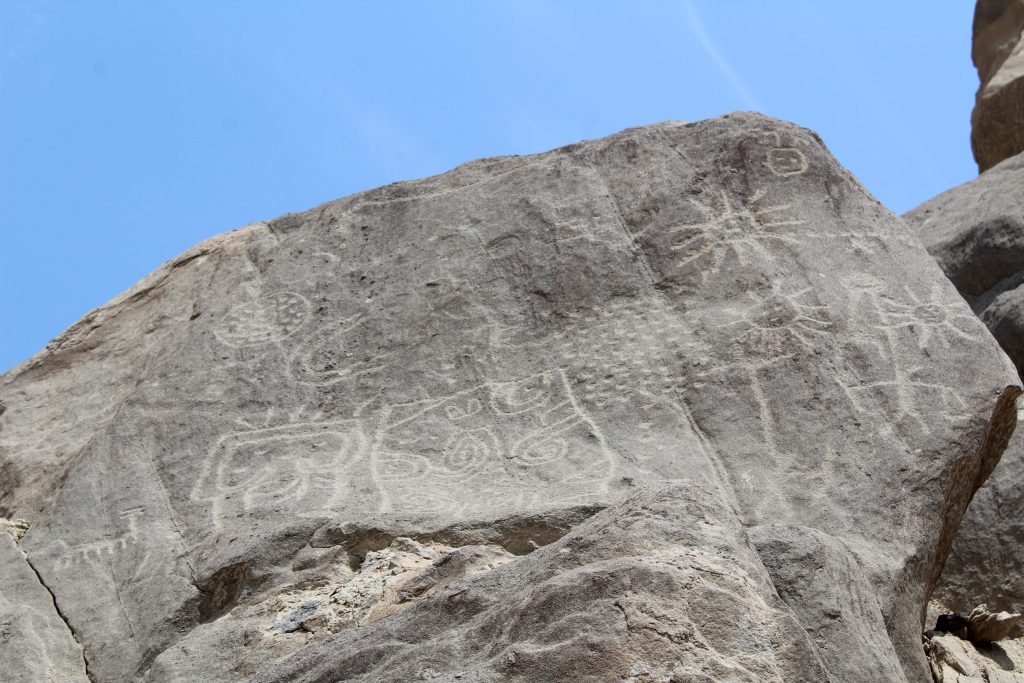

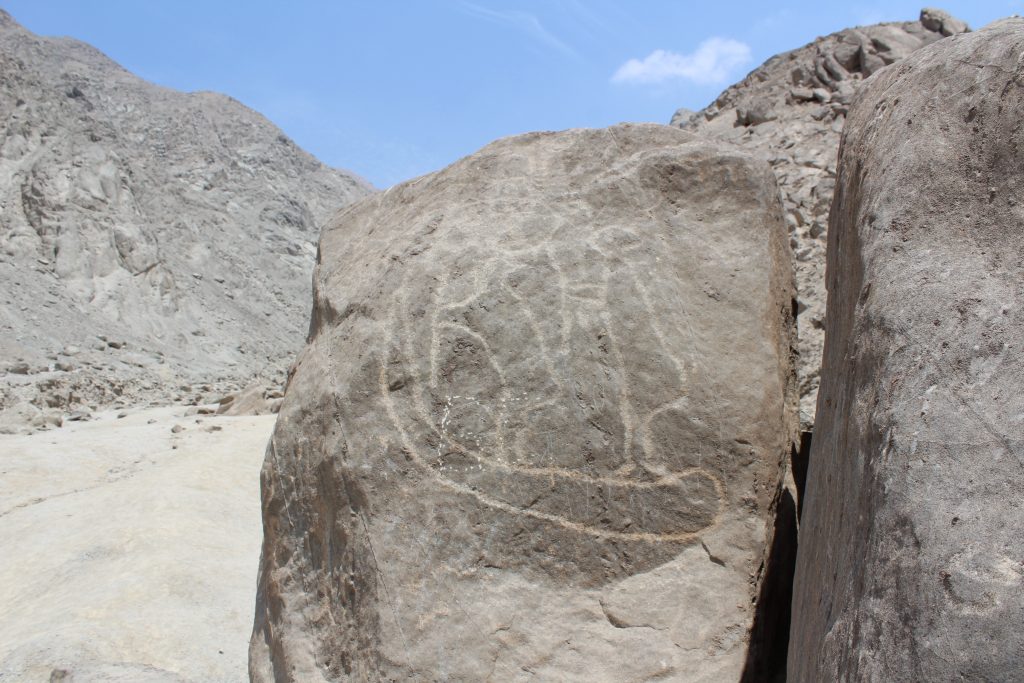

A path heads up from the road to skirt round the outcrop, and looking down on the path from slabs of stone slanting up the hillside to the right are several figures showing white against the dark brown stone. They stand in profile, holding to their mouths long pipes or tubes, instruments longer than themselves, with bulbous ends.

Similar figures have been called flute players elsewhere. They are seen at several sites in Peru including Yonan, Miculla and Toro Muerto. They have also been interpreted as people drinking, smoking, or inhaling hallucinogens. And I have seen similar figures on the rocks at Chincheros.

The path heads up past another sign reading “No destruyas los petroglifos de Huancor” and turns the corner into the dry valley. Above is a rocky promontory of tall rocks cleft with cracks, like a castle wall or a group of petrified guardians. Scrambling up I find a flat surface above these pillars of rock on the wedge of the hillside. Here there are smoothly worked depressions like grinding bowls, as well as grooves and swirls all cut into the rock. There are cupules too, deep and broad on upper surfaces.

I am looking down as if from a tower at the path below, the dusty plain towards the river, the valley extending on either side, and the grey mountains rising beyond. It feels like a centre point, with flat vertical rocks facing both West and South, towards the river and towards the dry valley. It is a spectacular, theatrical location.

Further up the dry valley there are more groups of stones, three or four flat vertical stones in an arc or looking down on a clear space, clustered with images. Behind one such group a higher rock bears the brightly cut name “Cesar”.

Beyond is a rock with a rounded head like a human figure, apparently naturally worn. Its chest is decorated with the figure of a man and two lines of four circles, and behind this rock are the collapsed remains of a mine entrance following a vein. Green copper ores are visible on small scattered stones around the shaft.

As I wander amongst the stones an elderly man appears walking up from a house down by the river, wearing a battered straw hat, sandals and a clean blue shirt. He approaches politely and begins to point out the designs on the stones. “Look there…a llama… look at the snake…”

He farms at the edge of the site and offers himself as a guide to the occasional visitors.

“What is your name?” I ask.

“Cesar”.

“Ah, I saw your name written on the rocks!”

He smiles modestly.

I give him ten soles to leave me in peace.

The markings on the stones at Huancor appear to have been made over a considerable period. The patina varies from bright white llamas and felines to abstract designs hardly visible against the natural rock. There are felines here in many forms and styles. There are long-tailed, sharp eared creatures, like fighting rats. There are man-lizards, climbing up the rock face. There are pecking birds with dotted bodies, giant insects, leaping monkeys, seated figures in profile with flying hair, crosses, a frog, lines and crosses of dots, wagon wheels, squares and circles filled with dots, cupule dots within circles, and dots, lots of dots.

One image here is particularly interesting, in view of Chincha’s history as a great sea-trading kingdom. The image stands out because of its size, half a metre tall, high up on one of the most prominent rocks on the site. It is finely drawn, delicate and clear, and shows two people rowing a totora raft. Such images are rare in Peruvian rock art. But it seems to portray a fishing vessel used close to shore, rather than for long distance sea trade.

There is one curious point of correspondence with the images further north. Huancor motifs include a large number of torc or horseshoe shapes, like a piece of metal bent into a U. A similar design appears repeatedly, nine times in all, on the hidden face of Paria Caca Rock.

It is interesting to note that the Chincha inhabitants of old called themselves the Jaguar people. There are many spotted felines drawn at Huancor, jaguars or mountain cats. I recall what Martin told me in Lunahuana – that the name means people of the guanay. The rock there is covered in images of these seabirds.

Perhaps some of these symbols, then, are like the U of Lima’s leading football team, left as a mark by their supporters on walls throughout the city. They could be the representative marks of a clan or tribe, an ayllu, or a religious group.

The tumi could be one such mark. The horseshoes, perhaps, represent an ayllu which took part in rituals at both Huancor and Conchineros.

****************************************

October 3 2018. Alberto Fujimori’s Pardon, his indulto, is reversed by the Tribunal Constitutional. The Judges vote six to one that the pardon was politically motivated, the alleged medical evidence of terminal illness was incorrect, and a pardon for Crimes against Humanity is unlawful under Peruvian and International law. Fujimori is rushed to hospital.

Monday 7 October

Congress approves the last of the four questions for the referendum. More than two months after they were submitted.

10 October 2018. Keiko Fujimori is detained by police as part of an investigation surrounding the Odebrecht scandal and money laundering allegations that involved her 2011 presidential campaign. She is released from detention a week later on appeal. The prosecutor however launches a new request for detention, this time for 36 months.

*****************************************

Thursday 11 October 2018. Congress debates a new law to free elderly people from jail. A special dispensation is signed by three Congressistas at 9.50 in the morning to enable the law to proceed direct to final debate without any previous discussion at committee stage. The law is passed on a first and second vote at 17.50 pm. It appears that it will apply to Alberto Fujimori, but it will need the President’s signature before becoming law.

Friday 12 October 2018. Fiscal Pedro Chavarry sacks one of the lead prosecutors working with Domingo Perez on the Cocteles case against Keilo Fujimori. Erika Delgado was investigating the case as it related to former president Alan Garcia.

***********************************

17 October 2018. The Minister of the Interior announces that senior judge Cesar Hinostroza has fled the country. He escaped through a remote border crossing into Ecuador.

The security camera at the border post shows a man walk up to the counter and talk to the immigration officer. Hinostraza then enters looking nervous whilst the first man keeps watch. The officer looks at his passport but does not enter the number. This would have set off an alarm, as the order to stop his leaving the country, issued three months earlier, has been implemented on the national control system. It later emerges that the officer enters her own identification number, and then deletes it.

The officer was moved to the control point from an office desk job the day before Hinostraza’s arrival. The manager who moved her is the wife of a Fuerza Popular Congressman.

It later emerges that the immigration officer who let Hinostraza leave the country allowed a multiple murderer to leave the country a year earlier. The twenty year old Columbian had killed and robbed three money changers on the streets of Lima in the space of a few weeks. He was imprisoned but released three years later and he passed through the same border crossing into Ecuador in 2017.

19 October 2018. Fleeing ex-Magistrate Cesay Hinostraza is detained north of Madrid. He is jailed in the Soto del Real until his extradition to Lima.

The same day, conversations in a whatsapp group of leading Fuerza Popular members called “La Botica” are revealed on Twitter. Keiko tells the President of Congress, Daniel Salaverry “send message to the group saying Chavarry is a correct guy and the caviars are making mountainous accusations…” OK says Daniel.

Keiko’s adviser Pier Figari says of the Fiscal Domingo Perez, who heads up the Cocteles investigation into campaign financing of FP, “with the doc in hand we’ll give interviews and fuck him, delegitimise him, show he was acting out of hate and without any real investigative aim.”

“Absolutely it is a brilliant opportunity” replies Hector Becerril.

*****************************************

22 October 2018. Fiscal Lourdes Tellez calls Domingo Perez to present himself at 24 hours notice to explain the appointment of his wife in 2017 to a position as Director of a department of the Ministry of Economy and Finance.

He replies that she should ask his wife.

The same Fiscal, seven days previously, asked Domingo Perez to present himself and justify his speech to a conference on corruption in Mexico.

Domingo Perez is in the process of preparing a briefing against twelve alleged members of the criminal network within Fuerza Popular and their lawyers, due Wednesday morning. On Sunday the presiding judge asked for specific cases to be presented against each rather than one broad case against the network. So he is little busy, in his primary job as fiscal, fighting corruption in Peru.

**************************************

23 October 2018. President of Congress and former FP spokesman Daniel Salaverry asks to have a temporary leave of absence from the party “to protect the independence of the position.” Three other representatives offer their resignation.

24 October 2018. It is revealed that FP Secretary General Jose Chlimper has also resigned, a week after the investigation into the faked tape he supplied to a TV station was re-opened. The investigation had previously been archived by a judge in May 2018. On the same day, Fiscal Perez says that Odebrecht witnesses state that Chlimper was given $210,000 in cash to support FPs election campaign. He paid $210,000, also in cash, to the Director of TV news channel RPP in May 2011.

Keiko Fujimori pledges a new dialogue with the country.

The next morning Rosa Bartra threatens to sue the fiscal, whilst Keiko says that the fiscal has presented a series of lies that have been demolished by her lawyer.