I hear of the “discovery” of a petroglyph in the lower valley of Cañete, close to the town of Lunahuana. There is a blog, and a photograph, and just one image from the rock, something like a rodent or a squirrel. Like the bird images of Cochineros, it is beautiful and highly stylised, as if copied from a woven textile or a ceramic.

Cañete, the modern town in the coastal plain, is sufficiently large that I have to take a minivan from the bus station on the coastal road to the other side of town, twenty minutes side-winding through every back street neighbourhood, to Nuevo Imperial, the junction for traffic up the valley.

The town of Lunahuana is some thirty kilometres upriver. It stands on the left bank, high above the irrigated fields. It was badly damaged by the earthquake of 2007, and many former houses still lie in ruins. Just six blocks wide by six blocks long, the town is similar to many spanish reducciones in the coastal valleys, with a colonial centre – church, square, municipal offices – surrounded by a grid of streets and then farmland, in a valley dotted with the ruined villages of a more populous time. By some happy combination of position and climate, it has become a tourist mecca.

The first full moon after the autumn equinox in South America, also known as the Easter Weekend, is a national holiday, and every year thousands of tourists head to the town to enjoy white water rafting, eating in the town’s several restaurants, drinking pisco sours at the makeshift bars set up at the side of the pretty central square with its bandstand, flowering trees, and ornate cast iron street lamps, or barbecuing meats besides the swimming pool in the more luxurious hotels. The hostals and hotels fill all their rooms, and charge double the normal rates.

Lunahuana is two or three hours from Lima, for those with private cars. Some time after 9 am, the tour agencies open their doors, start up their big screen promotional videos, and stand in the street with hand made signs ready for the tourists.

Forty minutes after leaving Cañete, I climb off the bus. Normally I would be be greeted by a line of youngsters waving placards at me and shouting “canotaje!” canoeing! Down by the river bank, inflatable rafts would be coming in to land one after another, every minute or two, after shooting the rapids. But there is no rafting now on its swollen, swirling waters. There are less tourists this year, but they have still come – roads to the north and the east of Lima are impassable – to try zip-lining across the foaming river, quad biking on dirt roads behind the town, and rappelling.

On the street two women wearing red and black chequered cloth tied at the waist with a woven belt are selling vegetables. This is the clothing of communities in Yauyos, upriver and inland. In this protected reserve a few hundred people still speak Jaqi, an original form of Aymara. These are the people whose traditional dress on special occasions includes a pair of silver tupus worn on the chest, with the rounded end down. The people that me and Mayra planned to visit.

“How far have you travelled?” I ask.

“Three hours, from Catahuasi,” they tell me.

I buy a matured cheese “a week old, and it will be good for another week” and a small dark avocado.

“One day I will come and visit Catahuasi,” I tell them.

“Come on a Sunday, we will be at home then,” they reply.

The main road to Lunahuana stands high above the river and couples lean on the white wall watching the zipliners take off from a wooden deck built out over the drop. Four flights of steps zigzag down to the river bank below. A large field besides the river offers camping to visitors, and a low stone wall separates it from the neighbouring farmland.

The petroglyphs here were “discovered” in 2014, but the giant boulder is in the centre of the field below the zipliners as they buzz past, and in view of the roadside wall where the couples lean. Further down the road is a freshly painted signpost announcing the graven stone. Below the signpost a field of recently harvested maize stretches to the river, and I can see the upper surface of a boulder rising above the broken stalks.

I follow a steep footpath down the dusty slope of scree, across an irrigation channel and down past a dry stone wall which borders the camp site. The field is a series of terraces held up by andenes, ancient containing walls, two metres high, constructed of river boulders. On the edge of the third andene is a giant river-smoothed rock, one side on eye level facing the top of the terrace and the other dropping steeply to the lower level.

I am standing in front of a massive and outstanding stone, a sloping ramp of smooth dark grey rock, with two great white veins of quartz, and numerous cracks, pointed south west, downstream. It stands several metres above the river today, but it is rounded in wave-like contours. It is easy to imagine how the roaring winter floods, loaded with gravel and sand, could have rushed around and over it, wearing it smooth.

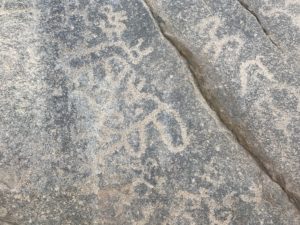

On the main panel rising in front of me I can see two exotic birds, curly tailed with big open rounded wings. They are similar in style to the fantastic birds at Cochineros.

There are many more simpler stylised birds scattered across the panel, all with the same essential characteristics, a head, an open beak, two wings. They resemble a common motif on weaving from the late intermediate period, found in textiles from Chancay and throughout the central coast down, and yet hardly any two are identical.

I can see other motifs too – a square filled with dots, seven or eight camelids dispersed, and felines, like squat terriers, with aggressive heads. The panel is topped off with two more beautiful birds, in the familiar textile style, and yet each individual.

This face slopes gently upwards, and I clamber up the stone to its peak, which drops away steeply on the other three sides.

The imagery becomes more complex towards the top. In a hollow below the peak is a beautifully drawn, stylised quadruped with a curling tail, a pointed nose and open mouth. It is centrally placed, dominating the rock when seen from the hillside above.

The top of the stone is covered with more sea birds and dot patterns, and a representation in stone of a well known woven textile design, a diamond with crenellations surrounding a fish. In a depression below the peak are three finely drawn felines. They show the classic glare of a startled puma surprised crossing the edge of a field, its body moving away but its face fully turned to stare, two ears upright. The image is distinctive enough today to anyone who cares for domestic cats. But each of these felines drawn close together on this high ledge has their own distinctive style.

On the south face, in the uppermost corner, there is a flight of geometrical birds. Their wings, tail and head are represented as four triangles meeting at a central rhomboid, the body. This image too is familiar from painted textiles found at Chancay.

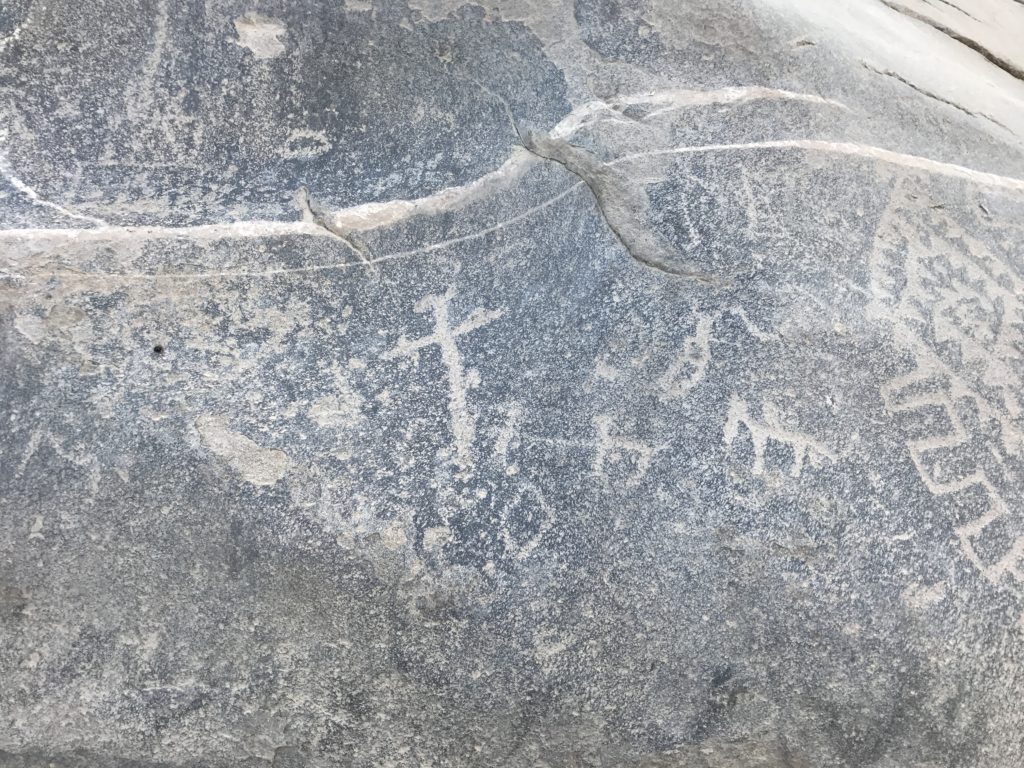

Down at ground level is another woven textile design of crennellated diamonds, and to the left of it is the unmistakable mark of the conquistadors. The small figure of a man on horseback, a tall cross, or perhaps a sword, a long vertical blade with a horizontal arm, and above and to the left, faintly, a colonial image of a church, with a base, an upper arch and then a tower.