At the first full moon after the autumn equinox in South America, known to some as Easter, I return to Lunahuana. The water is still too high to cross the Rio Mala, but in this neighbouring valley, I can take another look at the giant boulder in the field beneath the zip wire.

The coming Monday would be a holiday and thousands of tourists had headed to the town for the long weekend of white water rafting and zip-lining, eating in the town’s several restaurants, drinking pisco sours at the makeshift bars set up at the side of the pretty central square with its bandstand, flowering trees, and ornate cast iron street lamps, or barbecuing meats besides the swimming pool in a couple of the more luxurious hotels.

The manager at my usual hostal tried to double the room price, before I reminded him of what I had paid a few months earlier. Down but not out, he offered me a room at the top of the building “with a magnificent view” which, I realised too late, was unsufferably hot in this April weather.

On the street two women wearing red and black chequered cloth tied at the waist with a woven belt are selling vegetables. This was the clothing of communities in Yauyos, inland to the East, mountainous and remote, now a protected reserve, where a few hundred people still speak an original form of Quechua, and continue their traditional ways.

“How far have you travelled?” I ask.

“Three hours, from Catahuasi” they tell me.

I bought a matured cheese “a week old, and it will be good for another week” and a small dark avocado.

“One day I will come and visit Catahuasi” I tell them.

“Come on a Sunday. We will be at home then”.

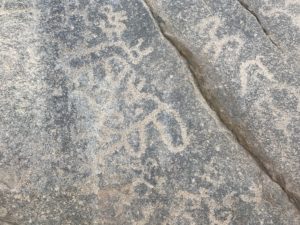

I go down in the afternoon sun to take another look at the stone. The crop of maize that had stood above my head was all gone, with piles of ash across the furrowed field where the stalks had been burnt. The great stone could be seen clearly now, a sloping ramp of smooth dark grey rock, with two great white veins of quartz, and numerous cracks, pointed south west, downstream. it was easy to imagine how the roaring winter floods, loaded with gravel and sand, would have rushed up that ramp, wearing it smooth, before cascading down the vertical lower face. Several of the Cochineros rocks had the same shape, a gentle slope upwards and then a drop.

Viewed from the ground, the ramp seems to divide into four panels, defined by the shapes of the boulder itself. The face leading upwards was two metres wide, with cracks and folds. The rock climbs ahead in waves.

The main panel rising ahead has two exotic stylised birds, curly tailed with big open rounded wings. Above and to the left is a square filled with random dots, and above that a diamond. To the left, another diamond containing six dots and around it seven or eight quadrupeds dispersed, a one finely drawn young llama, others more feline, like squat terriers, with aggressive heads. The panel is  topped off with two more beautiful birds, in the familiar textile style, and yet each individual.

topped off with two more beautiful birds, in the familiar textile style, and yet each individual.

The panel to the right, worn and fragmented on the top, has several llamas, large and small, one above the other.

Moving round to the right, another panel of the rock shows a simple figure of a man, facing out, with arms oustretched. Above him two llamas back to back, with possibly two young llamas amongst them, and then a pair of llamas joined by a rope, neck to neck.

Climbing up the smooth inner slope of a fold in rock, another panel becomes visible, with several llamas, drawn square and fat, like highland terriers, minimal short straight tails slightly raised, in profile with two legs.

By scrambling up further that I can see the rock flattening out towards its peak and here, larger and clearer than any of the lower images, dominating the rock, is a beautifully drawn, stylised quadruped with a curling tail, a pointed nose and open mouth. This could be a fox, or a squirrel, a full half a metre long. It is difficult to see from ground level around the stone, but can perhaps be seen from higher up the hillside, looking down onto the top of the rock.

The very top of the stone is most intensely covered, with a pattern of dots on the flat surface at the very peak, and a textile diamond with crenellations and a fish at the centre right on the edge, several sea birds scattered around, a deeply grooved line, slightly curved, running from left to right. On folds and sloping panels falling away to the right there are more stylised sea birds, three in a row, leading towards two human figures, standing in profile, with rods in their hands.

Below ware three finely drawn felines. They show the classic startled puma, surprised crossing the edge of a field, its body moving away but its face fully turned to stare, two ears upright.

The image is distinctive enough today to anyone who cares for domestic cats. the animal moving away or parallel, but turning a full face and intent gaze towards you. But each of these three felines drawn so close together on this high ledge, have their own distinctive style. Three artists, undoubtedly, and probably at different times.

Slipping and sliding back down to the ground I circle the rock. Nothing is visible on the vertical northern face towards the river, under the shade of a molle tree, while the western drop has a couple of initials of indeterminate age. The south face, accessible from the upper terrace of the andene, has several isolated llamas, a feline, more stylised sea birds, and in the uppermost corner, a flight of geometrical birds, four triangles meeting at the  centre, representing two wings, a tail and a head. The image is familiar from ceramics, and particularly from painted textiles found at Chancay, a few hours north of Lima, which are said to be of Wari production and representing their cosmology.

centre, representing two wings, a tail and a head. The image is familiar from ceramics, and particularly from painted textiles found at Chancay, a few hours north of Lima, which are said to be of Wari production and representing their cosmology.

The Eastern side, neatly divided by a white mineral vein running in an arc the length of the stone, has a fish low down to the ground, and more stylised felines, with sharp ears and curling tails, one apparently unfinished.

To the left of these is a wonderful textile design, a diamond of crenellations, wound on itself to form a three level spiral. The top and bottom corners of the diamond are finished off with typical weaving features, a pair of triangles below and a dotted eye above. From one perspective it is a simple geometrical design, though complex. But it could also be a fish, with another fish within. It is flanked on the right with another geometrical design, a reversed capital E, the lower limb having hanging tassels.

And there in the centre of the southern face, is the mark of the conquistadors. A tall cross, a crucifix, or perhaps a sword, a long vertical blade with a horizontal arm, with to the right, the small figure of a man on horseback, and to the left, faintly, a colonial image of a church, with a base, an upper arch and then a tower.