Back in Lima I visit the library to see what the chroniclers have written about the pre-hispanic road networks in Peru.

Inca Garcilaso de la Vega was born just 17 years after the Spanish invasion from an Inca princess and a Spanish fighter. He starts his masterwork, Comentarios Reales de los Incas, by describing how his mother’s relatives would visit. “On these occasions, the conversation turned almost invariably to the origin of our kings and to their majesty. It also concerned the grandeur of their empire, their conquests and noble deeds, their government in war and peace.”

So his is not an independent voice, but he is honest about his sources, and his writing runs through with both pride and a sense of loss. “Being but a child, I came and went freely among them, and I listened with the rapt attention with which at this age one listens to fairy tales.”

When he comes to describe the Inca roads, he chooses to quote others. “These roads constitute such a gigantic achievement, that no single description suffices to describe them.”

Augustin de Zarate describes how Inca Huaina Capac constructed “…a great wide highway, all along the the cordillera. To do this meant razing peaks and crests, or elevating the roads above chasms and valleys, by means of stone walls that sometimes reached fifteen or twenty stades [one stade being two metres]”.

And on the coast “…the indians cleared all…obstacles and succeeded in building a road that was perfectly uniform and continuous, well banked on both sides, and forty feet wide…one had to pass through vast stretches of sand constantly being shifted by the wind…” The indians marked out the road through the sand by poles planted at intervals. “Today most of these poles have disappeared, because the Spaniards used them to make fires, but the roads the indians built across the valleys are still there.”

And Garcilaso can not resist adding his own poignant commentary.

“None of all this has resisted the ravages of time and war, and today almost nothing remains. Along the coast too, the only things left, the merest memories of the great highways of old, are the poles protruding here and there from out the wind-driven sand, to guide the traveller and keep him from losing his way.”

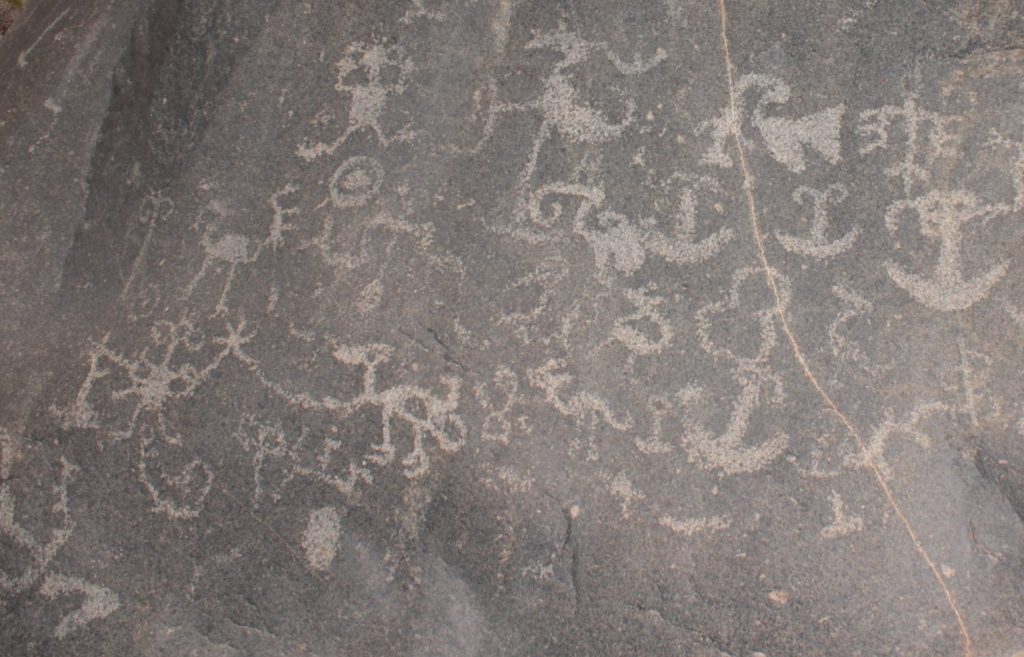

This is wonderful, sonorous stuff, and there are, in places, the tracks of the roads to demonstrate all that was said. But I understand now that there were thousands of years of different cultures and peoples, on the coast and in the highlands, before the Inca, each with their own ceramics, building styles, weaving and road systems. And the archaeological record – ceramics, textiles, and petroglyphs – shows us that the ideas, the icons and the technologies of these disparate peoples were spread and shared.

************************************************************************

Ceremonies of sacrifice and divination using llamas are described in detail by sources from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, such as Pablo Joseph de Arriaga in his Extirpacion de los Idolatrios.

“The llama is sacrificed during the festivals of the huacas. They bring out an animal garlanded in flowers, tie him to a great stone, and make it go around five or six times. Then they cut open his left side, take out the heart, and eat it raw by the mouthful. They sprinkle the huaca with the blood and divide the meat amongst the priests. In some places they raise young llamas especially for the huacas.“

” They… eat it raw by the mouthful” is not something recorded in any other account of the sacrifice. But this particularly grisly description is from a Jesuit who was writing with glee of his work persecuting traditional religious belief. He dedicated his life to denigrating native practices, and is as unlikely to have observed these rituals personally as a nazi is to have seen a bar mitzvah.

Less tendentious sources explain that the rite involved studying the entrails and particularly the lungs to learn about the future. Garcilaso de la Vega supplies a detailed account describing the divinations at Inti Raimi, the most important of Cuzco’s four annual festivals, the June Solstice.

“The priests brought in the animals to be sacrificed, which were lambs, rams and sterile ewes. The first animal sacrificed was either a black or dark brown lamb, these being considered…entirely pure and unmixed. They looked for omens by examining the heart and lung of this lamb, as they did in all important circumstances…Three or four men held the animal with its head turned towards the east…they then slit it open on its left flank…and the priest took out the heart, lungs, and all the interior organs, taking sure that they should be in one piece, without being torn…they would blow air into the viscera, then…watch the way the air filled…the lungs even unto the tiniest vessels…the sacrifice of the lamb, if it did not give good omens, was followed by that of the sheep and lastly, that of the sterile ewe.”

Pedro de Cieza de Leon describes something similar in the village of Lampa, in 1547, as written down by the priest who observed it. At the full moon in May all the headmen visited him to ask if they could carry out their customary rites. At noon to the sound of drums, a young boy and girl, dressed in gold and silver ornaments and red tassels, the girl wearing a puma skin, came and bowed to the headmen who were seated on cloths on the ground, “their hair hanging in a four strand braid on each side, as is their custom”. The children were followed by six farmers with ploughs and bags of potatoes who performed a solemn dance.

“When this was finished … a yearling llama was brought in, uniform in colour, without a single blemish, … they stretched it out on the ground and while still alive, removed all its entrails through one side, and gave them to the soothsayers … certain of the indians scooped up as much of the llama‘s blood as they could, and sprinkled it over the potatoes in the bags …”

The ceremony was interrupted by a headman “. . . who had turned Christian a few days before … rushed forward shouting and calling them dogs . . . shouting still louder he upbraided them for that diabolical rite. As a result of his reproaches they went away frightened and confused, without completing their sacrifice.”

Both these sources are talking of Inca ceremonies. When the Incas came to the coastal valleys of central Peru, around 1470, they established a place to pasture the llamas for sacrifice to Paria Caca, and to Pacha Camac, at Sucya Villca.

The Huarochiri Manuscript says that the Inca paid, or supplied, thirty priests to attend to Paria Caca, “The llamas of Pachacamac sent from the Checa people stayed at Sucya Villca.”

This Sucya Villca was by a lake on the hills above St Bartolome (modern Matucana), according to noted Peruvian researcher Maria Rostworowski.

The Checa people were presumably based in what is now St Damien de Checa, fifty kilometres to the north, but it may be relevant that there is a modern village a few hours walk up river from Conchineros, called Checas. And on a plateau above today’s few houses there are the ruins of a large pre-Inca settlement.

“Paria Caca established his dwellings on the heights, and began to lay the rules for his worship. Once every year you are to hold a celebration re-enacting my life,” the Manuscript continues.

“People go to Paria Caca to worship. In olden days they used to go to Paria Caca mountain itself. But now they go from Checa to a mountain called Ynca Caya. People run on their way to this mountain, driving their llama bucks. The strongest ones even shoulder small llamas. They scramble upwards, each thinking ” I mean to get to the summit first!”

“The Yunca people from Colli Carhuayllo, Ruro Cancho, Latim, Huancho Huaylla, Pariacha, Yañac, Chichima, Mama, and all the other Yunca from that river valley, also the Saci Caya, and the Caring and the Chilca, and … the Caranco used to arrive at Paria Caca itself, with their ticti, their coca, and other ritual gear…”

In one of the closing chapters of the Huarochiri Manuscript, the 30 men who served Paria Caca according to cycles of the full and waning moon sought an augury.

“They sacrificed one of his llamas, a llama named Yauri Huanaca. When…they examined the heart and entrails of the llama, a fellow called Quita Pariasca the Mountain Man spoke up and said “Alas brothers, the world is not good! In coming times our father Paria Caca will be abandoned.”

“No” the others replied, ” you are talking nonsense!”

“It’s a good sign!”

“What do you know!”

One of them called out “Hey Quita Pariasca… in these llama innards our father Paria Caca is foretelling something wonderful!” But he had not even approached the llama to inspect the augury. He was watching from afar.

The mountain man rebuked them. “It is Paria Caca himself who says it, brothers.”

They talked in great anger, deriding him with spiteful words.

“What does that smelly mountain man know!”

“Our father Paria Caca has subjects to the limits of the land of Chinchay Suyo. Could such a power ever fall desolate?”

But just a few days after the day when he said these things, they heard someone say “Viracocha [spaniards] have appeared in Caja Marca.”

*******************************************

F. 16 Nov 2017

Canella explains Keiko Fujimori to me. “This woman, who has never had a job beyond leading her father’s party, has the country in her hands. She controls her congress majority like puppets and now seeks to sack judges who want to investigate her campaign funds. She can do this because the constitution was written by her father.”

10*************************************

December 7th 2017. The fiscal (state prosecutor) enters and searches two locales, party offices, of Fuerza Popular. Several computers and files are removed for examination. In the following hours the response of the FP spokesmen is prominent in the news and on the web.

Javier Velasquez Quesquen of Fuerza Popular says “we are living in a stellar moment of destruction of institutionality”.

“This is a total abuse” said Daniel Salaverrry, “We have never been in government. Where are the raids on those that have been in government all these years?”

“It is a violation of human rights” says Lourdes Alcorta.

Four members of the political party were photographed by the press arriving at the Surco party office shortly after the investigator’s raid began. They were Rosa Bartra, Daniel Salaverry, Luz Salgado and Jose Chlimper.

Rosa Bartra was put on the defensive by calls for her resignation from the Congressional Committee investigating Lava Jato. “As president of the Lava Jato Committee she should not be interfering in the Fiscal’s investigation”. She later explains that she was called to a meeting and did not know the fiscals were present.

Keiko herself speaks to the press late at night and said there was an “abusive” and “vengeful” attitude from the public ministry. “I reject the outrage that the fiscal has done”.

El Comercio dedicates its front page to a photo of the FP press conference which features Keiko Fujimori in front with thirty members of her party standing ranked behind her, with selected quotes from the party spokesmen about the “outrage” and “abusos”.

The fiscal explains that the Judge Concepcion gave written consent for the raid as there was evidence of double book-keeping. The party resisted handing over its books despite repeated requests and finally presented legalised copies but not the originals on 11th October.

The legalised copies did not match the originals which the fiscal inspected on 24 November. A legal notary recorded 14 books of accounting records, whereas the party only supplied eight books.

Columnist Augusto Alvarez Rodrich writes in his column in La Republica, “Peru has become a Roman circus that will end badly. This farce called Peru is in a march of madness that is going to get worse before improving and that can explode at any time.”