In simple terms

There is visual evidence of brighter and darker images on the same panel. There is variation in Brightness.

There is visual evidence of brighter images overlaying darker images (heart – spiral, tupus-old llama, dots- trumpeter,

The overlay suggests brightness correlates with age.

On some panels, though others show no apparent brighness.

The image brightness can be measured quantitatively, in a variety of ways, at different times of day and year, at different angles to the rock face.

The quantitative brighteness could be correlated quantitavily with age.

The change in image brightness, measured at different angles, times, dates and jpg v Raw as above, gives consistent straight line results, ie it is a robust measurement

postulate rock varnish as the mechanism for change.

Sup

There is Visual evidence for rock varnish formation at the site ( examples waterfall P1, dots P2,

Evidence for variation in rock varnish growth rates, is visible.

supported by panels with little or no variation.

Explanation for s and n and river panels variation

As a trial of the dating we will concentrate on one panel, which is inclined at and oriented.

There is visual evidence of consistency in the brightness measurement from top to bottom, on one panel, from dot trail, and left to right, eg from heart and JMJR, at creation, and for consistent fading….eg brightness of old images on Piedra 6, old images on P11, exceptions the left hand lobster. Sufficiently covered with images that any major discontinuity can be seen.

The evidence of eg P1, P4 in fact strengthens -in that discontinuity is obvious, so we do not attempt to date on those panels.

P6 we have spiral, tuyantisuyo, running llamas, all showing vertical and horizontal consistency

There is visual evidence of consistency from left to right, on one panel.

A straight line assumption gives consistent dates for

The theory that rock varnish formation is reducing the image intensity would account for an exponential change which gives similar results, for newer, brighter images, and somewhat older results for darker images.

Estimates of the rate of rock varnish formation, although they vary somewhat, agree with the findings.

Another larger panel inclined to the NW is less accessible to photography. It has a similar dark and light images, with the dark images barely visible under normal illumination, becoming visible when the sun is low.

The white imagery and the dark imagery are as shown.

The panel is now not accessible

The river facing side of Piedra 6 is not accessible. It appears to be almost entirely dark images, with the exception of tumis and tupus which perhaps could have been drawn from above. with access from the upper terrace.

The dating suggests the dark images are 1500 to 2000 years Before Present, and therefore 1000 to 1500 years older than the most recent historic images, ascribed to the time of the Huarochiri Manuscript and/or Inca period on conceptual grounds.

The dark imagery differs in subject matter, and some stylistic ways. The bright and dark imagery represent two phases of the use fo the site. The bright imagery in turn has a history of perhaps 500 years.

The combination of stylistic and image brightness criteria allows a picture to he built up of multi-cultural use of the site over a long period of time.

The technique could be applied to other panels if images could be recorded using drones or rock climbing.

My first attempts to derive some quantitative estimate of age from the brightness of the images on the rocks of Rio Mala used the Kubelka Munk theory for a thin layer of material described by its coefficients of absorbance and scattering.

If the white image is due to a coating of fractured crystals, on top of the darker rock, then this theory may help us understand what we see in the layered images of the stones.

We saw that although over certain limited ranges the relationship appeared linear, it was wildly non-linear across the full range of reflectance from up to 0.8 (80%) or 0.9.

The reason is essentially that like adding coats of white paint to a dark surface, the colour of the surface will brighten, and for low opacity paint in thin layers, the change will be apparently linear if it is small. If one coat of paint gives you 2% whiteness then twenty coats will give you 20% whiteness. But 200 coats will not give you 200% whiteness, and after a certain number of coats, say 50, the surface will be uniformly white and bright and adding further coats of paint will make no difference.

As we are looking at the reduction in brightness from the erosion of the fractured crystal surface, we do not know, to continue the analogy, if the bright white JUAN is formed of 50 or 200 coats of paint. If the latter, it may remain bright and white for four hundred years, as 150 coats of paints are worn away by the wind and rain, and then begin, apparently suddenly, to deteriorate. So even if we could justify applying Kulbelka-Munk theory to the images, it would not allow us to calibrate the brightness with age without a much better understanding of the process.

The realisation that the images are being covered in rock varnish changes all this. If we postulate that the images are fading not because of erosion of a white layer, but by growth of a dark layer of rock varnish, then we have a scenario that is in a sense reversed.

At the start of our measurement back in time, we will get a gradual incremental loss of brightness, due to the growth of a very thin layer. As the image brightness changes by small percentages, from 220 to 215 to 198, if we are looking at jpeg readings, we will initially see a nearly linear relationship, like adding almost transparent coats of paint, or varnish. Later on, when the fresh white markings on the rock are entirely obscured, long periods of time may pass with little evident change in the image. The winds and rain and moisture on the riverbank are adding more layers of varnish, but it no longer changes the colour. What it may change is the texture of the surface.

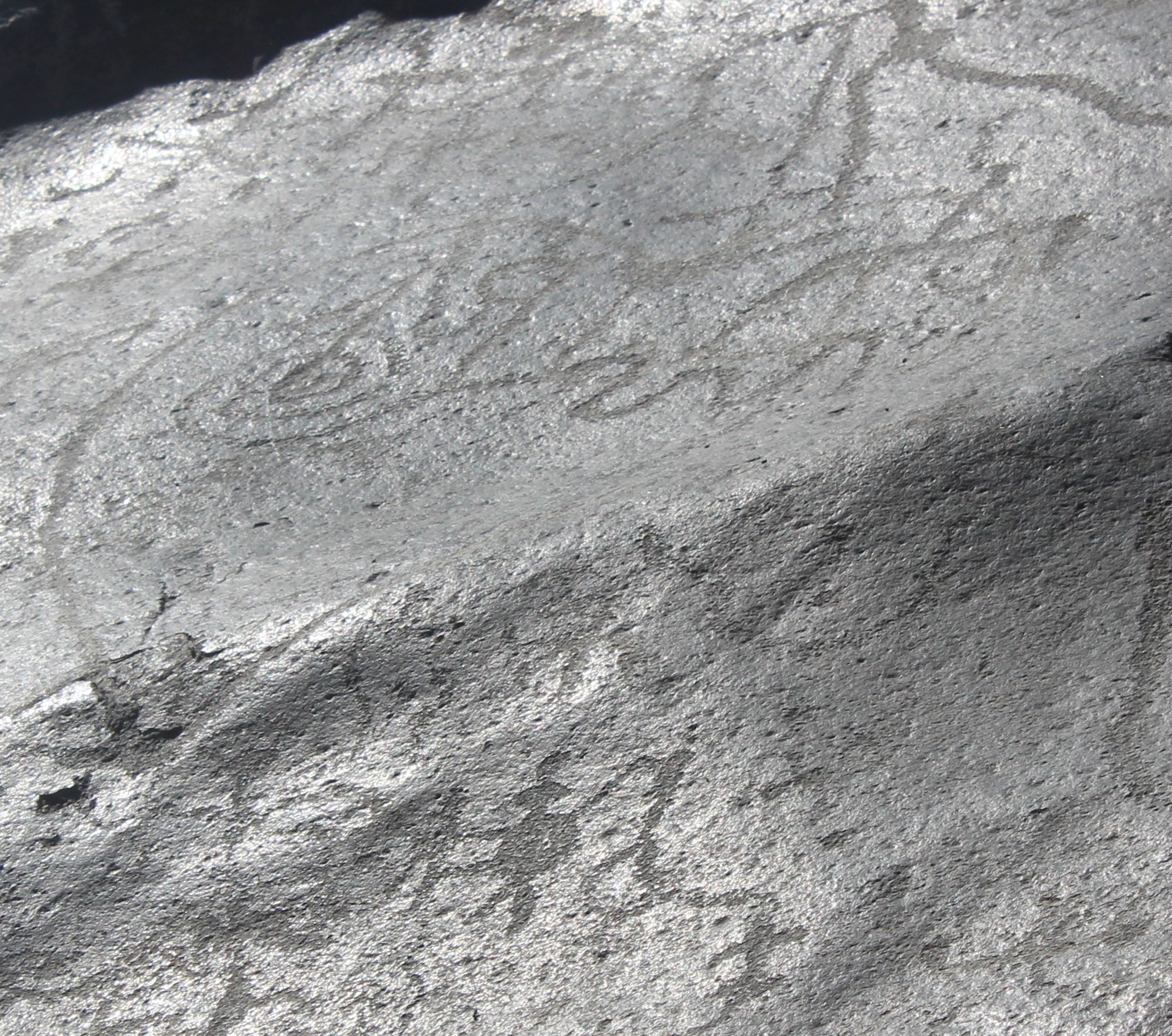

Looking at the rocks, we can see effects that would be explained by this. There are images which are almost the same colour of the background rock – older even than the old llama. To see them clearly we have to position ourselves low down and look at sunlight reflecting off the surface, because the varnished surface is smooth and shiny, whereas the broken surface, though now dark, remains pitted and rough.

if two hundred years of varnish reduces the brightness by 20%, then it might seem that one thousand years will reduce it by 100%. It is of course not so simple. The first 200 years reduces by 20% of 100%, the second by 20% of 80%, or 16%, and the third by 20% of 66%, or 13%. Again we have an exponential curve. But now we can say, that if the brightness is reduced to (approximately) zero, then it is older than the 1000 years. We have a minimum age. And as we look at the rock face of the Rock of the Tumis, or Pariacaca Rock, in the slanting light of the northern sun in early July soon after the solstice, we see that there are a great many dark, hidden engravings. We could conclude then that the dark art here, barely visible, dates to more than one thousand years ago. As others have suggested from reviewing rock art across Peru, such engravings are largely abstract, geometrical. It is the later, white engravings that represent birds, or foxes, or tumis and tupus.

Our first brightness measurements, on the Paria Caca Rock, found the heart had an average brightness of 207+/-4, and the dot track averaged to 195+/-5. The unmarked rock had a brightness of about 140. Using the above argument, and assuming the dot track is 500 years older than the heart, gives us a minimum age for those dark, hidden engravings of as much as 2500 years, or perhaps as little as 1200 years.

In the meantime, without being able to give a quantitative age to any of these markings, we can place them in a herarchy of image brightness, from the jpgs images, which we could convert to a reflectance hierarchy with some appropriate conversion. The order would be unchanged. We can do this for each individual rock face, where the photographic image was taken at the same angle and with the sun at a sufficiently oblique angle to the face. This may give us a series of image strata, that perhaps we can compare.

The absorption depth for Manganese Oxide, is 10-4 cm, or 10.6 metres, 1 micron. This is the depth at which 36% of the light is absorbed. The data for the old llama suggest that it has 60% of the brightness of our spanking white heart, so that one third of the light is absorbed. If the light then is passing through an absorbing layer, it is half a micron thick – a micron for light going through the layer and reflecting back again. The estimates of rock varnish growth suggest an average rate of 1 micron per thousand years, though it can differ greatly from place to place and even in one place. If a rock varnish layer of black Manganese Oxide is responsible for the dimming of the images of the rock, the observed effects are perfectly compatible with our dates – the old llama is 500 years old, and has a rock varnish layer of half a micron.

With bright light hitting the rock surface at all angles, for example from a cloudy sky at midday, we only see the bright white marks which appear to be the latest additions to the panel.

With a cloudless day the main light on the rock is direct sunlight, and by standing at angle to the rock face so we do not see the glare from reflected light, we can see that the heart is drawn over a spiral with a serpentine tail. There is also a line of dots within the heart on the right hand side, and lines and figures reaching higher up the rock.

With the sunlight reflecting directly off the rock, what we see is the change in surface texture of the rock so that areas where the smooth surface of varnish has been removed appear darker. The heart is still visible, but the spiral within it is now very clear, even where 1964 has been inscribed over. New drawings appear lower down, a complex scene which possibly includes two human figures, all but invisible under normal lighting.

Most of the drawings on the southern face of Paria Caca Rock are visible, just, under normal illumination. The same may not be true of the inaccessible face of the rock overhanging the river bank. Certainly the two tupus stand out white from certain angles, whilst the horseshoes and lines of dots appear dark.

The southern face of the rock of the tumis, presents a large surface with a few stand-out images – llamas low down, with a fantastic bird, and more llamas with human figures leading them beneath a ridge of the rock. There are several foxes with great spiral tails, and darker marking can also be made out – a pattern common from textiles, four boxed spirals in a line, on the left. Low down on the right there are two series of twelve parallel lines, like the pinnate leaves of a Schinus molle, the Peruvian pepper tree, which grows along the river, or a ribcage, human or camelid.

In a sloped depression on the rock face, the name JUAN, presumably the author also of the 1964 heart and the JMJR , stands out in bright white, with some other murky markings round about.

But when the slanting sunshine reflects off the surface in early July, the same camera angle reveals dozens of previously unseen images. We have a view into an earlier phase of rock art. There are no foxes and fantastic birds here. There are geometrical patterns of lines, grids, and dots. There are figures which are filled in rather than outlined, squares and triangles. A series of dots marches either side of a white natural vein in the rock, like stitch marks on a wound. There are thickly outlined parallel lines, stylised birds flying upwards. A lobster man with a curved tail reaches three fingered arms upwards. Curving, twisting lines run across the face of the rock or march from top to bottom.

The southern downstream face of the Rock of the Tumis, photographed in August with the sun high in the sky (above) and in July 2018 with the sunlight reflecting directly off the rock face towards the camera (below). A rich array of dark images is revealed on the panel.

The textile design and several llamas are visible in normal sunlight in the top image. Different angles of reflected light reveal many more designs (below and bottom).

Now we can see a clear difference between the newer white designs and these darker shapes that are only revealed by low July sunshine and, perhaps, by moonlight. But we have to be careful about dating these shapes.

My previous estimate was based on the assumption of a thin coating of dark varnish growing at a constant rate on the stones. This is simply not true. We know that only some rock surfaces have that characteristic shiny black appearance. Even the same rock only has the varnish on some surfaces.

Three of these are south facing surfaces, steeply angled, close to the river. Elsewhere, on rocks just a few metres further from the river or a few metres higher, we see the effect only in patches.

We can however see the varnish, and so just walking around the orchard terraces amongst the stones I can get some understanding of where and how it forms.

Under normal illumination JUAN`s graffiti seems to be the only clear marking on this panel, but with reflected light (below) a complete figure appears. The lettering of Juan is just visible down the right hand side of the lower image.

We have already seen that the southern, steep sides faces of the three most southern rocks are deep black, and the designs marked on them vary from bright white to almost neutral, the natural colour of the rock. The rounded northern faces or the flat tops present a more grey appearance, and there is little to differentiate between one inscribed design and another.

Moving through the stones upriver, we find that the same applies to the Rock of the Shaman, the Rock of the Spiral, and The Parrot Gauze Rock. Steeply sloped southern and eastern faces have varnished surfaces, and their is some differentiation in the image brightness, but horizontal or northern faces, and their images, are uniformly grey.

This kidney motif on the Rock of the Llamas is crossed by a dark streak which appears to fall from the top face like dripping moisture. The rock face is made shiny and the kidney image is darkened by the varnish.

On the northern upper face of the Rock of the Serpent, this pattern of dots inside a bottle shape sits aside a darker streak of rock which runs down the face, and a brown, worn area. The design was presumably all done at the same time, but the growth of varnish in the centre of the image leaves the left hand side to the observer) looking brighter. The more recent T-shaped tumi below is whiter, unaffected by the varnish. The half buried Stick Insect Rock (below left) is south facing, almost vertical, and close to the river. Its surface is a rich and shiny black and the images, a pair of stick insect figures and vertical trails, are difficult to make (below right) out except in direct reflected light.

The eastern, river-facing side of the Rock of the Llama Trails is decorated with several vertical snakes or rivers, running down the face and seeming to separate the long rock into distinct panels. Around the foot of the rock is a white border, ten to twenty metres high, from the dusty gravel upwards. It suggests some different weathering process here, perhaps because the ground level was higher, covering the stone. But following the border round I find several places where the dark upper surface extends to the ground. In fact the surface is darker here, and standing back from the rock, it seems smoother also. This is an area of growing rock varnish, changing the surface. At one part, it seems as if it flows from a smooth depression in the upper surface of the rock, like a stream of water.

Here is a clear demonstration of the formation of rock varnish, on a steeply sloped surface, facing south or east, with moisture from rainfall, dew or river spray. The varnish forms over the graven images, reducing their brightness. It also forms over the white band at the foot of the rock, where perhaps it was covered by soil – note that there are no engravings in this band.

There is sufficient evidence, then, that there is varnish formation on the rocks, according to the conditions of the surface and its orientation, and that this varnish changes the appearance of the surface and reduces the brightness of engraved images. If the surface conditions are the same, then we can expect varnish formation to be the same across the surface, such as for the Stick Insect Rock. For larger surfaces, where the inclination changes, we have to be careful. And in any case, we have yet to justify assuming that the rate of varnish formation, for any surface, is constant.

Nevertheless the hypothesis that older images are less bright would appear to have a theoretical basis, for a surface of the same orientation, inclination, and incident moisture. With care, on the southern faces of at least three rocks, this gives us a potential basis for dating the petroglyphs, on a stronger basis than any previous work in Peru has achieved.