I book a private dining room at The Blue Moon, an exquisite Italian restaurant in Lince, an upmarked district of Lima. It is close to one of my favourite outdoor spaces, Parque Ramon Castilla, and a few blocks from Huaca Huallamarca. Every Sunday they offer a buffet which includes an astonishing array of Italian and Peruvian dishes with a special interest in la chasse, wild game. Rare delicacies such as salmon and trout, hare, pheasant, buffalo, venison and porcini mushrooms are roasted, cured, smoked, pickled and potted. Food like this in the streets of Lima is a surreal experience. But I have more surprises for my guests.

Mayra and Amy, Tonkiri and Charley, Canella and Suyana will be joining me for lunch. I am also expecting a special guest from Cajamarca.

Whilst I wait for them to arrive I look around at the extraordinary collection of ornaments and photographs that decorate the restaurant. There are old wine labels mounted and framed, toy cars, medieval pistols, leather riding boots, split cane fishing rods, black and white photographs of Sardinian beaches, rifles, trombones, Homburg hats, movie posters, silver tankards, wicker covered bottles, violins, pottery milkmaids, copper pans.

I could imagine someone from the Andes trying to interpret this. “These cars, what do they mean? And the pistols? Is it some kind of threat? What is this girl with a cow?”

And yet the ambience would be clear enough to most of the restaurant’s regular customers, an evocation of affluent nineteenth century rural Europe, designed to appeal to the nostalgic sensitivities of Lima’s elitists, and indeed to me.

I have taken a similar approach to the stones. “What does this mean? and that? What is a tumi? Why are there all those llamas?”

But now I believe I can see beyond the surface detail and perceive the bigger picture. Like the boots and the bottles, the pistols and the pans, each image in isolation means little. It is how they are combined.

I have promised my guests that I will lay this out before them this afternoon. Whilst I wait, I sit by the bar and try a dark and smoky armagnac, an oaky rural French brandy I have never before seen in Lima.

********************************************************************

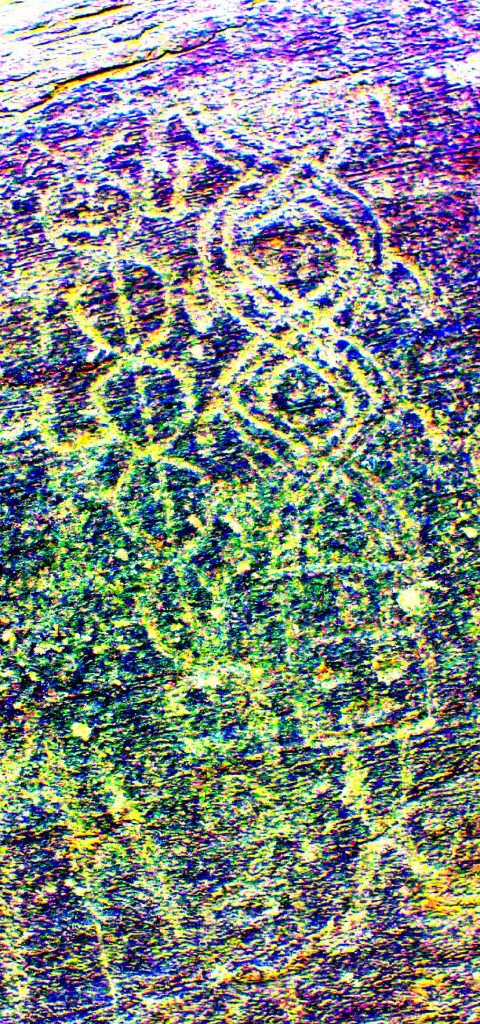

“As you know,” I say, looking round the table, “I have spent three years investigating these petroglyphs on the banks of the Rio Mala. Each one of you has played a part in that.

“Mayra first told me about the Calango stone. And we discovered that there were more stones further up the valley. I was astounded to see these panels that appeared to be saying so much, without anyone listening today.

I am not going to heroically announce what the stones “were for”. “I am not claiming to have “found the answer”, or “solved the problem”. The site is too complex for that. But I have three big ideas to share with you, plus a few loose ends.

“On our first visit we saw two very clearly drawn figures, prominently male, holding to their lips (or noses) long rods or tubes ending in globes.”

I show the images on a screen the restaurant has put up on the back wall.

“With visions of the Yanomami and their snuff taking rituals, I thought of these as pipe-smokers. Visiting Huancor, whilst Mayra was in Venezuela, I found similar figures. One very large panel showed five pipe-smokers. The pipes were longer than the people were tall. There were more figures on the panel that I will call dancers.

“Are you suggesting this is a group of related figures?” asks Charley. “Or have they just been drawn over time, by different people on the same rock panel?”

“I think these Huancor figures on one panel are related. All the figures are drawn with the same A-form legs, and have a similar patina. I believe I can explain what they represent.”

I display a few more images on the screen, showing other pipe-smokers, several figures with dreadlocks, and others with complex headdresses or hairstyles.

Two more “pipe smokers” at Huancor, engraved on a rock a few hundred metres from the previous panel. The original image (left) and a DStretch enhancement (right). The figure at lower left sports dreadlocks. Again, there is a nearby figure with a baton and big hair.

“Then one Saturday afternoon I was sitting on the terrace, and Canella came up for a chat. She looked at these photos and said “I think they are playing trumpets.”

“But these trumpets would be three metres long!” I said.

“That is how they are,” she replied. “The clarins of Cajamarca. I have a friend who makes them.”

It was time to introduce my special guest.

“And I am so pleased to say he is here with us, Julio Nestor Zamora Castro.”

Julio was a short wiry man in a white shirt and jacket, with a shy smile. He stood up.

“I have asked Julio to tell us a little about these giant trumpets,” I say, “because it is his life’s work, his passion. Unlike a Limeño gringo like me, he understands the cultural context.”

Julio looks around the table.

“I was at home in Cajamarca sitting in the back of the instrument shop when I got this email from John, with a photo,” says Julio.““These images are drawn on a stone in Mala and are probably 1000 years old. Interessante no? Que te pienses?” I was delighted but not entirely surprised. For me this instrument is a memory of the ancient Kashamarkinus and their wind instruments such as the Guallay kipa or pututo, the conch shell, and the trumpets of the Moche Culture.

“There are many of these trumpets, from Mexico down to Chile. They have different names, because once all these peoples spoke different languages. But it seems that music and ritual is something they shared.

“The longest trumpets can be six or seven metres long. In the Andes, these instruments are only played by men, at festivals related to the agricultural calendar. In north-eastern Argentina, they play the erke, and the Mapuche in Chile play the trutruca.

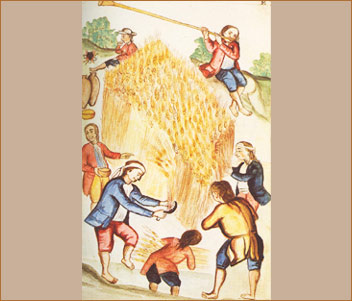

“In 1784 the Bishop of Trujillo, Jaime Martinez de Compañon, visited Cajamarca. He commissioned a series of watercolours of daily life. One shows the clarin being played whilst farmers harvest the corn. But I believe these instruments are much older than that.

Trujillo`s 1784 record of colonial life

“We use the clarin today in Cajamarca and nearby towns to accompany festivals and dances. We have local artists who paint the clarin, poets who celebrate it, even a hymn to the clarin. It is part of our regional identity.

“You have to give the clarin a drink before you play it. Aguardiente or chicha. Some christians in Cajamarca say this is the devil’s work, to make the clarin drunk. But the clarin player, at the end of the fiesta, is usually drunk too.

“The Kashamarkinus had a stable society here for 1500 years before the Inca came. Our pottery is found in the jungle, on the coast, and as far south as Cusco. Maybe our clarins travelled with our pottery.

The Cajamarca clarin being played at an annual festival.

“Sixty years ago, on my Aunt Lucia’s smallholding, I listened to her friends play the clarin, the flauta and the caja, at the end of the day. It means, for me, the hard work and friendship that country people share. Those memories remain in my heart.”

Julio sits down, abruptly, emotional. I hurry on.

“Julio has written a wonderful work about the clarin. CLARIN CAJAMARQUINO SHUKCHA KASHAMARKINU Valor y construcción. Julio Néstor Zamora Castro. Thanks Julio, not just for joining us today, but for everything you have done to appreciate and support your local history and culture.”

There is a polite round of applause.

“Thank you Julio,” says Flor.

“Get the man a drink,” says Charley.

“So, now I am convinced that these pipe-smoker images show trumpet players,” I continue. “And we see two other types of figure with them at Huancor. One holds a staff, and has a plait of hair flying behind him. The other has a flat hat with a square peak, like an upside-down T. This combination of figures is repeated on other panels. Do they refer to some kind of annual ritual that took place at certain times of the year?

“I felt that the answer was yes, but I needed more evidence. I went to see Suraya, and sat in her wonderful back garden in the heart of Lima, full of trees and birds, and told her that I am stuck.

“After I took her to see the stones, Suraya gave me a copy of the Huarochiri Manuscript, with its descriptions of festivals and rituals, history and legends for the people of those highlands. Those tales talks of dances but not of musical instruments or hats and headdresses.

Now she tells me about the Extirpacions….Suraya would you like to continue the story?”

“In the 1980s,” she begins,” I was running a Fair Trade organisation exporting Peruvian handicrafts. And there were so many problems – unstable currency, corruption at the port, poor product quality, unreliable transport. But whenever I felt like giving up, I would pick up Pablo José de Arriaga’s 1621 treatise on La extirpación de la idolatría en el Perú.

“Part of it is a step by step manual on how to carry out the Visits, where a group of Jesuits with absolute power goes to a community and spends three or four days looking for any signs of traditional religion. They then punish anyone involved and destroy any objects they find.

“Their interpretation of traditional religion was a broad one. It included virtually all native rituals, beliefs, music, dance, art, and traditions. In all truth, they aimed to destroy everything the people valued.

“So I would read the Extirpacions for half an hour and rediscover my commitment, feel re-energised. I felt I was undoing the work of the visitadors by giving value to these community handicrafts.”

“And when John asked about these long trumpets,” she adds, “I knew I had read about them. It did not take me long to find the reference.”

“… in their solemn festivals, which are usually three each year,” she reads aloud, “.. . they drink, and sing, and dance, and . . . play other instruments, which they call succhas, and put on some heads of deer, which they call guacu, and of these instruments, and horns they have a very large supply…and everything is burned on the day of the exhibitions.”

“The exhibitions,” she explains, “are when the “Visitor” extracts confessions from idolaters who continue these uncatholic practices. They holds a show in the main square where the idolaters are whipped, or worse. All the pagan items that have been uncovered – including their drums, costumes, and succhas or trumpets – are burned. It might also be relevant, given what John has said about elaborate hair-dos, that cutting of the hair was also a punishment prescribed for these pagan priests.”

“So Arriaga links these succhas or long trumpets to the three annual festivals, which he wants to eradicate,” I add. “Succha means reed, and Julio had told me that the Cajamarca clarins were also called succha. But Suraya found more.”

“Later in the treatise,” she continues, “Arriaga compiles a list of demonic activities which the witch hunters, the extirpadors, should investigate. This is more specific.”

“13 Item,” she reads aloud, “if they know, that when they gather to take in the harvest from the fields, they have a ceremony, with a dance they call the Ayrigua, tying some cobs of maize on a stick or a tree branch, and dancing with them; or another dance they call Ayja, or Quaucu: or with an instrument they call Succha . . .”

“Ayrigua means harvest,” I point out. ” “Arriaga also wrote about their festivals, “. . .The third is when they harvest the corn, which they call Ayrihuamita, because they do the dance of Ayrihua at that time.” Now I have a direct link between people playing these trumpets, dancing with maize cobs tied on a stick, at pre-hispanic harvest festivals on the central coast of Peru. That is what the Huancor panel depicts, and what the trumpet players at Cochineros refer to. An annual festival where people get together, in May at the time of the disappearance of the Pleiades. Forty days later the Pleiades reappears, and there is another festival in honour of Paria Caca, marking the start of the year around June 21st.”

“I’ll buy your theory about the trumpet players,” Charley interrupts, “but what about the dancers with bad hair? You said this was a complete scene.”

“You are right Charley, the pipers at Huancor appear to be part of a complete tableau. The panel shows five trumpeters and another nine figures, two with dreadlocked hair, two with wide-brimmed hats, and four with tall headdresses, and all carrying batons.”

“I have seen something similar at Miculla where there are groups of pipe players, with plaits or dreads, who appear to be dancing,” says Charley.

“Which supports the idea that these images represent an event of music and dance,” I reply. “At Huancor, the panel shows a complete representation of a performance or ritual. At Cochineros there are just the trumpeters, and perhaps baton wielding figures. I am getting closer but a key piece is still missing. So I ask myself who plays these long trumpets today?

“In Santiago de Chocorvos, 2500 metres in the highlands above Huancor, they have an annual Carnival with traditional dances and music. A dozen men play the five metre long huarajo. They move from village to village, with dances and celebrations.

“These modern communities proudly video their annual celebrations and post them on YouTube. Some write blogs online to describe the costumes, the songs, and the music of these ceremonies. In Santiago de Chocorvo, the dance is called Coqueta, The Flirt, and the accompanying song warns the girls “don’t be a flirt, if you make a mistake, it is nobody’s fault but you!” A blogger from the town writes “this is the time to fall in love and chase your partner; if not, you can try again to sing and dance the following year.” There is no doubt that this is an opportunity for people from different villages to come together, and a celebration of fertility.

“Then I find a video online showing ten or twelve men blowing on their long trumpets, parading in a circle. They are joined by dancers, men in white trousers and waistcoats and women in wide skirts who twirl and hop, stamp and bow. A group of women encircle, dancing round the edge and then into the centre. These women wave sticks in the air, and the sticks are decorated with ribbons and balloons.

“As I watch the video another figure joins them, dancing to one side. He wears black trousers, a broad finely woven poncho, and a wooden mask. He is the leader of the dance, the master of ceremonies.

From his head rises a crown of long balloons, waving and swaying as he dances.

“This is a continuation of a pre-hispanic ceremony Alliaga tried to stamp out. Here are men playing their succhas, their long cane trumpets. The women have adorned their sticks with colourful balloons. “A dance they call the Ayrigua, tying some cobs of maize on a stick or a tree branch, ...” is how Arriaga described the harvest festival.

The solitary masked figure represents the master of ceremonies, a priest or huacsa. His dark trousers, his quality clothing, his hidden face set him apart.

Most significant of all, the crown of balloons recalls the long hair or dreadlocks worn by the priests, signifying their otherness. The same dreadlocks shown on the rocks of Huancor and Miculla.

“What do you think Charley?”

“I have seen mummies with braided hair two or three metres long, in museums at Nazca and Trujillo, says Charley. “They are thought to be priests or shamen, certainly not someone who goes out to work in the fields every day. So you think the trumpeter images on the stones of Huancor and Cochineros represent a seasonal festival, 1000 or 2000 years ago? A festival that is still held today, essentially unchanged?”

“Yes. I believe so. It might be that the festivals started here, or passed by here. Festivals that unite different communities tend to be travelling events. But this raised terrace above the river with its hauntingly blue-black stones, would be in a liminal zone. The site is positioned between the coast and the highlands with a trackway connecting the two.

That then is my first proposal, that Cochineros was a site used in part for festivals which helped bring disparate communities together. And that many of the motifs marked on the rock may reference these events.

But of course the trumpeters represent just a tiny proportion of all the images on the stones. And although we know that these festivals existed before the spanish invasion, they do not give us a date.

“How old are these images? That was a question I wanted to answer. I was struck on my first visit with Mayra by the variation in the brightness of the images. I thought I could use this to put them in chronological order. The brightest images being the most recent and the darkest the oldest.

“I found one panel included modern graffiti with a date. The next brightest images on that panel, I surmised, were close to the Spanish arrival – the last ritual drawings made on the stones before the extirpaciones and reducciones destroyed the local society.

“That gave me two fixed dates. Now I could calculate a date for each image depending on their brightness. And I found that the oldest, darkest images go back nearly two thousand years.

“Hang on there,” Charley interrupts. “How are you measuring this brightness?”

“At first I just took pictures with a digital camera, and analysed the images using a freeware called Image-J. I had two images taken at different angles on the same day, and they gave consistent results.”

“But digital cameras compress the image in several ways,” Charley says, “and surely what you see depends on the brightness of the sun?”

“To be honest Charley, I was surprised it was so simple. I bought a better camera and went back a year later. I took RAW, uncompressed images, from different angles and on different days. As long as I avoided direct reflection from the sun, I got consistent results. It helps that I was studying a more or less flat panel, that is getting uniform illumination.”

“Let’s accept, for now, that the results are consistent,” says Charley. “It is still a giant leap to say that the brightness you measure correlates with age.”

“Maybe it looks like a giant leap,” I reply, “but actually it was several years of tiny steps, and going back and double checking those steps. I am presenting conclusions here. And on this particular panel, on the images I chose to measure, I believe it is robust. I tried and failed to extend it to other images on other panels. But I can show you the raw data later and you can check it for yourself.”

“Take a look at this image, for example, ” I say to Charley, showing a swift or swallow like figure from the right hand side of the panel. “It is well formed with clear edges and filled interiors. That is unusual – most of the images are formed with simple lines. But there are a six figures on this panel, drawn in the same manner and with the same care. They include two swallows flying upwards on one side, and three lake-like anthropomorphs reaching up to the peak of the rock. Style alone suggests they are related. They all have a similar brightness, dating to 800-1100 BP, according to my measurements.

“This is approximately when the people of the Huarochiri Manuscript took control in the highlands, and swept down to the coast, by their own account.

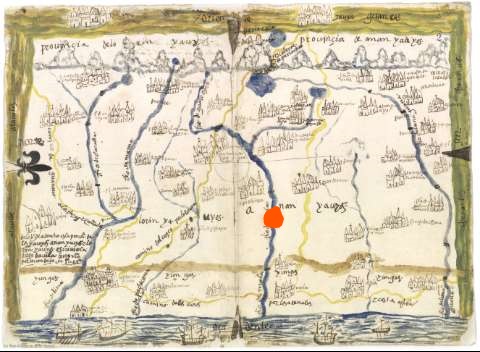

“This group of figures appears to be imagining the rock as a mountain. It is remarkably similar to a map of the region made for Diego Dávila Briceño, the first spanish corregidor of Huaro Chiri, in 1586.

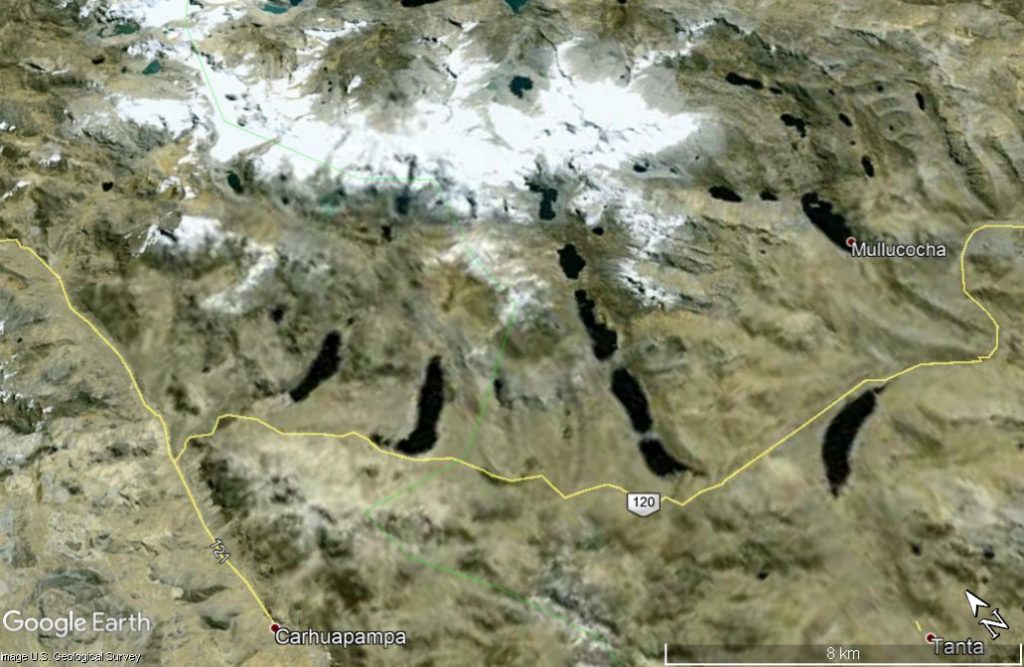

“The map is largely geographical but it also represents the mythology of the region, as we can see by comparing with a Google Earth image of the area.

“It shows the sea as a strip of blue at the foot of the map, in opposition to the mountains as a line of sharp white peaks at the top. A brown line parallel to the coast represents the limit of yunga, or coastal lands, and Calango and Coaillo sit on the border.

“The left hand side is Lurin, and the right is Hanan, the duality which all Andean communities are thought to have had, certainly all Inca towns. Cochineros is positioned on the central river of three major rivers, which flow all year round, and flanked by two minor, frequently dry rivers. It is neither on the coast or in the highlands.

” The most interesting feature of the map is at the top centre, where there is a double peak marked “paria caca idolo yaro” and a stair winding round it labelled “escalera paria caca”. The map was made by someone with local knowledge and it was still acceptable to identify the position of “idols”. The extirpaciones were 22 years in the future, in 1586.

Below Paria Caca, by the stairs, a large lake is marked on the map. Geographically this is a small lake, Mullococha, but in mythological terms, it played an important role. It was here that the battle between Paria Caca and his predecessor was fought. The lake itself was created during the battle and played a decisive role in the defeat of the cannibal god Huallallo Caruincho.

“So I suggest that the fringe of white lines on the peak of this panel represents the snows of Paria Caca and neighbouring peaks. The rounded bodies with their curved tails and upreaching arms could be lake deities – the lakes visible on the Google Earth image have a similar shape. The lines of dots at the foot of the panel could represent coastal roads or the border with the yungas.

“And then there is the line of dots rising up the panel, but ending before the peak. This could represent a path to the Paria Caca shrine. The bottom of this line is old and faded, but higher up it appears to have been re-engraved more recently. Around the same time, two figures were added by the path, the lower one possibly carrying a llama, the upper one sacrificing a llama.

“These figures and re-marking of the path seem to have occurred around 1585 CE, which suggests the panel retained its significance for up to six hundred years, and sometime after the Inca reached the coast, the Paria Caca cult was revitalised.

” In general terms, I feel this rock was seen to represent Paria Caca. It is in fact a twin peaked rock, when viewed from the opposite bank of the river. The swallows and lake deities were drawn with such care, around the time when the Huarochiri people, according to the manuscript, swept down from the highlands towards the coast.

“But there were figures on the rock before, and more figures were added after. This Paria Caca representation is just one phase of its history.

“At one relatively recent stage, around 500 years ago, a wave of crude new images swept over all the boulders on the site. A few motifs were repeated without great care – 40 tumis, 50 images of llamas, scrawled on 8 rocks. But they were inscribed with respect. They were not drawn on top of existing images. They were placed in the spaces, or on the less used north facing panels.

“And then nothing, until some modern graffiti, names and initials, and one prominent date. Those were done without any respect or care for what was beneath.

“But the more interesting images are darker and older. I had spent many hours studying the stones and taking photographs before I noticed them.

“I was leaving the site in late afternoon, walking down a steep and narrow path towards the river. It was a few weeks after the solstice. Looking back, I saw the sun glancing off the face of a long broad panel, sloping steeply north to south. I was astonished by what I saw.

“The panel was lit up by the reflected sunlight, and it came to life, with dozens of finely drawn images that I had never seen before.

“It was a lucky chance. With the bright sun reflecting off the rocks for most of the year, these images are all but invisible. Only for a few weeks either side of the solstice can they be seen clearly from the ground.

I look out across the table.

“I have a few more points,” I say, ” but I can see you are hungry. So let us enjoy the buffet and I will finish off after lunch.”

*******************************************************

“So, welcome back,” I say to the group that is now replete with smoked trout, jugged hare and strawberry cheesecake. “With apologies to Charley, I am going to quickly summarise my ideas. For those who want a more rigorous argument, I have written that here.”

I have a pile of photocopied notes in front of me that includes graphs, references, photographs and maps.

“So, I have suggested that the trumpet players imply a seasonal festival of music and dance. The depiction on the Huancor stones includes other participants in the ceremony, identified by their hair or headdress. Events such as the Santiago de Conchorvo Carnival recall these old festivals.

“I have dated some of the drawings by measuring the brightness of the engravings,” I continue. “One group of images, which appears to relate to the rock as a mythical mountain, dates from 1000 CE, plus or minus 100 years, to around 1500 CE. But the oldest images, only visible when the sun glances off the rock face, may date to between 300 BCE and 300 CE.

“All that is a little too diagnostic. For me, the broader picture is this.

“Firstly, for 1500 years, these rocks, these terraces by the river, were a sacred place. And though allegiances changed,we can see from the patinas and layers of engravings that the people who came here respected the previous users, they drew around their motifs rather than over them, they shared the space. They shared ideas, I believe. This was a place of communication.

“Secondly, these drawings were not casually done. There are four stones at Cochineros with around 150 engraved motifs each, and another five with twenty or more. There are two thousand images over 1500 years. So on average, only one or two drawings were made each year, across all the stones.

“I have suggested that one, prominent, upstanding stone, that resembles a mountain with twin peaks, was seen as representing Paria Caca.

“Looking over the shoulder of that rock, on a clear day, I have seen far away clouds at the head of the valley, which seemed like snow capped peaks.

“But what of the other giant boulders?

“Societies in the central Andes saw themselves as partnerships between pastoral, mountain people, and mid valley farmers. I use the past tense, because this is what archaeologists tell us. But these deep concepts still hold true.

“The valleys were warm, fertile, and female, and the male mountain heights provided the waters. The male heights were invaders and the female valleys were deep-seated, unmoving.

“Towards the south of the site is this prominent rock representing the male deity Paria Caca. At the northern end is a long low stone, some twelve metres long, with a flat top more or less level with the ground, and a two metre vertical face towards the river. It is as deep-seated as it can be.

“There are twelve serpentine trails marked down the vertical face, streams of water. There is a natural channel on the top of the rock, leading towards the vertical face, decorated with nine tupus pointing down. Tupus of course were worn by women, buried with women. On the vertical face there is a dark patina which suggests that at times, perhaps at seasonal harvest festivals, water was diverted over the rock to flow through this channel. The symbolism of fertility continues with engravings of multiple concentric circles and swelling tubers. This then, for me, is a dedication to Chaupi Ñamca, the mother figure, the sister/wife of Paria Caca.

Tupus pointing down the channel across the upper surface of the rock (above left), and the darkening that could be caused by a flow of water at annual festivals (above right).

“But this is not about engravings on rocks, the bigger picture is festivals. As represented by the trumpeters.

“In Huarochiri there were two great festivals for Paria Caca and Chaupi Ñamca. They were held in April and June, separated by the forty days when the Pleiades disappeared from view.

“Charley told me over lunch that the visitadors wrote explicitly of two such festivals, separated by forty days. The first, in April, was for Pariaqaqa, and the second for Chaupiamoc. But this was 200 km to the south, in Cajatambo.

“So these were not just local cults.

“And when I visited with Mayra and Amy just a few weeks ago, there on the rocks we found a Gnomon to predict the festival dates.

“I found the gnomon!” Amy shouts with glee.

“What’s a gnomon?” says half the room.

“Amy, can you tell us?” I ask.

” A gnomon is a device to see the seasons or the time of year from the shadow cast by the sun!” she replies. “Yay!”

“Exactly, ” I continue. “Amy found a design marked on the stones, under the shadow of an outcrop of rock, that can be used to accurately predict the dates of these two key festivals.”

“The Yanca, the ritual manager, would announce the date, using “his solar observatory”, the gnomon marked on the stones, according to the Huarochiri Manuscript. So what is he doing, this Yanca? He is organising an event that brings people together.

“The stones, whether at Huancor or Cochineros, were not necessarily the site of the festival. The stones had a bigger purpose than that. There may have been rituals there, but the people would move from place to place, as they do today. The festivals link communities.

“The stones are located in the centre of the historic region of Yauyos. They lie between Hanan and Lurin, the upper and lower sectors, and between the coast and the mountains,” I say. “A road goes up and down the valley, and ancient paths go over the hills to the north and the south. I can’t ascribe particular meaning to each of the engravings on the stones, over 1500 years, but it is clear that they demonstrate continuity, a sharing of ideas and mutual respect. And that, I believe, is the message they have for modern Peru.”

“Suraya told me about La Candelaria, in Puno. What the tourists see is thousands of people dancing in colourful costumes, and getting drop down drunk. But you can go to Campo de Martes in Lima on a Sunday afternoon and these people are in training, learning the dances. They start practising in August for the February festival.

“Candelaria is not a festival for the people of Puno,” adds Suraya, “it is not a diversion, it is an obligation. It is a time for the people to talk to their gods, to thank them for the past year, and to submit their requests for the year to come. They are negotiating an annual contract between the planet and human beings, and nothing could be more important than that.”

“And that reminds me of the words of a Huichol man I met in Mexico,” I say. “He walks five hundred kilometres every year to visit his historic homelands and consume peyote. “It is not easy for us”, he told me, “non-Huichols have no idea how hard we work. We are ensuring that not only Huichol corn will grow, but your corn and other food as well. We Huichols were born to be the caretakers. The deals we strike with the gods are for the benefit of all, which is why we work so hard at it. If we stop, then many on earth will go hungry.”

“A hundred thousand dancers take part in Candelaria,” I continue. “Some speak Aymara, others speak Quechua. They come from Peru and from Bolivia. This event bonds a society.

“Canella told me about the festival of Quoyllur R’iti, a pilgrimage to a mountain near Cusco, to watch the first rising of the Pleiades. Again, there are thousands of participants, from the north-east and the south-west, Quechua and Aymara, farmers and herders.

“These rituals bring people together.

“Life in the Andes is hard,” says Suraya. “The weather can destroy your crop in a day. People want to spread the risk. When a crisis hits, they need friends. Not in their own village, but from lower down the mountain or further south, where the floods or the frost may have passed over. A broad based society is a form of insurance.”

“Archaeologists talk of vertical archipelagos” adds Charley, “or zonal complementarity. “Highland communities maintained links with people in the valleys, and vice versa. It was a way of sharing resources. Camelids for meat and fibre in the altiplano, potatoes on the high mountain slopes, maize, beans and peppers in the upper valleys, coca in the mid-valley, fruits and tropical vegetables on the coast. We can see it in the seeds and plants we find in excavations.”

“It still happens,” says Suraya. “I told John of a llama caravan I joined to trade salt. We journeyed for five days, a hundred kilometres, and at each town we passed through, the llanero had a cousin or an aunt.”

“These networks were not market driven,” explains Charley, “they were based on kinship and labour. People living in a community could farm the land, and if you help your cousin harvest his potatoes, you get a share of the crop. Later, because these ecological niches have different seasons, your cousin’s wife will help you gather in the maize, and she will take a share.”

“We play football,” says Tonkiri. “The World Cup”.

It is the first time he has spoken, and everybody turns to listen.

“We call it the little World Cup, the Mundialito, but it is an annual football competition for the peoples of the forest. The Shipibo, the Yanesha, the Ashaninka, people will travel for three, five days by canoe to reach Pucallpa. Others return home from Lima.”

“And . . . you play football?” asks Amy, incredulous.

“We play football. Mostly barefoot. The competition is fierce. But it is the only time of the year that all my people and others come together, across great distances. So we do many other things. The elders, I expect they discuss the loggers, the illegal goldminers, climate change, and the price of coffee. For myself, I make new friends, maybe meet some girls. I believe that in the past, we had a great feast once a year. Now we play football,” he grinned. “And we also eat and drink, sing and dance.”

“We have a Carneval in Venezuela,” chips in Mayra, “but it is not in the European style. The biggest festivities are in a small town in the east, El Callao. This was a mining community with lots of immigrants from the Caribbean and slaves from Africa. They even play Calipso music. Nowadays people from all over the country head for El Callao in February, so this too is bringing people together. Of course we dance!”

“For the spanish and the catholic church, community values and moral values threatened their control, their domination,” adds Mayra, “but they have not been able to destroy these values. Weaken them, yes, but not destroy them. Not even in five hundred years. Outside Lima, there are still communities and they have values which they pass on from generation to generation. There are still people in Peru who come together to sing and dance, and look at the stars.”