“I am hoping you can help me to understand the drawings on these stones,” I say to Suyana, as we sit in the riverside restaurant of La Capilla eating fried river prawns.

From the terrace we can look over the balcony at the river below. It is late August, the waters are low, and small fish are idling in the gentle currents of the clear green waters.

“And particularly, the dozens of llamas or camelids that are drawn on the rocks.”

I feel I have followed the tumis and tupus as far as I can for now. But there are other repeated images on the stones such as the llamas. At least that is what I call them.

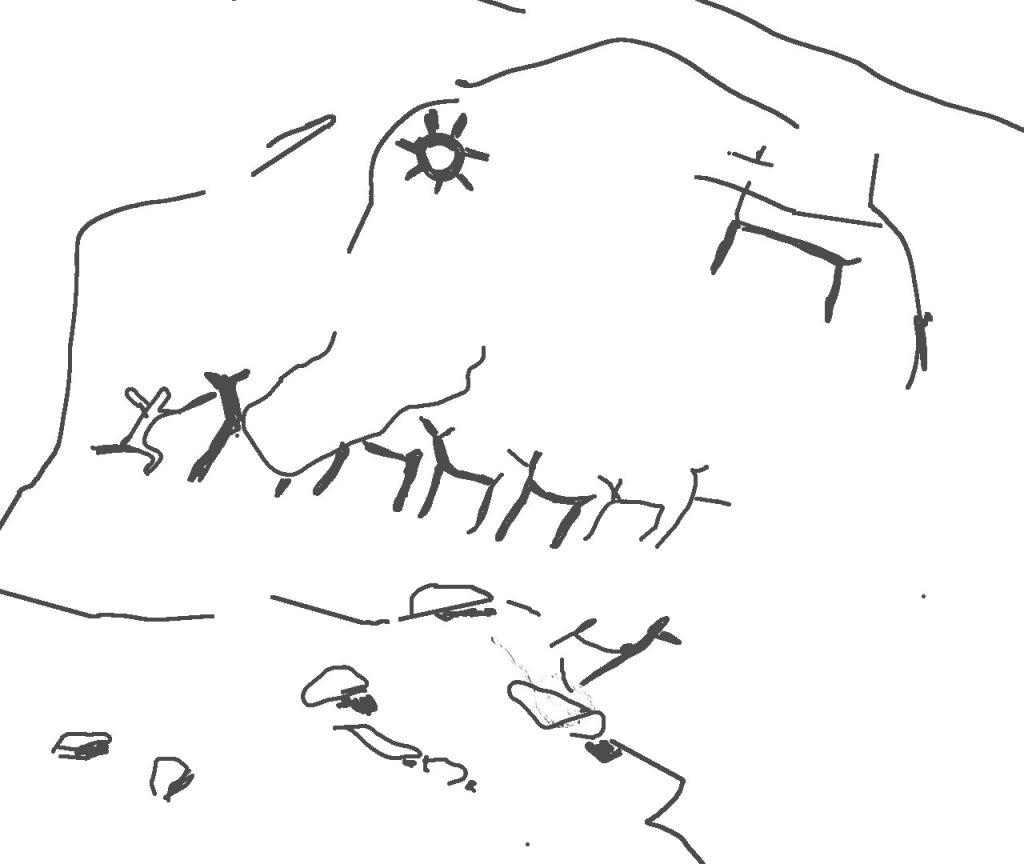

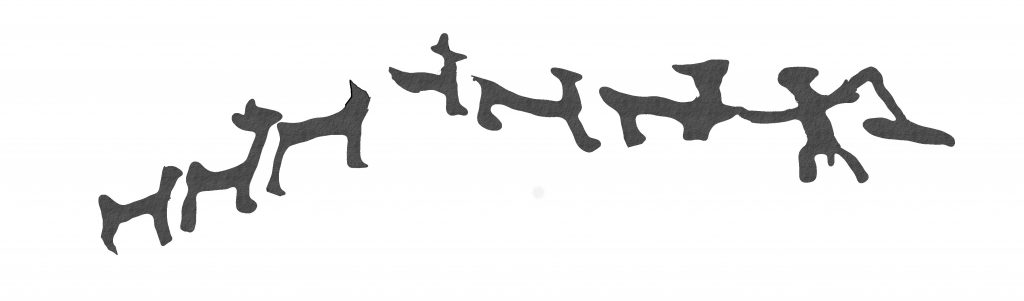

There are almost 100 of them, and most are drawn in profile, with simple lines. Two vertical lines for legs, a horizontal back, a neck and a tail, head, ears and nose. But a dozen are drawn more freely, with four legs, as if in motion. Were they the same animal drawn in different styles? Or did they symbolise different concepts?

There is little doubt that the images represent camelids, animals unique to South America. But there are four different animals in South America. The domesticated alpaca and llama are herded in the highlands and bred for their fibre and meat. The vicuña and the guanaco, their wild ancestors, maintain a fragile existence in reserves and the more remote regions of Peru, Chile and Argentina. And I can hardly tell them apart.

Suyana is a slim fit seventy year old who founded and ran one of the world’s first Fair Trade handicrafts companies. She has travelled the length and breadth of Peru seeking out artisan crafts in remote areas – ceramics from the Amazon basin, natural perfumes from Cuzco, weaving from islands in Lake Titicaca.

“I was brought up in Juliaca” she tells me. “It is the market town for the region of Puno – really Juliaca is one vast market – and Puno has half of Peru’s alpaca, half the world’s alpaca.”

“So did your family keep alpaca and llamas?”

She laughs.

“No, we were the 5% that did not have to work. I did not know such people as the llama herders existed. Better to say, of course I saw them walking in the street or selling in the market, but we did not feel they had anything of value to us. It was as if we lived in the same town, yet on different planets.”

“But you have spent your life trying to create an international market for alpaca knitwear, engraved gourds, traditional embroidery…”

“Yes. Do you remember the stone carving I have on the desk in Lima?”

It was a heavy black stone, the size of a human head. I remembered it well. One side had been intricately carved into the centre piece of the national flag – a molle tree, a llama and a cornucopia overflowing with plentiful gold and copper. And then polished to a fine shine.

“It must have taken a long time to carve.”

Yes, but my uncle had plenty of time. He was in prison. On the island of San Lorenzo, off the coast of Lima.”

“What for?”

“Because they thought he was a member of APRA, the political party. American Popular Revolutionary Alliance. The party was banned for six years. All my uncles were imprisoned, or they went into hiding. So you see in Peruvian terms, I have always been some kind of dangerous revolutionary.”

“But APRA, the party of Alan Garcia, hyperinflation, the overpriced and incomplete construction projects, the prison massacres. . . ?”

“That is how it is.”

As we dissect and dismember our river prawns on the balcony we have a fine view across the river to the opposite hillside. We can see a trail rising up from the valley floor, crossing the incline, and continuing towards what seems an impassable rock face. This is the ancient trackway that threads up the valley, contouring steep hillsides, rising and falling.

“I am thinking,” I tell Suyana, “that groups of llamas would have walked that way, heading upriver, passing by the stones. There are drawings of individual llamas, groups of llamas, some led by a human figure. It was obviously an important theme. But what do these images mean? I hope that you can help me work it out.”

Leaving the restaurant we cross a steel girder bridge across the river. The road bends left and by the roadside is a tall pile of stones topped by a crucifix.

“This was probably a sacred site,” says Suyana,”they have erected the crucifix as a sign of domination.”

“I read that they broke down 37 sites of worship around Calango, and erected 37 crucifixes.”

“That strangely smooth rock that we passed in the car, La Capilla, could have been another. It is very popular with modern Lima catholics.”

The roadside shrine, which we can see across the river, is a yellow rock face like melting wax, on which have been painted images of Peru’s three saints. People pray and light candles in front of the images, then head to one of the riverside restaurants. On festival days there are stalls selling miniature grottos of painted plaster, medallions and postcards.

“Those three saints,” says Suyana, “were an ascetic hermit who cared for the poor, an infirmary nurse, and a doorkeeper at the priory. It is interesting that those who humbly serve, they make into saints, and those who wish to dominate and display power they make into Cardinals and Archbishops.”

“I saw their skulls in Santo Domingo,” I say. The saints, that is, not the Cardinals. One of the most beautiful of Lima’s churches, just behind the main square, not only has these relics but a network of underground tunnels and chambers housing the bones of thousands who were buried in crypts.

“In the sierra there are still skulls in caves where the people go to offer coca leaves and ask for guidance. I enjoy the symmetry between the native Peruvians preserving their ancestors as mummified bodies, talking to them, feeding them, and taking them out for festivals, and the church in Lima displaying those skulls,” says Suyana. “It makes me wonder whether the catholics have eradicated indigenous religious beliefs, as they have tried so hard to do for centuries, or the indigenous gods have taken over the church.”

To the right of the road we take a small path which crosses over a canal of fast-running water, and we are at the foot of the trail as it climbs up the hill. It is broader than it seems from across the river. There are signs of edging stones and steps. A newly built house of poorly laid bricks is based on part of the trackway.

” I expect the road crossed the river here,” says Suyana. “It is very narrow with high banks – the perfect place to build a rope bridge.”

“And could such a bridge carry a llama caravan?”

“Certainly. The spanish wrote of galloping their horses across them. There are still bridges in the sierra in daily use. Every two or three years, the communities come together to weave thick ropes out of tough highland grasses, and replace the old bridge.”

“Something similar would have happened with the roads. An old man in Nieve-Nieve told me the hillside track up the Lurin valley was in regular use into the twentieth century. But it has not been maintained.”

“Quite the opposite, people are building on top of it. And here, they are planting in a burial ground.”

Suyana points to the other side of the path.

A new vineyard is being planted and we can see bones, gourds, pieces of cloth and broken ceramics scattered amongst the vines. This is not the wholesale destruction of grave robbers, just the remnants unearthed by a farmer as he digs a hole to seat his vines.

We walk through the vineyard towards the hillside and come to an open area with some low boulders.

One is marked with five or six small round depressions – cupules. At first I think they could be a natural feature of the rock, but as we explore the area we find more. Then I see a large rock with five parallel lines of dots across the surface, unmistakeably man-made. A little further is a small rectangular enclosure housing a pig. Its stone walls abut giant boulders at the corners, one of which, head high, has a cluster of cupules on its shoulder.

“They say cupules are one of the oldest forms of art. They are also very difficult to date.”

“Would they not be linked to the road?” says Suyana.

“That’s a common mistake in dating rock art. Here we have burials, an old trackway, a spanish crucifix, a piggery, and a riverside restaurant serving camarones. Which of those might be the same age as the cupules?”

“I see what you mean. So how else can you date them?”

“Iconography is one option. The same symbols are seen on ceramics or textiles which are independently datable. Or images of horses, weapons,..”

“Or llamas. There are not many llamas round here today. ”

“Exactly. But some direct method is better – dating the wear on the stones. It is very difficult. Plenty of rock art researchers have made and then destroyed their reputations with dating methods that ultimately proved unreliable.”

We continue to walk amongst the stones carelessly until we find ourselves back near the road, but facing the back of a house. A young man walks out into his garden of peppers and maize and spots us.

“How did you get here?” he asks us, polite but puzzled.

“We came on the path from the old road. Can we get out here?” I say innocently, realising we have been walking across his land.

” Of course. Come this way,” he says, and he leads us through the house. “Would you like a glass of water?”

“If we were in Lima we would have been shot!” I comment to Suyana as we exit the front door.

“Ama suwa, ama llulla, ama qella — don’t steal, don’t lie, don’t be lazy, has been a saying since long before the Inca,” nods Suyana, “but it is in Quechua, so the spanish never learnt it.”

“Lima and the rest of the Peru are two different worlds,” she adds, as we thank the man and head up the road.

***************************************************************

The modern road from La Capilla heads up the eastern side of the valley, and within a few hundred metres the few scattered houses are left behind. To the left of the road is a raised canal with fast flowing water, and beyond this farmland slopes gently to the river. Most of the land is dedicated to fruit trees, and there are hives of bees dotted amongst the orchards. To the right are dry and rocky hillsides, occasionally cut by quebradas, dry valleys.

The trackway, I tell Suyana, was part of the Inca road system or Qhapaq Ñan, a road network stretching 5000 kilometres from present day Colombia to Chile and Argentina. A main highway along the Sierra, the highlands, was paralleled by another along the coast of Peru down to Chile, with interconnecting routes down the valleys. The network was said to total 40,000 kilometres of roadway, through coastal deserts, over ravines on rope bridges, up stone stairways over mountain passes at a breathless 5000 metres, across marshes on pontoons, and through humid tropical forests.

“Have you visited Caral?” she asks.

I nodded. This spectacular complex of stepped pyramids and plazas a few hours north of Lima was thought to be the centre of the oldest civilisation in the Americas, flourishing three thousand years before the Maya built Chichen Itza.

“Nearly five thousand years ago, Caral traded not only with coastal fishermen a day’s journey away but also high into the Andes. There is a four thousand year old temple at Ventarron, further north, where ceremonial offerings including a parrot and a monkey were found. They must have come from the humid forest on the eastern slopes of the Andes, 200 kilometres over high mountain passes. More than three thousand years ago the Chavin de Huantar culture built a ritual centre in a remote valley of the Cordillera Blanca, perhaps because it straddled a key route from the coast to the jungle. The people there ate clams and shellfish from the Pacific, and imported obsidian from 500 km to the south.”

“So you are saying that the people of Caral, of Chavin, also had roads?”

“The tourist guides tell how the Incas built one of the wonders of the ancient world here. A network of roads that stretches the length of the Inca empire at its height. And it is a wonder. But it is not Inca.”

“So who do you suggest built the Quapac Ñan?”

“The Incas brought skilled labour together and moved it around their empire, whether for stonework, irrigation, metalwork, weaving, or road-building. Their talent was managerial, they made things happen, but they did not invent these arts and crafts. The most creative thing they did was to write their own history.”

“Of course this track up the valley was used to transport goods carried by llamas, from the coast to the highlands and vice versa,” she continued, “and goods have been moved this way in Peru for thousands of years. The roads are as old as trade.”

The llama trail as it leaves La Capilla is visible on the far side of the river, climbing from the modern bridge, crossing the rocky face of the mountain as a thin line before dropping towards the river again. It appears intermittently, at times clearly visible with foundations of layered stones, then disappearing as it reaches impossible cliffs, or perhaps climbing higher and away from the river to cut across the mountains where the river bends.

“I have walked such trails with llamas many times,” says Suyana. “This is not the ancient past, you realise, some people still use llama caravans today. There is no other way to get their products to market, without roads.”

“So where did you travel to? What was it like?”

“In the 1980s, I spent a lot of time visiting communities in the sierra. We were developing a range of products to export, alpaca knitwear, weaving, embroidery. But terrorists controlled much of the country. Through fear. The rural people lived between two fronts.”

Suyana was a great storyteller. And she had great stories to tell. I had learnt that it was best to let her continue uninterrupted.

“One night the Sendero Luminoso come and paint a hammer and sickle on the walls. No-one sees them, but the symbols are there in the morning. “

“Some days later the military, the army boys, return and see the graffiti. They gather everyone in the centre of the village. They shout at the villagers. In spanish of course. Few people understand. They drag some people forward, throw them to the ground and shoot them. To punish them for collaborating with terrorists.”

“A week later the guerrillas come back. Now in the middle of the day, and in force. They walk through the village, house to house. They have guns, they break down doors. Everyone is taken into the open space of the village. Mothers carrying their babies. They make speeches and shout. They also speak spanish. And then they take the mayor, a few more, and they make them kneel. Marching around they talk about the glorious revolution and the new world they are creating. And how the village must be punished for giving food to the army. Then they level their guns and shoot.”

“This is our new normal. Travelling on the roads is too dangerous. There are roadblocks. The terroristas and the army boys, they are both stopping the buses, searching people, sometimes shooting people. Or taking them away, never to be seen again.”

“Many people leave the villages and go to live in caves, or rough shelters far from the roads. But to eat, the people still need to get to market from time to time. Putting your goods on the back of a llama and following the old roads is safer. After all, the army and the terrorists are both outsiders. They do not know these ancient trackways.”

It was pleasant striding side by side up this dusty road under the strong sun. We had been walking for an hour and just one farmer on a motorbike had passed us. The apple blossom was sweet.

“Is there anything you can tell me about these trips, that could help me understand how these roads might have been used?”

“I remember a trip I made with a llama caravan through Cotahuasi, near Arequipa. It felt like a ritual journey.”

“The family I was staying with were alpaca herders. But between Sendero Luminoso and the army, it was very difficult to get their wool to the middlemen. So they told me they would travel south to buy salt, and then take it north to exchange for food. It would take two weeks. So of course I said I would come with them.”

“Before the journey begins, we gather in the early morning, in a small corral. The men talk to the llamas, calling them by name. They give them chicha beer to drink. They take the leading llamas aside and make marks in the earth with a stick. They explain to them the route we will take, the climbs and the rest stops. It is a team briefing.”

“Is it true that every animal has an individual name?” I ask.

“It would not be polite to count their animals. “It would be like counting the stars,” they say, “or our children.” They talk to them, call them by name, dress them for festivals, and even hold marriage ceremonies.”

“The relationship between a family and their llamas is very close. They rear the crias from the day they are born. They will give a young child their own llama shortly after the first hair cutting. “This is your llama, you will care for her.”

“Some llamas are chosen to lead the group downhill, and others uphill. Some work best in the middle of the caravan, and others at the front or rear. The men leading the caravan know the llamas personally. They usually divide the llama caravan into teams of twelve llamas. “

This was interesting. “There are drawings on the rocks of groups of llamas, three, six, eight llamas with a human figure. I was wondering what that might mean?”

“Llamas are social animals, and they move in groups with a dominant male, youngsters and females. Typically in groups of twelve. The dominant male will drive away younger males once they threaten his power. And one day, the old male in his turn will be driven away by a younger competitor. Twelve animals is a stable group.”

“I remember a campesino in Cajamarca explaining this to me,” I replied. “I had been watching two or three alpacas chasing another alpaca away. He kept returning, and they continued to spit and threaten him. And then a dog started barking, and the alpacas turned on the dog.”

“They defend themselves as a group, they kill foxes, trample them to death. If you threaten a llama or alpaca, you are taking on the whole team.”

“So why would they be drawing a man with three or six llamas on the rocks?”

“Those are not pack llamas. A caravan has twelve animals, and a lead llama that finds the best path. The people walk at the back, behind the caravan. These drawings show people rearing llamas, not carrying loads,” she says with finality.

The caravan, she explained, travelled 15 to 20 km a day, walking for four or five hours. They carried 25–40 kg loads. The llamas did not eat at night, so each day they had to reach a grazing area in the afternoon. Corrals were nearly always available before and after steep sections, when loads needed to be re-fastened.

“So this road up the valley should connect a series of corrals and grazing areas?”

“I expect so.”

*************************************************************************

The sun is strong now in the afternoon as we walk up the valley, and a wind blows down towards the coast. We cross a quebrada and there are ruined buildings on its slopes, and scattered bones too.

“There are six ruined towns or villages above La Capilla, over a distance of 25 kilometres,” I tell Suyana, “but none of them have been studied in detail.”

“From the fragments of ceramics found on the surface, they are presumed to be from the Late Intermediate period, 1000 to 1476 AD, with some later Inca modifications. The Ychsma controlled Pacha Camac and three coastal valleys close to Lima at that time. But they are are thought to have had little influence here. This valley may have had closer links with the Huarco, to the south in Cañete. A third suggestion is that it had its own valley culture, with its own ceramics, centred around a ritual centre at Checas, 20 km upriver from La Capilla. The truth is, the picture is confused.”

“Which makes the petroglyphs, and whatever story they have to tell, all the more interesting?”

“Exactly. Are there images here that I can identify as Ychsma, or Huarco? Or something else entirely?”

The valley narrows sharply and there is bridge across the river here, with a locked gate. It is access to a private estate. We can see the trail descending on the far side, and with the bend in the river, we are actually looking along the line of the trackway. The hillside is steep but the track seems solid enough, flat and broad, built up on a layered bed of stones.

Turning to look upriver we can also see, behind the cultivated fields, some line of walls on the stony valley rim.

“That looks like corrals to me,” I say, pointing across the river.

“This would be the right distance from the coast, 25 kilometres, a hard day’s journey. It would be a good place to stop, feed the llamas and settle down for the night. And in those fields by the river they would be able to graze the animals or buy fodder.”

We walk on up the valley and pass through a broad area of orchards to left and right. The sunlight reflects from the rippling channels of water between the trees. The valley is growing narrower now, and the trackway across the river tiptoes cautiously across ledges at the foot of towering cliffs. Then the river swings round and the road on our side is tight against the hillside, and as the river narrows we reach the oroya crossing. These hanging baskets that could be hauled across by ropes, like the bridges of grass fibre, were widely used in pre-invasion times.

“Given the number of ancient settlements that we have passed, on both sides of the river,” I comment, “I wonder if there were many such crossings eight hundred years ago.”

“It’s possible,” Suyana nods.

“They may even have been in the same places – Calango, here where the river narrows, and again at Cochineros.”

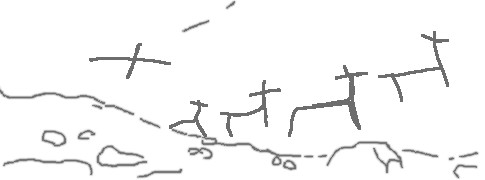

By the roadside is the glossy rock with markings I had noticed on my first walk up the valley with Mayra. But now I can see that the T-markings are tumis like those upriver, and the rock is the same smooth worn blue-black stone.

In half an hour we reach the metal bridge and pause where the road cuts through the old village midden. The strata of human debris are still visible. A piece of fine leather protrudes from the earth and another fragment lies in the road. They appear to be the remains of a pouch, woven together with leather thong. The hide, five hundred years old or more, is still soft and flexible.

“That looks, and feels, like deerskin,” says Suyana. “Look at how the pores are distributed. These are in groups of four. Sheep and lamb have the hair pores in rows, whilst goat pores are grouped in crescents.”

A little further on we find the two cyst tombs that I had seen with Mayra. They have collapsed a little further into the road. I can see now from the bones protruding through the earth that these small tombs of un-mortared square stone walls contain multiple burials – one or two adults in each, and a small baby. There is also an animal skull.

It has wide eye sockets placed either side of the head, a long nose, and is the length of a hand’s span. “That is a llama” says Suyana.

She picks it up and looks at it carefully, turning it in her hands.

“It is a young male, perhaps two years old.”

“How can you tell?”

“Look closely at the teeth. There are just four molars. One set has still to come through. In addition, there are no incisors at the front, though they could have fallen out. But the clearest sign is here. Look at this.”

She points at some small sharp teeth, two either side, that are just peeking out of the jaw.

“Those are their fighting teeth. The adult males will fight for position, and these teeth come through between two and three years old.”

“From a breeding point of view, you do not need too many males. So it makes sense to kill some of them off. They found a lot of mummified llamas, a thousand years old, buried as offerings, down near the border with Chile, at El Yaral. They were also two year old males. And the same pattern was seen with llamas buried with children near the Chimu site of Chan Chan.”

We walk off the road and explore the ruins. There is a whole village here, of collapsed walls, so that we feel we are walking above the filled voids of rooms or tombs. But after a little while we come to an open area or plaza.

“One archaeologist claimed to discern an Inca palace here, or at least a prominent Inca style building to project power,” I comment, “and he saw this space as an Inca cancha. From Google Earth you can actually see the layout of one large building with multiple rooms behind the cancha, which must be this.”

Before us is a curious passageway roofed with great slabs of stone, like a private entrance way. But the passage is blocked and we both feel an unease at walking through these empty ruins. We quickly head back to the road.

I have one last thing to show Suyana. Close by the new road, which had cut through the edge of the town, there is a small room, its walls well made of flat stones faced with adobe. There is a small shelf or niche in one wall. Close to the niche is the leg bone of a llama, built into the wall, its rounded knee joint sticking out like a coat peg.

“I noticed this on my first visit, and I talked to a few people. Many of the ruined towns in this valley, perhaps all, have these. At least nine sites between the coast and upriver, every five kilometres. As far as I can see, these llama leg coat-hooks are not found anywhere else.”

“That suggests a cultural continuity for those sites,” says Suyana.

“One of the higher settlements, at Checas, appears to be a ritual funeral centre with signs of slaughtering and burning of camelids. Of course llamas were important everywhere, but they appear to have had added significance in this particular valley.”

Suyana thought about this.

“If it was a major route to the highlands, with teams of llamas going up and down every day, I expect the people of the valley might make a living servicing the caravans. Providing fodder, shelter, maybe fresh animals, and taking in lame or sick animals.”

“There is a network of trails here,” I tell her. “From this town they lead south-east to the next valley, to Omas. There are also connections to valleys to the north, to Chichacara, to Chilca and to the Lurin valley. Every year the people of Chilca walk over the hills to Calango, carrying an effigy. They meet the people of Calango in the middle by a sacred cave. There was a much more active transport network in the past, it seems.”

“There were a lot more people,” Suyana observes, “before the country was destroyed by the diseases and the wars the spanish brought. And of course travelling over these hills with llamas is easy enough. But cars can not follow them. The modern roads are few, and mostly on the coast and in the valleys.”

***************************************************************************

We are just 30 minutes away from the stones now.

I ask Suyana if she knows why they built the roads on these steep hillsides, rather than along the valley.

“In these coastal valleys farming land is scarce, just a narrow strip by the river that they can irrigate. They did not want to build a road across good farmland. You will notice that the old settlements too, the ruins, are all above the canals, outside the farming zone.”

“It seems amazing that they could build a stable pathway with unmortared stones on such precipitous slopes.”

“They are amazing to you. But you come from Europe, one of the flattest regions of the world. Your highest “mountain” in England is less than 1000 metres. There are hills on the coast in Lima higher than that.”

“It is a big adventure to go and climb Snowdon or Scafell.”

“The people of these highlands climb mountains every day, they build terraces to hold the soil and canals to channel water. Their animals graze there, and they must follow them. These roads that astound you are routine to a highlander.”

“We are not in the highlands here.”

“No, but I imagine they brought people from the sierra to build these roads.”

*************************************************************

Descending from the rock at Retama we can see that the river is still low enough to cross. As October approaches, the waters will swell with snow melt and early rains. But the water barely covers our ankles, as we walk from stone to stone to a strand. The further side is deeper, and the farmer has constructed a whippy traverse of branches laid between rocks. I tiptoe across, whilst Suyana prefers to go knee deep and walk beside the bridge.

“There are more than a hundred llama figures, spread across fifteen stones, ” I explain to Suyana. “There are fourteen lines of llamas, three or four, walking nose to tail. Several are led by a human figure. They are drawn in different styles, No two are the same. Some are drawn fully shaped, with four legs, and others are highly stylised, just a few straight lines, drawn in profile. What I am wondering is why were they drawn and, dare I ask, what do they mean?”

For the next hour or two we walk among the stones, looking at the images, taking photographs and making notes. Then we rest on a great metre wide wall of packed stones and share some cheese and bread.

“So, any thoughts on what these motifs mean?”

“I cannot tell you what they mean. I doubt that anyone can do that, other than the people that drew them. But I see many images that I have seen before in Peruvian art. One of my family, Jesus Ruiz, compiled a book of these images, of the Andino iconography.”

“You are thinking of the stylised fish, the pair of felines?”

“And also some of the birds, the mice. Those are classic Late Horizon motifs, from 500 to 1000 years ago, that were used along the length of the central coast from Chimu to Chincha. They are readily identifiable and can be drawn with a few simple lines on ceramics, woven in textiles, or sculpted in a clay frieze.”

“A sort of mass produced imagery.”

“And they spread widely so that we can not tie them to a particular time or place. The stylised, rectilinear llamas I would group with those.”

“Are they llamas? Why not alpaca, vicuña?”

“Those that are shown in lines, with a human figure, you will notice that the llama is taller than the person. Adult llamas are about 170 or 180 cm, taller than the average Andean herder. Alpaca are smaller, and guanaco and vicuña are wild animals. So yes, they are llamas.”

“And what about the four-legged llamas?”

“The llamas drawn with 6 or 7 straight lines, in the stylised manner, are all in lines of several llamas, like a caravan. Some caravans are less stylised, but still show the llamas in profile. On the other hand, the four legged creatures are not in groups. There is one pair, perhaps, and the rest are single.”

“Could they be wild animals?”

“Possibly. Certainly the people that drew them were from a different artistic tradition. They were not fixated on caravans. People in the highlands breed llamas for meat, for fibre, for example. And they might hunt guanaco, even vicuña.”

“So the four legged creatures could have been drawn earlier, or by a different people from the highlands, or even both?”

“The lines of llamas are drawn at ground level, or along shelves of the rock, as if they are walking on trails. The guanaco, if we can call them that, are mostly drawn up on the shoulder of the rock. So I would say they are wild mountain animals.”

“And the people that drew them came from the highlands?”

“That is certainly plausible. Or they were hunters. Guanaco roamed free near the coast too, before the spanish came.”

*******************************************************************

We wade back across the river, holding onto the lashed branches laid flat between rocks of the temporary bridge, feeling for secure footings between the rounded boulders. The water is cold and the current is fast. But the sun is strong. It is late afternoon and though it is dipping to the west, it still stands high above the mountains.

Crossing the strand of water worn rocks and grey sand to reach the road, we stop to look back at the orchards. The rocks stand tall amongst the apple trees. How much more impressive would they be, I wonder, if this was a sacred site designed to inspire awe? Were these stones surrounded by patios of smooth clay, covered with river sand? Did dreadlocked priests lead supplicants from rock to rock along ritual walkways, with rivulets of water running in channels between them? Did sacred llamas graze here, with bright red tassels hanging from their ears?

We are just in time to catch the bus as it heads back down the valley, the daily link between the middle and upper valley and the coast. Today these people are mostly heading down to buy farm tools and building materials, and to sell their produce, whilst others go up valley to visit relatives. Why, I wonder, would they have been travelling up and down the valley 1000 years ago?

*****************************************************************************

Back in Mala we leave our bags at the hotel which overlooks the town square, and walk through the early evening streets of the town. The main road stretches 300 metres, from the old square to the coastal highway.

There are roadside stalls selling fried chicken, movies on DVD, anticuchos, deep fried donuts, and bottles of fermented chicha. The market is shut but the funeral parlours, opticians, stationery stores and hairdressers are still busy. Three wheeled moto-taxis whine alarmingly down the street.

We find a bar with wifi, the only one in town. It is decorated in dark wood and mirrors and the back room has an empty fish tank and loud music. The food includes a variety of burgers and pizzas. The proprietor is welcoming and the Venezuelan waitress is cheerful and friendly. And they serve a Peruvian rarity, draught beer.

“It has been great to share your ideas on this,” I tell Suyana, “But I still feel a long way from understanding the people behind these drawings.”

“There is no simple answer. The Inca state incorporated many different peoples, with different languages and customs. The city of Cusco was a living demonstration of this diversity. They settled people from all the different parts of the empire in different districts, and each displayed their own headwear or hair style. When you ask “what did this mean?” you have to add “and to who?”

“To who? To the people who visited this space, which certainly means the inhabitants of the Mala valley, and perhaps others from further afield, to the north and south, from the coast to the highlands. I am trying to understand what were their values, their ideas? What did a llama or flowing water or maize, birds and spirals, what did all these mean to them? All I have to go on is the stories of Spanish chroniclers, and various interpretations of textiles, ceramics, and legends.”

“You can do better than that, if you want to understand what these people thought and felt,” Suyana answered. “The people themselves wrote it down in the Huarochiri Manuscript. Here, I brought you a copy.”

**************************************************************************************

8th December 2016. Education Minister Jaime Saavedra is called before Congress to answer questioning about his record, prior to a vote on whether to call for his removal.

The night before, Hector Becerril revealed that false email and Whatsapp accounts had been set up in the name of the Educational Infrastructure Programme to mislead regional governors and solicit funds from them.

His information came from an official Education Ministry announcement which also said that they had been alerting regional governors and mayors to the problem for over a year and had recently issued a denuncia penal for those responsible.

One of Jaime Saavedra’s achievements has been the introduction of the PISA test to Peru.

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a triennial international survey run by the OECD which aims to evaluate education systems worldwide by testing the skills and knowledge of 15-year-old students from all member countries on the same scale. 72 countries and economies took part in 2015.

Peru joined PISA in 2009 and in a comparison with 65 countries was third from the bottom in reading, third from bottom in mathematics, and and second from bottom, above Kyrgyzstan, in science.

Its scores were 370, 365 and 369 respectively, against OECD averages of 493, 496 and 501.

To put this in context, many countries with tterrible levels of education do not submit themselves to assessment by PISA. So Peru has simply the worst educational standards worldwide, of those countries that are brave enough to submit to measurement.

In 2012, Peru had the worst PISA scores of the 65 countries. The Peru scores in reading maths and science (with OECD mean scores in brackets) were 384 (496), 368 (494), 373 (501).

In 2015 Peru was placed above Lebanon, Tunisia, Kosovo, Macedonia and the Dominican Republic, with scores of 398 in reading (mean 493), 387 in maths (mean 490) and 397 in science (OECD mean 493). There had been a clear improvement, although from a low base.

In the proceedings in Congress to oust Jaime Saavedra, Fuerza Popular member Segundo Tapia says the only reason that Peru had risen in the PISA rankings was because five new African countries had joined the international tests. These countries, he continues, are Algeria, Macedonia, Panama, Georgia and Moldavia. Another congresista says Jaime Saavedra has paid the OECD to give better results. A third Fuerza Popular member, who sits on the Congressional Education Committee, raises his concern about “a disease called Alzheimer’s which is caused by excessive studying and reading”.

22nd December 2016. The Congress votes to oust Jaime Saavedra with the 70 votes from Fuerza Popular and 10 from Apra, plus three others.

“The Economist” calls the move by Fuerza Popular “a small act of national suicide by Peru”.

***************************************************

March 7th 2017. Ursula Letona and Alejandra Aramayo of Fuerza Popular propose the introduction of a law that those condemned or investigated for crimes of corruption can not occupy high positions in the national media.

Alejandra Aramayo is from Puno but was elected a Congresista for the first time in 2016, representing Fuerza Popular in Arequipa. She has been accused by several Puno businesses of running an extortion racket with her father Jorge Aramayo, threatening bad publicity through their TV channel if they did not pay up.

16th March 2017. It is announced that Jaime Saavedra, the former Peru Minister of Education ousted by a Congress vote, has been appointed the next head of Global Education Practice at the World Bank.

22nd May 2017. Martin Vizcarra, Vice-President and Minister of Transport and Communications, resigns after being called before Congress to account for the promotion of a new airport in Chincheros, near Cuzco.

21 June 2017. Alfredo Thorne, Minister of the Economy and Finance, another Minister of the highest academic and professional credentials, fails to convince Congress to back him with a vote of confidence and resigns.

8th September 2017. Marilu Martens, Minister of Education who replaced Jaime Saavedra, is called before Congress to answer questions about the teacher’s strike, which is now over. Spokespeople for Fuerza Popular have said they have already decided to support a motion to censure her, which will force her dismissal if passed.

13th September 2017. A motion to censure Marilu Martens is passed. In response, the President calls for a vote of confidence. If Congress opposes a motion of confidence against the Executive twice, the President can dissolve Congress and call new elections.

15th September 2017. The Executive fails the motion of confidence and the President has to appoint a new cabinet.